The Fake China Threat and Its Very Real Dangerby Joseph Solis-MullenLibertarian Institute, 2023; vii + 145 pp.It’s often claimed that China, aspiring to world hegemony, plans to wage war against the United States. Democrats and Republicans alike warn of an impending war. Joseph Solis-Mullen, a libertarian who often writes for antiwar.com and knows a great deal about China (although he claims he is no Sinologist), dissents. In his view, China poses no threat to America. The difficulty in the relations between the two countries rather stems from the fact that China has built up sufficient military capacity to have a good chance of defeating an American assault aimed at defending Taiwan, which is hardly evidence of Chinese aggression. Solis-Mullen maintains that the

Topics:

David Gordon considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

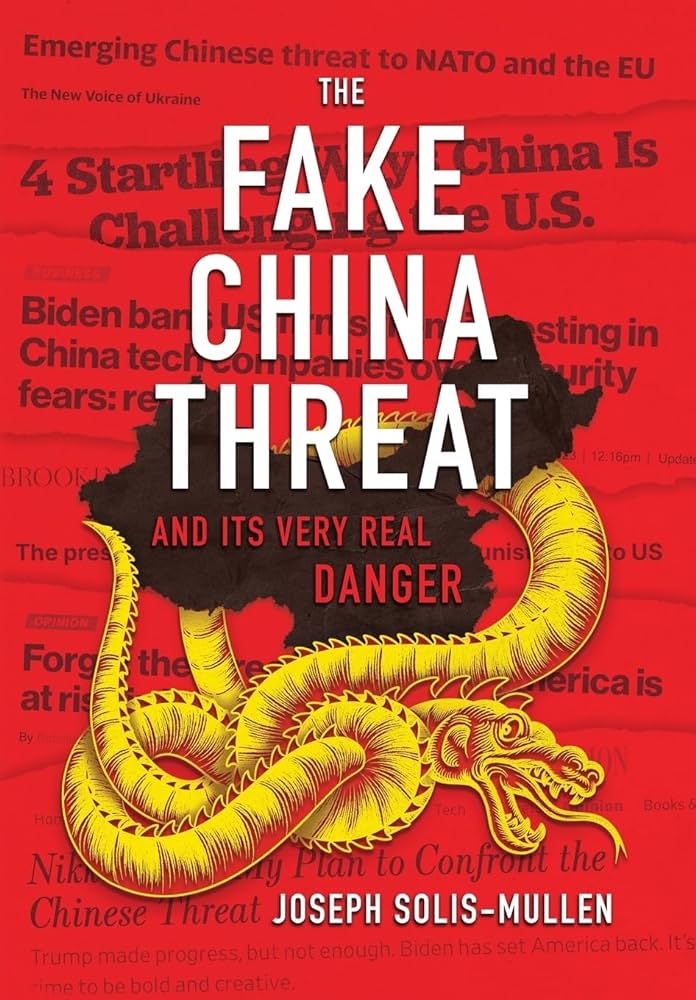

The Fake China Threat and Its Very Real Danger

by Joseph Solis-Mullen

Libertarian Institute, 2023; vii + 145 pp.

It’s often claimed that China, aspiring to world hegemony, plans to wage war against the United States. Democrats and Republicans alike warn of an impending war. Joseph Solis-Mullen, a libertarian who often writes for antiwar.com and knows a great deal about China (although he claims he is no Sinologist), dissents. In his view, China poses no threat to America. The difficulty in the relations between the two countries rather stems from the fact that China has built up sufficient military capacity to have a good chance of defeating an American assault aimed at defending Taiwan, which is hardly evidence of Chinese aggression. Solis-Mullen maintains that the United States ought to withdraw from Taiwan, which in his view is clearly an area properly under Chinese sovereignty. Doing so, he thinks, would greatly improve the chances of good relations between the two countries.

Solis-Mullen’s argument against an aggressive policy toward China does not depend on China’s intentions. No matter how hostile China may be, he thinks, it lacks the capacity to invade us.

Solis-Mullen’s argument against an aggressive policy toward China does not depend on China’s intentions. No matter how hostile China may be, he thinks, it lacks the capacity to invade us.

