Just 11 days after Portuguese Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho took office, the new left-wing majority yesterday voted down the government’s programme leading to the collapse of the minority centre-right coalition (PàF). In the general election on 4 October, the PàF coalition, led by Pedro Passos Coelho, claimed the largest share of the popular vote (38.4%), but failed to retain its parliamentary majority as it obtained just 107 seats of the 230 seats in parliament. The Socialist Party came second with 32.3% (86 seats), while the smaller leftwing parties — Left bloc (BE) and the Democratic Unitarian Coalition (CDU)1) — claimed 10.2% (19 seats) and 8.3% (17 seats) respectively. After inconclusive negotiations between parties, Portuguese President, Anibal Cavaco Silva, reappointed Mr Passos Coelho as a prime minister. In the meantime, the Socialist and other leftist parties — Left Bloc (BE), the Communist Party (PCP) and the Greens (PEV) — formalised an agreement over the weekend, to vote down the government programme of the centre-right coalition (PàF), causing the coalition to collapse yesterday. The new leftwing majority has now 122 seats in the 230-seat parliament. November is set to mark an historical period in Portuguese politics. Socialists and Communists have not formed a coalition for 40 years.

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: Macroview, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

Claudio Grass writes The Case Against Fordism

Claudio Grass writes “Does The West Have Any Hope? What Can We All Do?”

Claudio Grass writes Predictions vs. Convictions

Claudio Grass writes Swissgrams: the natural progression of the Krugerrand in the digital age

Just 11 days after Portuguese Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho took office, the new left-wing majority yesterday voted down the government’s programme leading to the collapse of the minority centre-right coalition (PàF).

In the general election on 4 October, the PàF coalition, led by Pedro Passos Coelho, claimed the largest share of the popular vote (38.4%), but failed to retain its parliamentary majority as it obtained just 107 seats of the 230 seats in parliament. The Socialist Party came second with 32.3% (86 seats), while the smaller leftwing parties — Left bloc (BE) and the Democratic Unitarian Coalition (CDU)1) — claimed 10.2% (19 seats) and 8.3% (17 seats) respectively. After inconclusive negotiations between parties, Portuguese President, Anibal Cavaco Silva, reappointed Mr Passos Coelho as a prime minister.

In the meantime, the Socialist and other leftist parties — Left Bloc (BE), the Communist Party (PCP) and the Greens (PEV) — formalised an agreement over the weekend, to vote down the government programme of the centre-right coalition (PàF), causing the coalition to collapse yesterday. The new leftwing majority has now 122 seats in the 230-seat parliament.

November is set to mark an historical period in Portuguese politics. Socialists and Communists have not formed a coalition for 40 years. Moreover, for the first time since the Revolution of 1974, the party (coalition in case of PàF) which won the elections will not be in power. So far, parliament had always made the winning party rule.

What’s next

The Portuguese president must decide whether to allow Mr Passos Coelho (PàF) to head a caretaker government until elections are held or to grant power to the socialist leader Antonio Costa (PS), supported by the far left.

At this stage, the president’s decision remains highly uncertain. In his latest statement, the president expressed concern over appointing a government that would depend on “anti-European forces” such as BE and PCP. This suggests that he might opt for the former solution and call new elections. However, under the constitution, an election cannot be held before May-June 2016, implying a delay in the 2016 Budget. Moreover, the pact between the Socialists and other parties of the left does not refer to any time limit, thereby meeting the president’s demand for a stable government. Given this, and the fact that a caretaker government can be seen as an undemocratic solution, the Portuguese president is more likely to ask Antonio Costa to form an alternative government.

