Quarterly wage data (ECI) for Q3 pointed to modest increases, and core PCE inflation remained stable at a low 1.3% in September. Although the October FOMC statement was surprisingly hawkish, we continue to believe that the most likely scenario will see the Fed biding its time until March next year before making a start on lifting rates. Friday saw some key data being published: the quarterly Employment Cost Index (ECI), admittedly the most reliable measure of wages and salaries. Following last week’s more hawkish FOMC statement and with the Fed in ‘data-dependency’ mode, prolonged uncertainty over inflation prospects and surprisingly weak average hourly earnings numbers in September – the other main statistic on wages – publication of these Q3 ECI data was of particular significance. Wage growth remained muted in Q3 The Employment Cost Index rose by 0.6% q-o-q (2.3% annualised) in Q3, in line with consensus estimates. This followed on from a very modest 0.2% rise in Q2. As the q-o-q increase was slightly higher in Q3 last year, the y-o-y rise in the ECI eased from 2.0% in Q2 to 1.9% in Q3. This statistic can be quite volatile in the short run, and there were odd big swings in wages in H1. However, so far in 2015, the ECI has advanced by only 2.1% y-o-y, compared with 2.1% as well on average in 2014 and 1.9% in 2013.

Topics:

Bernard Lambert considers the following as important: Macroview, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

Claudio Grass writes The Case Against Fordism

Claudio Grass writes “Does The West Have Any Hope? What Can We All Do?”

Claudio Grass writes Predictions vs. Convictions

Claudio Grass writes Swissgrams: the natural progression of the Krugerrand in the digital age

Quarterly wage data (ECI) for Q3 pointed to modest increases, and core PCE inflation remained stable at a low 1.3% in September.

Although the October FOMC statement was surprisingly hawkish, we continue to believe that the most likely scenario will see the Fed biding its time until March next year before making a start on lifting rates.

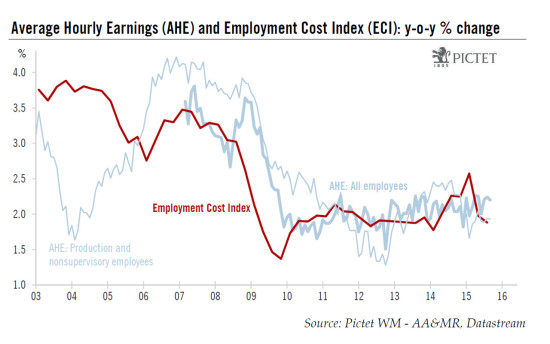

Friday saw some key data being published: the quarterly Employment Cost Index (ECI), admittedly the most reliable measure of wages and salaries. Following last week’s more hawkish FOMC statement and with the Fed in ‘data-dependency’ mode, prolonged uncertainty over inflation prospects and surprisingly weak average hourly earnings numbers in September – the other main statistic on wages – publication of these Q3 ECI data was of particular significance.

Wage growth remained muted in Q3

The Employment Cost Index rose by 0.6% q-o-q (2.3% annualised) in Q3, in line with consensus estimates. This followed on from a very modest 0.2% rise in Q2. As the q-o-q increase was slightly higher in Q3 last year, the y-o-y rise in the ECI eased from 2.0% in Q2 to 1.9% in Q3. This statistic can be quite volatile in the short run, and there were odd big swings in wages in H1. However, so far in 2015, the ECI has advanced by only 2.1% y-o-y, compared with 2.1% as well on average in 2014 and 1.9% in 2013. The current pace of increase in wages is certainly modest by past standards and most unlikely to generate any upward pressure on inflation.

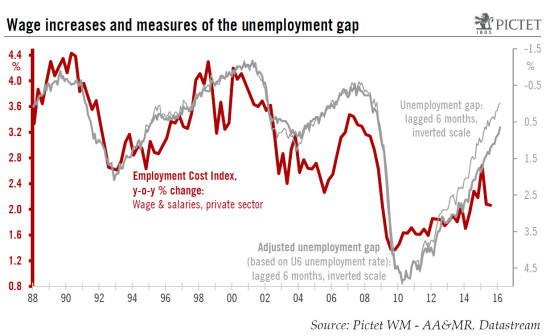

As for any potential upturn in the pace of wage increases, the analysis is by no means straightforward. The rate of recovery in GDP is relatively modest, the output gap probably remains quite noticeable and, as we have just seen, most measures of wages are continuing to rise at a very modest tempo. At the same time, though, the unemployment rate has continued to fall rapidly, and most indicators of the situation on the labour market have improved quite markedly of late. Although there is much discussion about the extent of slack in the labour market, there is no denying this slack is diminishing rapidly and that the US economy is approaching full employment. At some stage or another, the fall in unemployment can be expected to feed through and push wage inflation up (see chart below). We continue to expect wage increases to pick up gradually over the coming quarters.

