Anyone using the internet is being watched, and possibly manipulated, via a trail of digital breadcrumbs known as metadata. Two Swiss companies, one backed by former United States military whistleblower Chelsea Manning, are setting up smokescreens to confuse prying eyes and protect web users from big tech companies and government surveillance. Nym Technologies and HOPR employ mix networks (mixnet) to churn together the metadata that people leave behind when they surf the internet, making it impossible to link the scrambled digital footprints to any individual. They are part of a small band of international companies, such as Orchid and xxnetwork (founded by cryptographer David Chaum who first introduced the mixnet concept in 1981) who are attempting to fight back

Topics:

Matthew Allen considers the following as important: 3.) Swissinfo Business and Economy, 3) Swiss Markets and News, Featured, Law and order, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Anyone using the internet is being watched, and possibly manipulated, via a trail of digital breadcrumbs known as metadata. Two Swiss companies, one backed by former United States military whistleblower Chelsea Manning, are setting up smokescreens to confuse prying eyes and protect web users from big tech companies and government surveillance.

Nym Technologies and HOPR employ mix networks (mixnet) to churn together the metadata that people leave behind when they surf the internet, making it impossible to link the scrambled digital footprints to any individual.

They are part of a small band of international companies, such as Orchid and xxnetwork (founded by cryptographer David Chaum who first introduced the mixnet concept in 1981) who are attempting to fight back against the erosion of privacy online.

“Being constantly surveilled is exhausting people. They are being observed every single second, with every single click, and they don’t know where that information is going or how it’s being used. That is starting to have a long-term mental health impact on people,” Chelsea Manning, who is advising Nym Technologies, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

More than a decade ago, Manning – who was then serving in the United States military as Private Bradley Manning – leaked sensitive documents on civilian deaths during the Iraq war and the ill treatment of Guantanamo Bay detainees. She now campaigns against data surveillance by governments and big corporations by advocating greater online privacy for individuals.

“People are aware of their privacy being violated but they have an expectation that someone else will come and fix this problem – either the government or a civil rights organisation or a supranational agency like the European Union. It hasn’t played out that way,” she says.

Who you speak to and when

Metadata is sometimes likened to exhaust fumes left in the trail of online activity, social media interactions and by using smartphones. It might not reveal the content of communication, but it can be pieced together to determine who was contacted, how often, for how long and where each party was located during the exchange.

Powerful machine learning tools use metadata to build up surprisingly accurate pictures of individuals, their preferences, personality and movements, according to researchers, including Stanford University.

This offers opportunities to reveal private lives, target advertising towards consumers and surreptitiously manipulate everyday behaviour, such as voting. The Covid-19 pandemic has only increased the amount of time people spend online for tasks, such as business meetings.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has also brought into sharp focus the issue of governments controlling information and using it to advance their own arguments or to attack dissenters.

Both Nym and HOPR believe that technology is a better way of solving the problem than waiting for regulators to provide protection.

“The goal is to provide technology that empowers the individual. We need resilient systems that allow us to use the digital world without Facebook and Google harvesting data about us,” said HOPR founder Sebastian Bürgel.