Solis-Mullen adduces a host of difficulties that would make it difficult for China to invade, including America’s geography and China’s continuing demographic collapse, resource constraints, discontented minority groups and hostile neighbors. Why, then, does the U.S. government endeavor to convince people that the danger of invasion is substantial? Solis-Mullen’s answer is that it is in their interest to do so. It is a way for the state to convince us to surrender our

liberties and enhance its own power.

He calls attention to a remark by William F. Buckley Jr., a CIA operative who claimed to be a libertarian:

“Deeming Soviet Power to be a menace to American Freedom ... ‘we shall have to rearrange, sensibly, our battle plans; and this means that we have got to accept Big Government for the duration [of the Cold War contest] ... for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged ... except through the instrument of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores.’

... “‘Ideally,’ Buckley wrote, ... ‘the Republican Party Platform should acknowledge a domestic enemy, the state.’” But, in his words, such ‘idealism’ must be set aside in the name of national security.”

In brief, those in control of the state tell us that we must give up freedom in order to defend freedom. Citing Robert Higgs and Randolph Bourne, Solis-Mullen says:

“This relationship between war, the preparation for war, and the loss of individual freedom to government, is so obvious one can find any number of such quotations to this effect — even if this common sense wisdom, in the day-today bustle of life and the thousand decisions that entails, often gets lost, shuffled into the background, provisions violating our most fundamental rights stuffed into the footnotes of bills thousands of pages long and passed without ever having been read.”

In order to grasp Solis-Mullen’s argument, it is essential to understand a fundamental assumption of his that Rothbardians will find congenial. Americans have a vital defense interest only in protecting our own borders from invasion. We may deplore what happens elsewhere, but it is not our concern to try to remedy problems abroad. He says about the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur minority:

“Are Uyghurs being discriminated against? Maybe. Maybe even probably. But should that serve as the basis of policy toward Beijing? Assuredly not. Such discrimination is hardly unique, nor is having an abysmal human rights record. This does not prevent the likes of Egypt or a host of other authoritarian states from sitting comfortably on the U.S.’s payroll. It is obvious to everybody, allies, frenemies, and foes alike, why Washington has decided to make the Uyghurs an issue: it serves their interests.”

Solis-Mullen’s conclusion that the United States should not get involved in what does not directly threaten us is right, but there is a problem with the argument just presented. It rests on the premise that if one is concerned with human rights violations, one must either act against all such violations. Why can’t one be concerned with some violations and not others, depending on one’s interests? Being concerned with some violations does not logically require one to be concerned with others.

Solis-Mullen’s presentation of U.S.-China relations is informative. He stresses that the Chinese have often responded to American provocations, and readers will profit from his expert account. I disagree with him, though, in one area. He says:

“Content to let the warring Japanese and Chinese bleed one another throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, it wasn’t until near the conclusion of the U.S. Pacific theater campaign against the Japanese that real aid started to flow to the corrupt, ineffectual, nominally Republican forces. Though the aid would continue in the years following the Japanese surrender, it was clear, particularly to George Marshall, who visited China to encourage a reconciliation between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CCP, that good money was being thrown after bad.”

To the contrary, Anthony Kubek’s 1963 “How the Far East Was Lost” makes a good case that much of the so-called aid to Chiang Kai-shek was designed to destroy his monetary system and that Marshall had the wool pulled over his eyes by advisers who were Communist sympathizers. Readers should bear in mind that the defects of the KMT shouldn’t lead us to forget the defects of the KMT.

Despite a few points of disagreement, I highly recommend “The Fake China Threat and Its Very Real Danger.” Like Murray Rothbard, Solis- Mullen is fully aware of the dangers posed by court intellectuals, who defend positions that will give them power and wealth. He says about them, “Regarding conflicts of interest, it is easy for anyone concerned to discover who pays the people writing these books [claiming that China threatens the United States]. Hardly the product of merely concerned citizens or honestly interested academics, almost invariably they are produced by people with a direct financial or career interest in great power conflict, specifically with China.”

Tags: Featured,newsletter