Most of the big Swiss textile machinery companies have local production in China and only export high-end components from Switzerland. © Keystone / Gaetan Bally Amid allegations of forced labour involving Uyghur and other minorities in the garment supply chain, the Swiss textile machinery sector faces thorny questions about its ties to and reliance on China. My specialty is telling stories, and decoding what happens in Switzerland and the world from accumulated data and statistics. An expatriate in Switzerland for several years, I have also worked as a multimedia journalist for the Swiss national broadcaster. More about the author | French Department In 2014, the same year the Swiss-China free trade deal went into force, a group of industry colleagues

Topics:

Swissinfo considers the following as important: 3) Swiss Markets and News, 3.) Swissinfo Business and Economy, Business, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

RIA Team writes The Importance of Emergency Funds in Retirement Planning

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Gesetzesvorschlag in Arizona: Wird Bitcoin bald zur Staatsreserve?

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes So bewegen sich Bitcoin & Co. heute

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Aktueller Marktbericht zu Bitcoin & Co.

Most of the big Swiss textile machinery companies have local production in China and only export high-end components from Switzerland. © Keystone / Gaetan Bally

Amid allegations of forced labour involving Uyghur and other minorities in the garment supply chain, the Swiss textile machinery sector faces thorny questions about its ties to and reliance on China.

In 2014, the same year the Swiss-China free trade deal went into force, a group of industry colleagues including a representative of the Swiss firm Uster Technologies visitedExternal link cotton gins and spinning mills in Xinjiang, Western China. The trip included a visit with the then-Deputy Commander of the Xinjiang Construction and Production Corps, also known as XPCC.

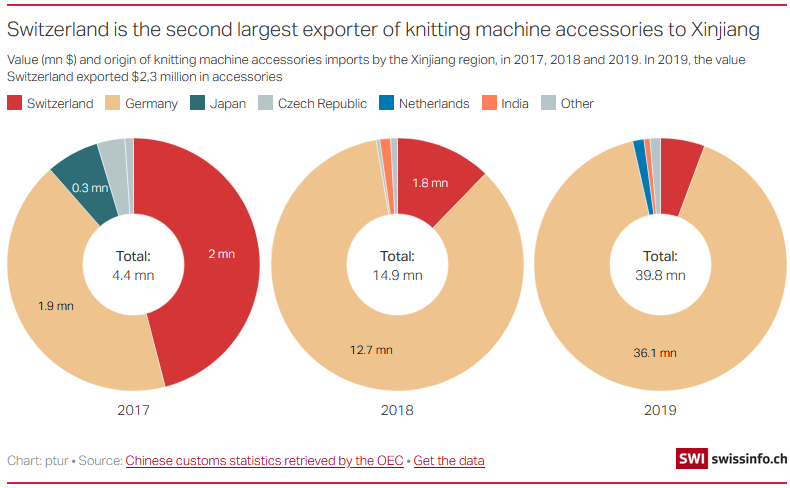

Over the next several years, the Swiss textile machinery industry would benefit from the expansion of textile production in Xinjiang. By 2017, Switzerland was the largest exporter of knitting accessories such as spindles and spare parts to Xinjiang, according to customs data.

This was two years before the release of the so-called China CablesExternal link: leaked documents from within the Chinese Communist Party that revealed details about an alleged state-sponsored campaign of repression against Uyghur and other ethnic minorities in the Western region of the country, including forced labour in the textile supply chain.

US government sanctions on the XPCC and some textile manufacturers over the allegations have put the spotlight on brands like Nike and H&M, who have become entangled in a consumer backlash for expressions of concern over the situation.

Usually safely under the radar, Swiss firms like Rieter and Uster that sell textile machinery to factories in China including Xinjiang are now facing difficult questions of their own about the industry’s heavy reliance on China.

