The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the world’s largest free trade area by the number of countries. It is the most ambitious and, given demographic trends, the most promising free trade project on earth. The AfCFTA matters very much to Africa’s economies separately and to the continent’s collaborative and integrated economic development. If successful, it also carries significant implications for the global economy. As such, the AfCFTA matters. Not just for Africans but for everyone. The AfCFTA was established in 2018, and trading under the agreement officially started on January 1, 2021. I say officially because, oddly, no trade has taken place under the agreement to date. Over a year later. Although with governments almost everything takes

Topics:

Manuel Tacanho considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the world’s largest free trade area by the number of countries. It is the most ambitious and, given demographic trends, the most promising free trade project on earth. The AfCFTA matters very much to Africa’s economies separately and to the continent’s collaborative and integrated economic development. If successful, it also carries significant implications for the global economy. As such, the AfCFTA matters. Not just for Africans but for everyone.

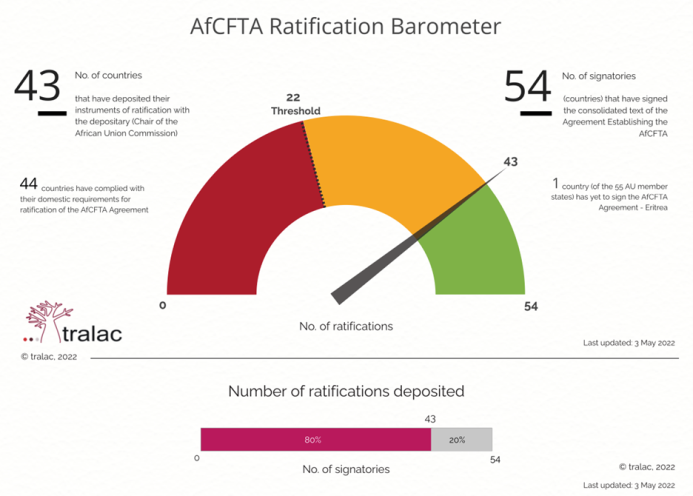

| The AfCFTA was established in 2018, and trading under the agreement officially started on January 1, 2021. I say officially because, oddly, no trade has taken place under the agreement to date. Over a year later.

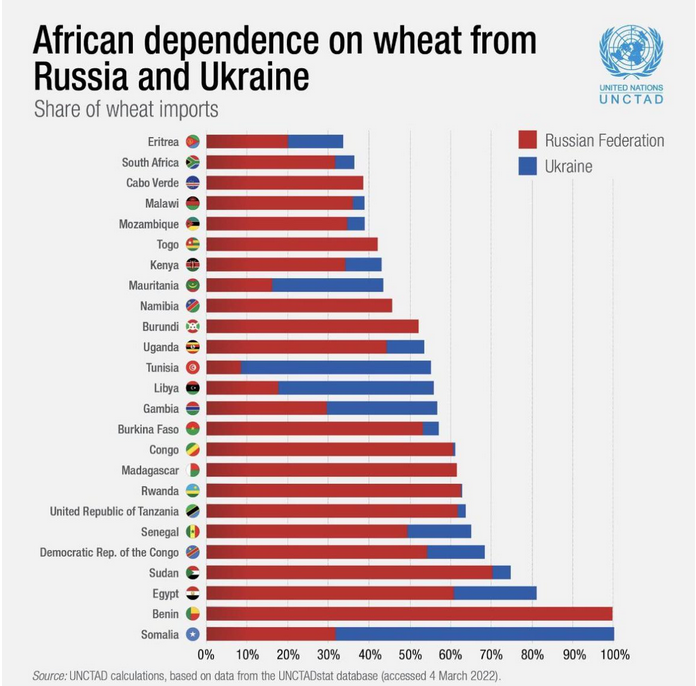

Although with governments almost everything takes longer and costs more than otherwise, it is confusing, unsettling, and perhaps also embarrassing that sixteen months since the start of trading, no trade has taken place under the AfCFTA. Especially considering that to lift millions out of poverty and spur real economic development across the continent, Africans must freely trade with one another on a larger scale. So why hasn’t trading taken off under the AfCFTA? No, it is not due to covid restrictions, the Russia-Ukraine war, or other external factors. The reason postcolonial African societies barely trade with one another is philosophical. At independence, instead of dismantling the colonial mercantilist barriers to restore free and borderless trade between Africans, African leaders, driven by socialist thinking, doubled down on colonial statist and protectionist regimes and, in most cases, made then even more statist and repressive. That is essentially why intra-African trade has been dismally low. |

Africa’s Heavily Statist Economic Systems

Contrary to entrenched views, today’s economies from the first world to the third are not free-market capitalist. Even the United States, the stronghold of “capitalism,” is not a free-market economy. Instead, we, humanity, live under statist economic systems of varying severity.

As explained in this article, some of the most statist (i.e., cruel and oppressive) systems are found in Africa. The vast majority of African countries are consistently ranked as mostly unfree and repressed in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom. Two refreshing exceptions are Mauritius, which ranks as mostly free, and Botswana, which stands out for its relative economic success.

In this context of repressive statist economic systems, it should not be a surprise that, sixteen months later, no trade has taken place under the AfCFTA. Said another way, trading has not yet taken place due to the suffocating degree of economic and monetary repression imposed on Africans by African governments.

African politicians and bureaucrats, most of whom hold statist/socialist views, are still reluctant to dismantle the many artificial barriers that repress trade among Africans. The paradox here is that the very politicians who ratified the agreement to establish a single African market are the same politicians hesitating to dismantle colonial and postcolonial artificial barriers that prevent Africans from trading freely. It will take boldness and a tectonic shift in economic thinking for intra-African trade to take off and for the AfCFTA to succeed: African politicians will have to remove the many artificial economic and monetary barriers in place.

