Here’s the difference between a recession and a depression: you can’t get blood from a stone, or make an insolvent entity solvent with more debt.

There are two basic differences between a recession and a depression:

1. Duration: a recession typically lasts between 6 and 18 months, while a depression drags on for years or even decades, often masked by official propaganda as “slow growth” or “stagnation.”

2. The basic dynamic: recessions are business / credit cycle events that wring out the excesses of credit expansion (i.e. lending to unqualified borrowers who subsequently default) and mal-investment in low-yield, high-risk speculations and projects that only made financial sense in the euphoria of bubble psychology (i.e. animal spirits acting as if bubbles never pop).

Recessions are brief because the basic dynamic is to write down defaults, tighten up credit and absorb the losses from failed speculations. As consumers and enterprises cut back borrowing, they trim spending, leading to lay-offs, reduced tax revenues, contraction of credit and all the other consequences of wringing excesses out of the economy.

But once the losses have been absorbed and insolvent households and enterprises have worked through bankruptcy, then the decks are cleared for a renewed credit / business cycle expansion.

Depressions, on the other hand, are generated by self-reinforcing feedback loops: insolvencies beget more insolvencies, reduced prices for assets beget lower prices for assets, and so on.

There are two critical differences between the two dynamics: high fixed costs and dependence on credit / asset bubbles for “growth.” Recessions clear excesses in otherwise healthy economies with low fixed costs, rising productivity, broadly distributed gains in earned income, safe yields on capital set aside for savings and retirement and high returns on productive investments. Growth is the result of rising productivity of labor and capital.

Depressions are the result of the opposite set of dynamics: growth is the result of a vast expansion of credit that drives mal-investment and risk-laden speculation. Productivity stagnates as capital flows to speculative gambles (“sure things” in a bubble euphoria) and expansions of capacity that far outstrip demand.

In these credit / speculative driven economies, capital is forced to “chase yield,” i.e. seek a return in risk assets rather than in low-risk secure investments. Soon, everyone is dependent on credit / asset bubbles for their paychecks, increases in wealth, pensions, sales, tax revenues, etc.

Economies prone to depressions have high debt levels and high fixed costs.Both generate self-reinforcing feedback loops: as loans issued to uncreditworthy borrowers default, liquidity dries up and marginal borrowers are pushed into default. As credit dries up, sales decline, profits drop, employees are laid off to cut operational costs and previously sound borrowers slide into default.

As defaults beget more defaults, lenders are pushed into insolvency, sparking a banking crisis. Borrowers sell assets at fire-sale prices to raise cash, pushing assets prices lower, putting borrowers underwater. As this insolvency is liquidated in bankruptcy / defaults, lenders must sell assets, driving prices ever lower in a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

The key here is to understand the difference between fixed costs and operational costs. Fixed costs are, well, fixed: they don’t decline even if income, sales or tax revenues decline. Fixed costs include: rent, mortgage payments, debt service, mandated healthcare insurance premiums, etc.

Operational costs decline rapidly in recessions; fixed costs don’t. Operational costs include wages paid to recent hires, fuel for the company trucks, etc. As business slows, some employees are laid off, reducing costs, and company vehicles log fewer miles, reducing fuel costs, and so on.

Fixed costs remain the same even as sales, profits, income and tax revenues plummet. Economies burdened with high fixed costs have very little wiggle-room (i.e. buffers) before reductions in sales, profits, income and tax revenues trigger losses, i.e. expenses are no longer covered by income.

| Here are some examples of fixed costs:

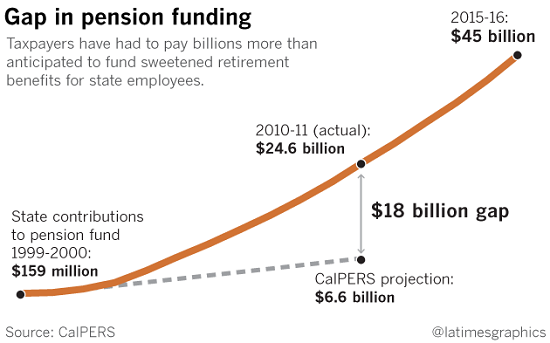

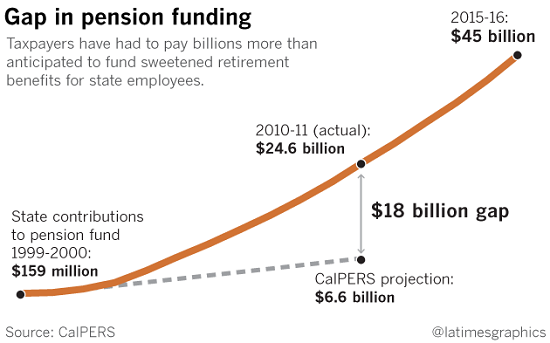

For state and local governments, pensions and benefits due retirees are fixed:they don’t go down in recessions. Rather, what drops in recessions are the tax revenues needed to fund the pensions.