Niche market

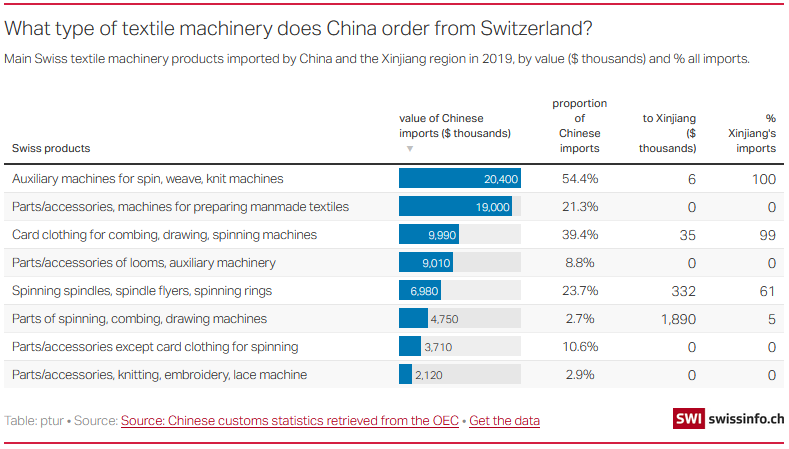

It’s difficult to know how many Swiss textile machines wind up in Xinjiang. Customs dataExternal link shows that Xinjiang imported $6.4 million (CHF6 million) worth of machines of all sorts from Switzerland in 2019, making the Alpine country the 37th-largest exporter of machinery to the region.

When it comes to textile machinery, customs data retrieved from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) shows that Xinjiang imports most of its machinery from three countries: Germany ($26.8M, 46.5%), Japan ($23.4M, 40.6%) and Italy ($7.4M, 12.8%).

Switzerland, however, is a major exporter of knitting machine accessories such as spindles, dobbies, and automatic stop motions used in big spinning, weaving or knitting machines.

Customs data shows that in 2019 knitting accessories were the second-largest Swiss export to Xinjiang after industrial printers. Over the last three years, Switzerland exported knitting machine accessories to the autonomous region worth around $2 million per year.

| Although the total value is small, China, and Xinjiang in particular, relies heavily on Switzerland for some machinery and parts.

While Germany supplied the vast majority of knitting machine accessories exports to Xinjiang in 2019 (almost 91%, accounting for $39.7M), Switzerland played a particularly big role at the height of Xinjiang’s major textile industry expansion a few years ago. In 2017, Switzerland was ahead of Germany, accounting for around half of knitting accessory exports to Xinjiang. |

What type of textile machinery does China order from Switzerland? |

| According to the Zurich-based International Textile Manufacturers Federation (ITMF), there was a massive increase in the shipment of rotor spinning machines to China, from 383,000 in 2015 to 634,000 in 2016. “The main reason was that more spinning capacity was relocated from the coastal regions to major cotton growing regions of [Western] China,” Christian Schindler from ITMF told SWI swissinfo.ch. |

Switzerland is the second largest exporter of knitting machine accessories to Xinjiang |

Subsidiaries, mergers and acquisitions

But export data only shows part of the picture. Ernesto Maurer, president of the Swiss Textile Machinery Association, noted in the association’s 75th-anniversary brochureExternal link that “through their numerous international subsidiaries, Swiss textile machine manufacturers control far more [market share] than is revealed by national customs statistics”.

This is because most of the big Swiss textile machinery companies have sales agents and subsidiaries with local production in China and only export high-end components from Switzerland.

The number of mergers and acquisitions in the industry also makes it difficult to see where production takes place. Textile machinery firm ITEMA, which is headquartered in Italy, is the result of a fusion of various brands including Swiss brand Sultex. ITEMA has production facilities in several countries including China, Switzerland and Italy. Japanese company Toyota Industries took over Uster Technologies back in 2012.

Some companies have been bought out entirely by Chinese investors and only maintain offices or research arms in Switzerland. Chinese firm Ningbo Cixing bought Swiss company Steiger in 2010, helping it become one of the biggest flat-knitting companies in the world. Another Chinese firm, Jinsheng, bought the 150-year old Saurer brand from the Oerlikon Group in 2012. In its 2017 annual report, Saurer indicated that 37% of its 4,400 employees were in China, while only 3% were in Switzerland.

That same year, SaurerExternal link set up a wholly owned subsidiary, Saurer Xinjiang, producing two million carding, roving frame, winding spinning and rotor spinning systems to “meet growing demand” as textile production expanded in the region. The factory was fully operational in 2019.

Supplier ties

Machines with origins in Switzerland, wherever they are ultimately produced, are being used in factories that have been slapped with US sanctions over allegations of forced labour. In May 2019, the Wall Street JournalExternal link reported that Xinjiang residents were forced into training programs that send workers to area factories, some of which were weaving yarn or spinning textiles for major brands.

The Chinese government has denied the allegations and defended the program as a mass training campaign aimed at lifting the ethnic group out of poverty and fighting terrorism.

