Fueled by unprecedented quantitative easing, central bank asset purchases, and various stimulus packages, the money supply growth rate ballooned in April to an all-time high. The growth rate has never been higher, with the 1970s as the only period that comes close. It was expected that money supply growth would surge in recent months. This usually happens in the wake of the early months of a recession or financial crisis. The magnitude of the growth rate, however, was unexpected. During April 2020, year-over-year (YOY) growth in the money supply was at 21.30 percent. That’s up from March’s rate of 11.3 percent, and up from April 2019’s rate of 1.94 percent. Historically, this is a very large surge in growth both month over month and year over year. It is also

Topics:

Ryan McMaken considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

RIA Team writes The Importance of Emergency Funds in Retirement Planning

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Gesetzesvorschlag in Arizona: Wird Bitcoin bald zur Staatsreserve?

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes So bewegen sich Bitcoin & Co. heute

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Aktueller Marktbericht zu Bitcoin & Co.

Fueled by unprecedented quantitative easing, central bank asset purchases, and various stimulus packages, the money supply growth rate ballooned in April to an all-time high. The growth rate has never been higher, with the 1970s as the only period that comes close. It was expected that money supply growth would surge in recent months. This usually happens in the wake of the early months of a recession or financial crisis. The magnitude of the growth rate, however, was unexpected.

|

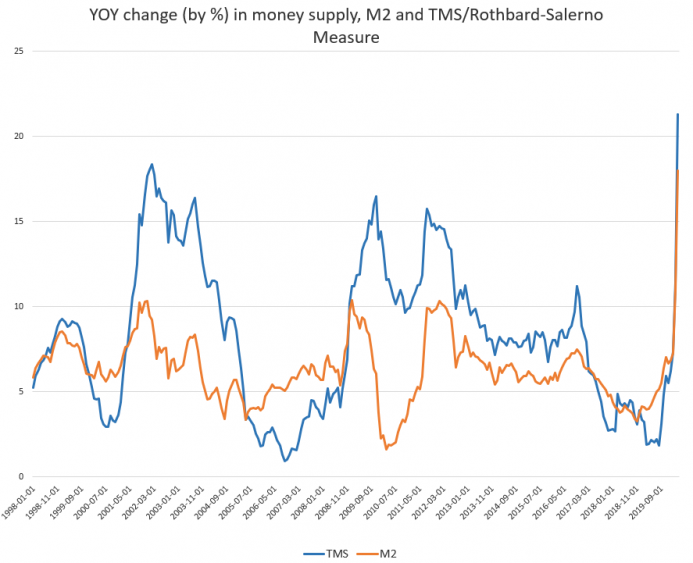

During April 2020, year-over-year (YOY) growth in the money supply was at 21.30 percent. That’s up from March’s rate of 11.3 percent, and up from April 2019’s rate of 1.94 percent. Historically, this is a very large surge in growth both month over month and year over year. It is also quite a reversal from the trend that only just ended in August of last year, when growth rates were nearly bottoming out around 2 percent. In August, the growth rate hit a 120-month low, falling to the lowest growth rates we’d seen since 2007. The money supply metric used here—the “true” or Rothbard-Salerno money supply measure (TMS)—is the metric developed by Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno, and is designed to provide a better measure of money supply fluctuations than M2. The Mises Institute now offers regular updates on this metric and its growth. This measure of the money supply differs from M2 in that it includes Treasury deposits at the Fed (and excludes short-time deposits, traveler’s checks, and retail money funds). The M2 growth rate also increased to historic highs in April, growing 18.01 percent compared to March’s growth rate of 10.95 percent. M2 grew 4.0 percent during April of last year. The M2 growth rate had fallen considerably from late 2016 to late 2018, but has been growing again in recent months. As of March, it is following the same trend as TMS. |