Core PCE inflation still subdued

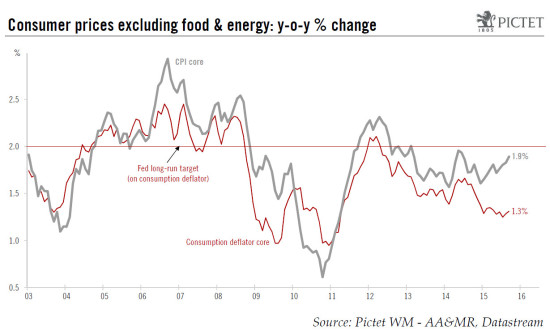

Importantly as well, Q3 data on the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) deflator were published last week as well as corresponding monthly numbers for September. September’s CPI figures have already been out for two weeks (see our post published on 15 October), but the PCE deflator is of particular pertinence because it is the price measure targeted by the Fed, and because its evolution has diverged quite significantly from the CPI’s so far this year (see the next chart).

At core level (i.e. excluding food and energy), the PCE price index edged up by 0.1% m-o-m in September, in line with consensus expectations. On a y-o-y basis, core PCE inflation was unchanged at 1.3%. Core PCE inflation remains very moderate for the time being and, overall, we continue to believe that y-o-y core PCE inflation will stay relatively stable over the next 6-9 months, before picking up modestly towards 1.6%-1.7% by the end of next year.

Unexpectedly hawkish FOMC statement

The October FOMC statement published on Wednesday sounded more hawkish than expected. Modifications in the paragraph describing economic developments were not particularly surprising though. The FOMC appeared more upbeat on consumption and investment, whilst acknowledging that “the pace of job gains slowed and the unemployment rate remained steady”. However, the Fed surprised with two noticeable changes. First, it dropped the warning sentence introduced in September stating that “recent global economic and financial developments may restrain economic activity somewhat and are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation in the near term”. Secondly, the sentence describing how the Fed determines “how long to maintain this target range” was modified to how the Fed determines “whether it will be appropriate to raise the target range at its next meeting”.

These two modifications were perceived as hawkish. They suggest the Fed is less worried about market stress and developments abroad, whilst the reference to the next meeting reaffirmed more forcefully that every meeting is ‘live’. Our view is that, with these changes to its statement, the Fed was just trying its best to convince markets the door was still open for a December hike. And, as things are, it seems to have worked, at least to a certain extent. Market pricing on probabilities of a hike in December have risen noticeably following the publication of the statement, moving up from around 33% on Tuesday to almost 50% currently.

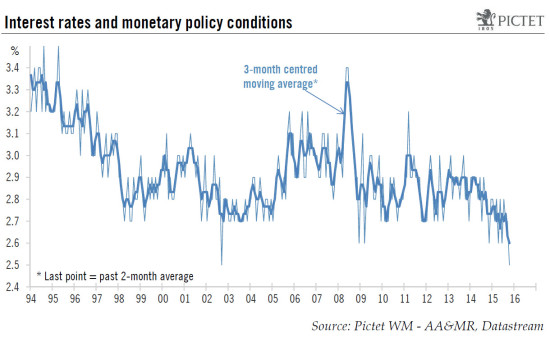

However, we would not view the rather hawkish FOMC statement as signalling any noticeable changes in the Fed’s underlying analysis of the situation. It is true that, since mid-September, market stress has receded noticeably and that concerns about growth in China and the emerging world have abated somewhat. However, this may turn out to be a temporary phenomenon, especially if an early Fed hike is becoming likelier. More importantly, most other elements the FOMC is considering in its analysis have not improved since the FOMC met in September. September’s employment report was soft, and most other economic data published of late – including yesterday’s Q3 GDP number – can be described as mixed at best. The trade-weighted dollar and long-term rates are roughly at the same levels as when the FOMC met in September. And, as we have just seen, core inflation at PCE level remained pretty low in September, and wage inflation as well in Q3. Moreover, one of the important reasons why the FOMC held fire in September was the prolonged low level of inflation and decline in market inflation expectations. In a conference later in September, Chair Yellen emphasised the importance of inflation expectations remaining well anchored. Unfortunately, on that front, things have not improved since mid-September. Market measures of inflation expectations have dropped further and, according to the Michigan sentiment survey, consumer inflation expectations for the next 5-10 years declined further in October. In fact, on a 3-month moving average basis, this measure of long-term inflation expectations has just reached a historical low (see chart below).

Admittedly, the situation described above may change over the coming weeks. Of particular importance will be the two upcoming employment reports, but inflation data, developments abroad and the behaviour of the dollar and of global financial conditions will also bring their influence to bear. The FOMC is in ‘data-dependency’ mode, and a December hike is a distinct possibility, provided upcoming data improve sufficiently. And, following the rather hawkish statement delivered this week, the probabilities of a December hike have risen. However, for the time being, we think that Fed confidence “that inflation will move back toward its 2 per cent objective over the medium term” will not improve by enough to lead to a hike as early as December. We continue to believe the FOMC will give priority to ‘risk management’ and, therefore, be more likely to wait until March next year before starting to hike rates.