Yes, the existence of the AfCFTA is clear and indeed remarkable proof of African leaders’ commitment to creating a single African market. But how free or unfree will the market be? I contend it must be genuinely free.

Although the AfCFTA is a decisive step toward free trade within Africa, its success is not guaranteed due to the statist/socialist economic thinking among African decision-makers and the prevalence of anti–free market, anti–free trade, and anti–free enterprise beliefs among the public.

Now, the AfCFTA Secretariat could hire a major consulting firm to analyze why trade has still not taken place. The consulting firm would, of course, come up with a pile of graphs and numbers explaining the many reasons why such is. However, the fundamental reason is philosophical and hides in plain sight.

The AfCFTA Can Be Approached in Two Ways

African political leaders can approach the AfCFTA in one of two ways: the market way or the statist way.

In the statist way, governments play the leading role in centrally controlling, commanding, and regulating economic activity (i.e., people’s lives). This has been the approach in Africa since “independence,” which, evidently, failed to create free and prosperous African societies.

The market way is the natural economic system. Individuals existed long before government or the state emerged. Human life, human action (rational and purposeful), human cooperation, property ownership, and therefore free markets, free trade, and free enterprise long predate the state and all forms of government. With the market approach, African leaders would, at last, let Africans live, move, produce, innovate, and trade freely across the AfCFTA.

In contrast, the statist way would continue to repress and thus severely undermine the AfCFTA’s full potential. Politicians and bureaucrats would continue to hold power over the economy (i.e., people’s lives). Consequently, corruption, cronyism, tyranny, injustice, rent seeking, embezzling, favoritism, mass unemployment, rampant inflation, crippling debt, burdensome taxation, and widespread poverty, to name a few problems, would likely continue as they have over the last fifty years. More tragically, Africa’s unprecedented demographic dividend and youthful entrepreneurial energy would remain largely repressed and thus wasted, as it is today.

The market way is the only way to generate broad-based, decentralized, and enduring economic development. The free market is the only sustainable economic system. It is also the only system that ensures Africa’s demographic dividend becomes a great blessing and not a great curse. In other words, the market-driven approach is the only way to ensure the AfCFTA’s full potential is realized. There is no third way. An economic system can either be driven by the market or the state.

Africans Must Trade Freely Again

Government-managed free trade is not free trade. The AfCFTA should be about actual free trade. A single free African market.

Forbes Africa asks: “Will the AfCFTA Be the Heartbeat of the Global Economy?”

The AfCFTA does have the potential to become the heartbeat of the global economy. But African decision-makers must necessarily abandon their deep-seated statist and socialist economic views and embrace free markets, free trade, and free enterprise.

More importantly, African leaders must embrace Africa’s economic heritage of free markets, free trade, and free enterprise because such is the only way to recreate free and borderless African trade, which would liberate the continent from its pernicious and pervasive colonial legacies, as elucidated by Dr. Steve Davies in Restoring Trade in Africa: Liberating the Continent from the Colonial Legacy.

In “The Humanity of Trade,” Frank Chodorov clarifies:

Let us test the claims of “protectionists” with an experiment in logic. If a people prosper by the amount of foreign goods they are not permitted to have, then a complete embargo, rather than a restriction, would do them the most good. Continuing that line of reasoning, would it not be better all around if each community were hermetically sealed off from its neighbor, like Philadelphia from New York? Better still, would not every household have more on its table if it were compelled to live on its own production? Silly as this reductio ad absurdum is, it is no sillier than the “protectionist” argument that a nation is enriched by the amount of foreign goods it keeps out of its market, or the “balance of trade” argument that a nation prospers by the excess of its exports over imports.

Indeed, there are no cogent arguments protectionists can use to justify the economic balkanization within Africa and the continuation of the many tariff, nontariff, and other artificial restrictions that prevent Africans from trading freely.

Most African societies are essentially at the same level of economic development and socioeconomic precarity. To maintain the prevailing artificial barriers to trade among Africans, or to remove them only partially, is as nonsensical as South Carolinians feeling economically threatened by North Carolinians and agitating for trade barriers.

In his article “Could the AfCFTA Recreate Lost African Trade Networks?,” Alexander Jelloian notes:

Colonialism caused an increase in protectionist trade policies as European powers partitioned Africa without paying sufficient attention to social, economic, or geographic factors. Controls by the colonial authorities restructured economic life away from the natural trade relations that had existed for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. In most states, the situation did not improve after independence, as many new African leaders pursued state-led development and hoped that import substitution would spur domestic manufacturing. Industrialisation never occurred in any substantial way in most of the continent. Post-independence governments that pursued African socialism have usually kept high tariffs and border controls to this day, which continue to stifle economic growth.

Conclusion

To succeed, the AfCFTA must be about actual free trade and establishing a free single African market. Government-managed “free trade” is not free trade.

Approaching the AfCFTA with today’s heavily statist economic thinking is a recipe for the complete or partial failure of the AfCFTA, the world’s most ambitious and most promising free trade project. Because the AfCFTA matters very much for reasons that go beyond free trade, ensuring its success is vital.

Even though it is challenging to imagine African governments relinquishing the repressive control and commanding power they have amassed over the lives of Africans since independence, it is, nonetheless, vital that African leaders abandon imported statist concepts and genuinely embrace Africa’s economic heritage of free markets, free trade, and free enterprise if the AfCFTA is to succeed in delivering integrated, decentralized, broad-based, and enduring continental economic development.

Present and future African leaders must remove all—yes, all—artificial restrictions that suppress, repress, and otherwise hinder the free production, exchange, and consumption of goods and services within Africa.

Tags: Featured,newsletter