According to the Lausanne-based newspaper Le TempsExternal link, the Swiss group Rieter sold 66 Ring Spinning G32 machines, used to weave cotton, to the Chinese company Huafu Top Dyed Melange Yarn in 2019. The paper reports that Swiss firm Uster also sold equipment to Huafu, which landed on the US blacklist in 2020.

Another company on the US blacklist – Hong Kong-based Esquel Group – has cotton mills in Xinjiang that use equipment from Uster. Two of the millsExternal link in Xinjiang – Changji Esquel Textile Co and Turpan Esquel Textile Co. Ltd – received a quality seal from Uster in 2019.

Esquel, which has operated in Xinjiang since 1995, has denied allegationsExternal link of forced labour and noted that a third-party audit found no evidence of it. The company states on its website that its Changji spinning mill is an “advanced state-of-the-art, highly automated factory” that only requires 45 technicians compared to a traditional mill that requires 150 employees to operate. Some of the highly automated machinery is from Swiss firm Rieter, as seen in this videoExternal link from the company.

When asked for more information, Rieter said that it doesn’t provide information about business relationships with individual customers.

Saurer’s 2019 annual report indicated that its Xinjiang factory participated in a local government scheme to increase employment among ethnic minorities, hiring 95 ethnic minority employees in its new plant.

In response to a request for more details, the company said that “the ethnic minority employees at the company’s Urumqi plant are engaged in a variety of positions and range from shop floor workers to university graduates, working in all industrial fields”.

Shelly Han from the Fair Labour Association, an NGO which was established in the US to advance labour rights protections after the sweatshop scandals in the 1990s, told SWI swissinfo.ch that she doesn’t believe every factory in Xinjiang uses forced labour. However, she adds, there is no way to prove a negative.

“We believe that companies can’t do effective due diligence in Xinjiang at all because of the extreme surveillance [by the Chinese government]. This means auditors have no freedom of movement and workers can’t speak openly,” said Han.

In December, the FLA stopped sourcing from Xinjiang because the situation “defies conventional due diligence norms” and therefore it couldn’t rule out forced labour. This marked the first time in its 20-year history that the association told companies it works with such as Adidas and Patagonia not to source from a particular country or region.

Cut and run

In this context, companies increasingly face reputational risks from any business ties to Xinjiang or to allegations of forced labour. And, the questions are unlikely to go away as recent reportsExternal link suggest workers are being forcibly transferred from Xinjiang to other provinces.

But can an industry that sells a machine that sits on a factory floor for years be held accountable to the same extent as a brand that continually buys fabric or cotton t-shirts made with alleged forced labour?

Dorothée Baumann-Pauly from the Geneva Centre on Business and Human Rights says to imagine the fallout from a picture of a Uyghur worker sitting at a machine bearing the name “Rieter” appearing on the front page of a major newspaper.

“Companies selling machinery to the region face some of the same questions as those selling technology that could be used for surveillance,” she said. “You have to figure out who you are selling to and what it is being used for.”

Han argues that machinery companies should know who they are in business with. “You may not necessarily be directly contributing to human rights abuses, but you are contributing to a system that is creating these human rights abuses. And in in the case of Xinjiang, it is a system,” said Han.

And Angela Mattli from the Swiss NGO Society for Threatened Peoples questions how seriously companies are taking the situation.

“You need to have a red line as a company. You have to expect certain information from business partners in China. And, you need to have exit clauses in your contracts,” The NGO has initiated a dialogue with the Swiss machine industry association, Swissmem, over the situation in Xinjiang.

What companies say

Swiss textile machinery companies who responded to SWI swissinfo.ch all expressed a similar message of zero tolerance for discrimination or human rights abuse.

In an emailed statement to SWI swissinfo.ch, Rieter wrote that it “rejects forced labour. This principle is anchored in the Rieter Code of Conduct,” and that in all of its business relationships, it is “committed to comply with all relevant laws and regulations”.

Saurer said it takes “great pride in ensuring that we respect the personal dignity, privacy and personal rights of our employees.

Uster Technologies wrote to SWI swissinfo.ch that they “only work with partners who treat their employees fairly and comply with applicable law,” including refraining from using forced labour and that “we have so far never directly experienced any circumstances indicating that any of our clients were acting against our code of conduct”.

The companies, however, didn’t comment on the specific allegations about Xinjiang or provide details about how they ensure suppliers or customers comply with their standards.

Florian Wettstein, a professor of business ethics at the University of St Gallen who has written about silent complicity, told SWI swissinfo.ch that companies have to consider what signal their presence sends to the outside world and if it lends legitimacy to human rights abuses.