Funding consequences for Portugal

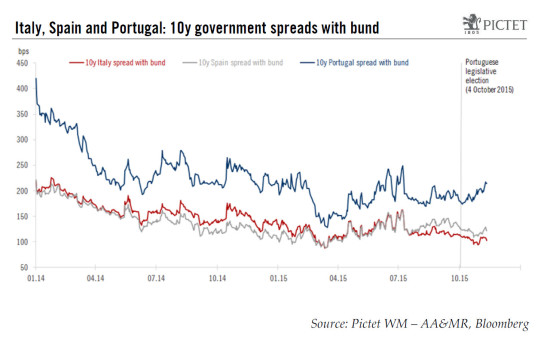

Rising political uncertainty is likely to weigh both on Portugal’s economic prospects and financial conditions. Sovereign bond yields have widened since the political crisis started, with the 10-year spread versus German Bunds rising by around 40bp to 215bp, though still well within its July high of 250bp.

Near-term, the main risk for Portuguese bonds may be related to the ECB’s decision to keep buying them as part of its QE (PSPP) programme. The ECB has set simple and transparent rules in terms of QE eligibility – the recipient country needs to fulfil the collateral eligibility criteria for marketable assets which were restated in the PSPP legal act. Portugal exited its financial assistance programme in June 2014 and the country received a further positive assessment as part of the Troika’s Post-Programme Surveillance (PPS) mission in June 2015, although the ECB noted that “the pace of structural reform implementation remains moderate”. Therefore, the standard eligibility criteria apply, including the so-called first-best rule whereby at least one ratings agency out of the four the ECB considers needs to apply an investment-grade rating (BBB- or above) for the country’s debt to be eligible for ECB refinancing operations and QE.

The Canadian ratings agency DBRS is one of them and the only one to still have Portugal above the investment-grade threshold, at BBB. Incidentally, DBRS is due to review Portugal’s rating on Friday (November 14). In general, DBRS is used to take decisions based on a number of structural factors rather than to overreact to political events. On 2 October, it issued a statement noting that “coming elections in Portugal pose limited political risks, but policy challenges persist”. Its view could change in light of recent developments, although perhaps the most likely outcome is that it assigns a negative outlook to the rating while refraining from cutting it.

Even in the event of a downgrade, the ECB retains the final decision and it could arguably make an exception if there is a prospect of a swift resolution to the political crisis. It has done so in similar situations in Greece in the past. On the other hand, stopping purchases of Portuguese bonds may be seen as the natural decision and possibly another way to put pressure on the (next) government to comply with European recommendations. Either way, assuming political stability returns eventually, there is no fundamental reason to believe that Portugal could be excluded from QE for more than a short period of time.

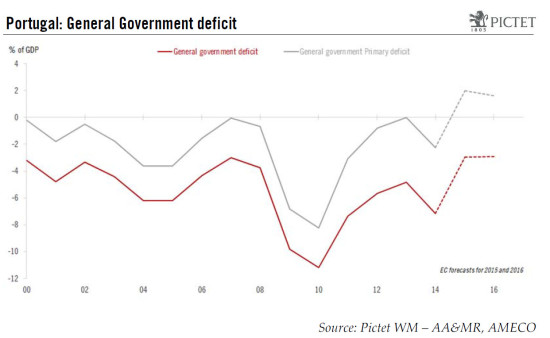

Overall, the key for Portugal’s funding conditions and future rating will be the macroeconomic policies of the new leftist government. The Socialists have pledged to reverse the pensions freeze and public sector wage cuts implemented as a condition for Portugal’s bailout in 2011, to increase minimum wages (currently set at €505-€600 by 2019), decrease sales VAT in restaurants (currently 23%), restore some public holidays (four were lost in 2013) and reverse some privatisations. Mr Costa has expressed his commitment to taking Portugal out of the Excessive Deficit Procedure by reducing the public deficit below 3% of GDP, but at this stage, it is not clear how the country will reach this target with the government's proposals and with the proposal of its new allies. The latter have already dropped some of their previous radical proposals including a euro area exit, but concerns remain about the strength of the alliances given the Socialists’ more moderate stance and the much more radial stance of the other two parties. Political uncertainty is therefore likely to weigh on Portugal in the months ahead, but systemic risk remains low.

1) Democratic Unity Coalition (CDU) is a coalition of the Portuguese Communist party (PCP) and the Green Party