California pension funding: |

Gap in pension funding 2015-2016 - Click to enlarge |

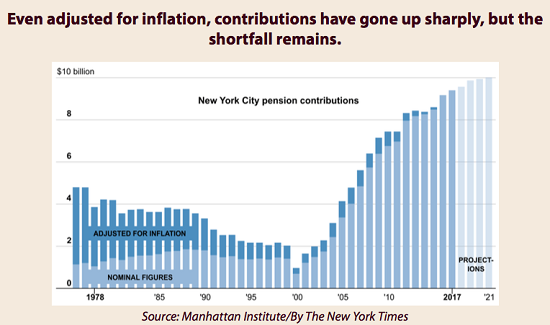

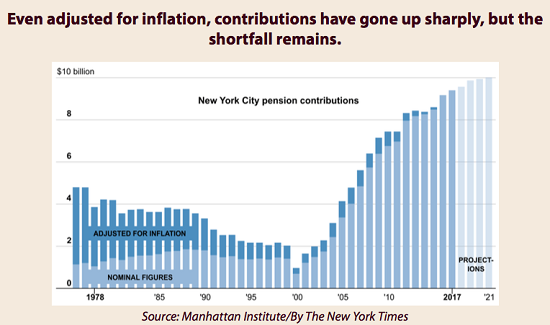

| New York City pension funding: |

NYC pension contributions 1978-2021 - Click to enlarge |

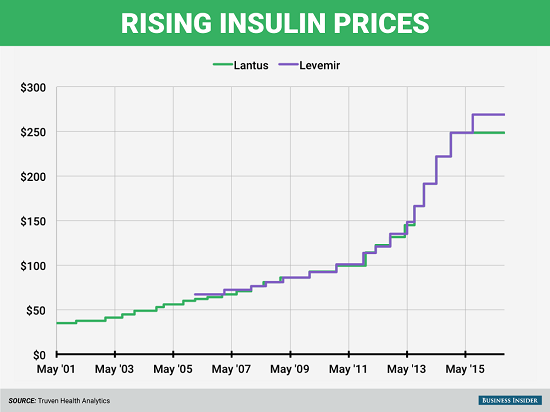

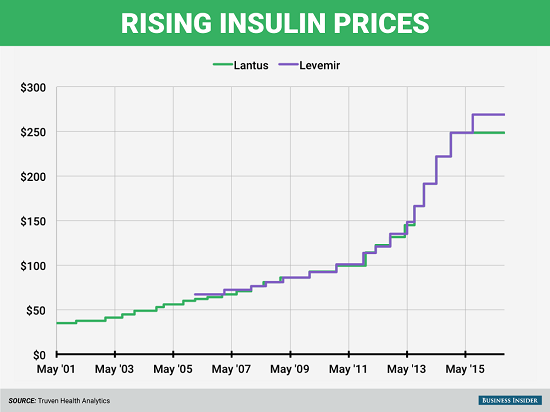

| Insulin is another fixed cost. Those needing insulin don’t stop needing it in recessions. Notice the enormous increase in the cost of insulin, i.e. inflation. |

Rising insulin prices 2001-2015 - Click to enlarge |

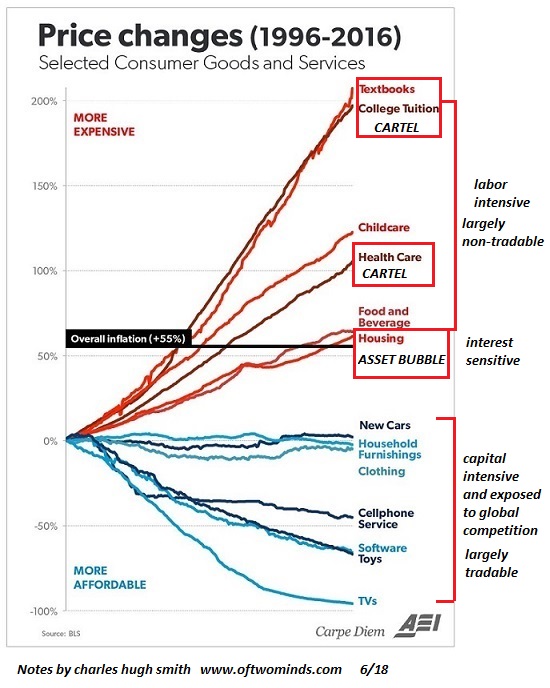

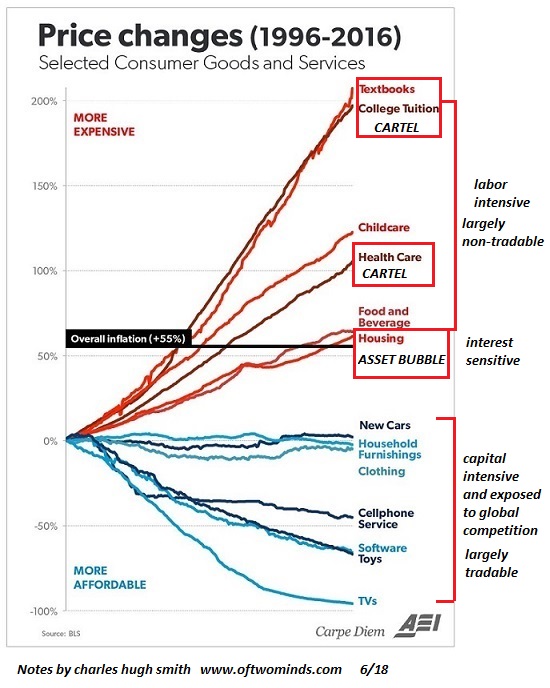

| Notice how all the big-ticket essentials (i.e. fixed costs) are rising in price: the only items with declining prices are those that are generally optional– TVs, clothing, etc. |

Price changes 1996-2016 - Click to enlarge |

Everywhere we look in the U.S. economy, we see sky-high fixed costs. Investors who overpaid for commercial real estate will default once their business tenants close down, homeowners who overpaid will default once one of the household’s primary jobholders loses his/her job, state and local governments that have feasted on a decade of rising tax revenues will suddenly face staggering deficits as tax revenues crater–the list of those with high fixed costs and no wiggle room other than bankruptcy is essentially endless in America.

Here’s the difference between a recession and a depression: you can’t get blood from a stone, or make an insolvent entity solvent with more debt. Losses will have to taken, and nose-bleed fixed-costs will have to be slashed; reality will eventually have to be dealt with.

My new book is The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake. For more, please visit the book's website.

Tags:

Featured,

newsletter