YoY Change in money supply, 1998-2019 |

| Money supply growth can often be a helpful measure of economic activity. During periods of economic boom, money supply tends to grow quickly as banks make more loans. Recessions, on the other hand, tend to be preceded by periods of slowdown in rates of money supply growth. However, money supply growth tends to grow out of its low-growth trough well before the onset of recession. As recession nears, the TMS growth rate climbs and becomes larger than the M2 growth rate. This occurred in the early months of the 2002 and the 2009 crises. February 2020 was the first month since late 2008 that the TMS growth rate climbed higher than the M2 growth rate. The TMS growth rate again exceeded M2 in March and April 2020. As of mid-April 2020, it does appear that the decline in money supply growth has again preceded a recession. Although some observers will likely claim that the current economic crisis is a result solely of the COVID-19 panic and resulting government-forced shutdowns, several indicators do suggests that the economy was primed for a recession. The decline in TMS is one of these indicators, as is the late 2019 liquidity crisis in the repo markets. The Fed’s moves to drop interest rates and to once again grow its balance sheet speak to the weakness of the economy leading up to April 2020.

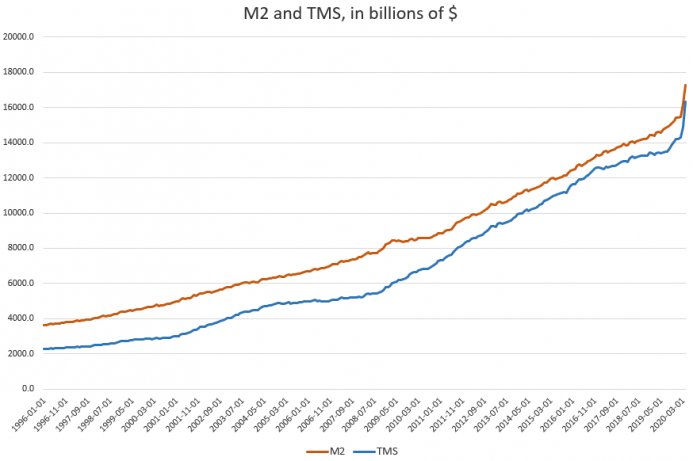

The overall M2 total money supply in February was $17.2 trillion and the TMS total was $16.3 trillion. |

M2 and TMS, in billions of $, 1996-2020 |

| The growth in the money supply in recent months is in part tied to the fact that the Federal Reserve grew more accommodative in late 2019 and embraced unprecedented monetary stimulus in March and April. The Fed drove down the target key interest rate to 0.25 percent and began broad and unprecedented new “quantitative easing” programs. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) cut the target fed funds rate more than once in the months preceding March 2020, but in response to government-forced shutdowns of several sectors of the economy, it cut the federal funds rate by 150 basis points in less than a month. The Fed has flooded markets with new money by purchasing a variety of assets from US government debt to securities. The Fed’s balance sheet is now at an all-time high.

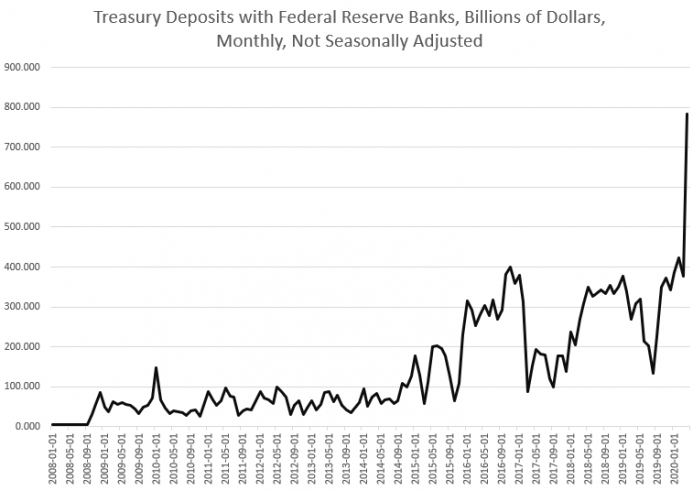

Another change partially driving the increase in the TMS is the large increase in Treasury deposits at the Fed that we’ve seen in recent months. In April 2020, this sum surged to a new all-time high of $783 billion. This is well in excess of the previous high of $423 billion reached during February of this year. |

Treasury Deposits with Federal Reserve Banks, 2008-2020 |

Tags: Featured,newsletter