Swarm effect

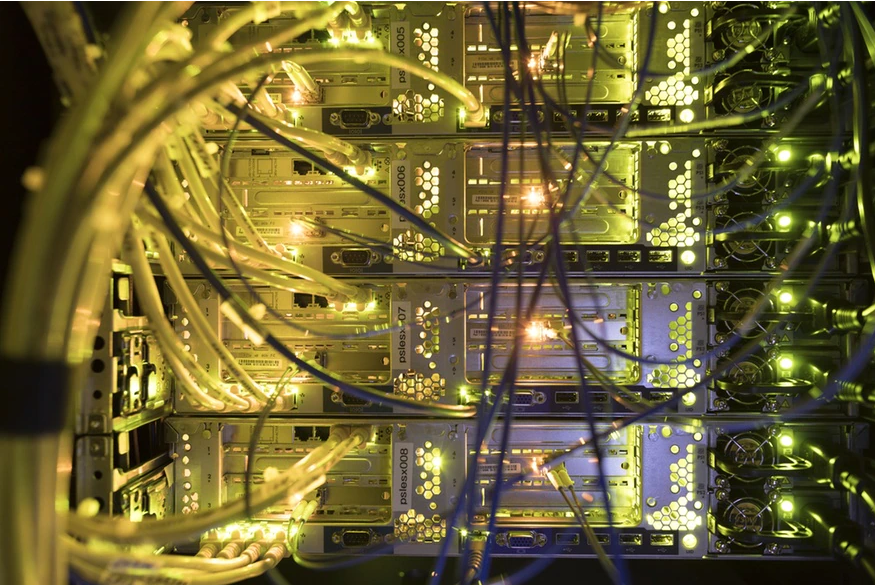

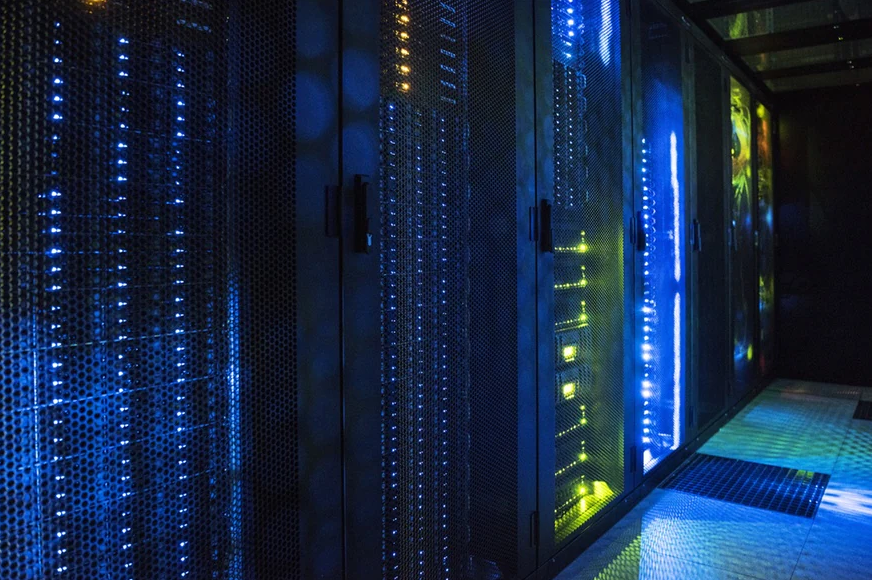

To achieve this, both systems employ the same principle of decentralisation that underpins blockchains and bitcoin. This involves a network of computers that are independently operated but are at the same time interconnected and cooperate to transmit data. The theory is that such a swarm is more trustworthy than a single corporate entity that puts its own commercial interests ahead of users.

To persuade people to get involved as mixers of data, Nym and HOPR have created an incentive system that rewards such activities with digital tokens. These tokens are also used by people who want to pay for the services of each system.

When fully up and running in the coming months, the mixnet systems could host a wide range of use cases – from decentralised finance, to sending personal data and hosting digital chat rooms. HOPR is in talks with a medical technology company that is developing devices to send alerts if vulnerable patients take a fall or whose health suddenly deteriorates, whilst keeping their data secure.

While individuals may welcome technology that protects their privacy, governments and law enforcement agencies see potential risks. Earlier this year, the British National Crime Agency expressed concern that end-to-end encryption being introduced by social media companies will inhibit efforts to detect criminals. NCA director Rob Jones said that “this capability risks turning the lights out for law enforcement worldwide”.

Irritating pop-ups

Regulators in some countries, notably the US, have cracked down on cryptocurrency mixers, or “tumblers”, declaring the most brazen attempts to disguise trails of digital money as illegal.

Harry Halpin, co-founder and CEO of Nym, rejects the argument that mixnets are a paradise for criminals. “Privacy is not about hiding from everyone; it’s about selectively disclosing the information you want to reveal,” he said. “Regulation has not led to the end of surveillance. It has just led to irritating pop-up windows and a few relatively minor fines.”

Halpin also points out that Nym receives funding from the European Commission’s Next Generation Internet initiative for building a more inclusive web and that the Swiss state-owned telecoms provider Swisscom has signed up to help operate the system.

The battle for digital privacy is being lost at an alarming rate, he contends. “You need to fight back with technology, using software that makes surveillance impossible, or at least being surveilled is not the default option on the internet.”

Technology is already providing privacy solutions. In Switzerland, ProtonMail and Threema encrypt email and messaging traffic. The Brave internet browser blocks online advertisers while The Onion Router (Tor) preserves anonymity by directing traffic though relays located in different layers of the system.

But Nym and HOPR claim that their mixnet technology goes further than privacy rivals by specifically targeting metadata and by introducing operating models that are less cumbersome and time intensive than competing systems.

Blockchain insecurities

And while blockchains have a reputation for anonymity, Sebastian Bürgel warns that the decentralised databases potentially present even greater privacy risks than the internet.

Blockchains function by broadcasting transactions to the entire network of users but not the identity of individuals.

People are increasingly using specialised websites to check that their transaction has been completed or are going online to access services such as exchanges. Each time they do so, they leave metadata trails such as their IP address.

“This information is so far only available to service providers. But there is a danger that your IP address could be leaked to the entire network and used to find out where a transaction originates from,” says Bürgel.

Mixing metadata to make it untraceable is, according to Bürgel, the only way to ensure that this does not become a problem.

Tags: Featured,Law and order,newsletter