He added though that the importance of the Chinese market means that “companies are extremely careful about what they say”.

A delicate position

The situation for Swiss companies is particularly delicate. China is Switzerland’s third-largest trading partner, and Switzerland was the first Western country to sign a free trade deal with the superpower.

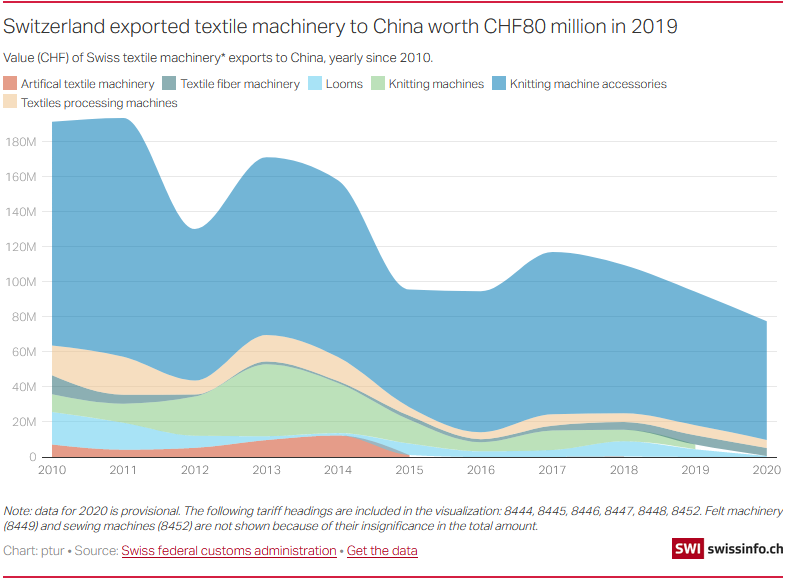

China represented about 17% of Swiss textile machinery exports in 2019 and 16% in 2020 (CHF474 million). The Chinese market is seen as key to helping the export sector weather uncertainty during the Covid-19 pandemic.

| But the industry is facing tough competition from China itself. Total exports of Swiss textile machinery have declined in the last few years as China’s own machinery sector becomes more sophisticated and Swiss companies establish more local production in China. Most textile machinery is now produced in China and by Chinese companies.

“Foreign competitors are not sleeping. They’re catching up technologically,” said Stefan Brupbacher, director of the machinery umbrella organisation Swissmem. “Barring Swiss companies from selling and servicing China as a market would give Chinese and foreign companies a big advantage over Swiss companies in a thriving market”. Chinese production not only serves the local market but many other manufacturing markets. |

Switzerland exported textile machinery to China worth CHF80 million in 2019 |

Political levers

Given the industry’s delicate tightrope walk with China, it is unlikely that companies will speak up or change their practices without some political pressure or cover. This is especially true after seeing how the Chinese government and consumers retaliated against H&M and Nike over their expressions of concerns over the situation in Xinjiang.

Schindler told SWI swissinfo.ch that “these contentious issues with regards to trade are for governments to deal with. The companies are focused on meeting customer demands”.

Rieter also wrote that it relies on the political institutions that deal with this matter. An Uster spokesperson said that “it is not up to us to set or change these regulations or to take sides in any discourse of governments”.

For its part, the Swiss government has not taken a hard line with China. Both the Swiss parliament and the government recently rejected a proposalExternal link for an import ban on goods made with forced labour which would have been similar to what is stipulated in the US Tariff Act. The European Union has also slapped sanctions on some individuals.

Brupbacher of Swissmem questions the effectiveness of boycotts and unilateral sanctions. “Trade helps foster a middle class. We’ve seen that in China, where trade has helped lift millions out of poverty.”

The Swiss economics ministry confirmed to SWI swissinfo.ch that it has been in touch with individual textile machinery companies and that it is “planning an exchange with various companies from the textile machinery industry on the human rights situation in Xinjiang” but that a date has not been set.

Two weeks ago, the Swiss government released its first-ever China strategy that noted a desire to continue human rights dialogue with China. China’s ambassador to Switzerland lashed out saying the criticism sent the wrong signals and was based on false accusations.

In a recent interview in Zurich’s Neue Zürcher Zeitung, foreign minister Ignazio Cassis said sanctions were being analysed but that Switzerland has its “own foreign policy”.

Cassis also said that he welcomed companies taking responsibility for their supply chains.

“If companies do not take responsibility, the state intervenes and regulates.”

Tags: Business,Featured,newsletter