The Washington Post began this week by noting how the US economy seems to have lost its purported zip just when it needed that vitality the most. Never missing a chance to take a partisan swipe, of course, still there’s quite a lot of truth behind the charge. An actual economic boom produces cushion, enough of one that President Trump and his administration may have been counting on it when opting for full-blown shutdown. The coronavirus recession is exposing how the economy was not strong as it seemed https://t.co/ZEtH0vUJ2M — The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) March 29, 2020 Instead, more and more it looks as if everything just crumbled like a sand castle exposed in the rain. And it’s not as if there weren’t warning signs; underneath the glowing

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, China, currencies, economy, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, GFC2, Markets, nbs manufacturing pmi, nbs non-manufacturing pmi, newsletter, PMI

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

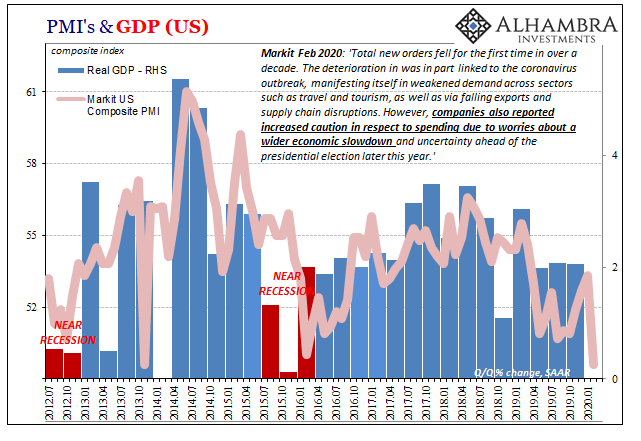

The Washington Post began this week by noting how the US economy seems to have lost its purported zip just when it needed that vitality the most. Never missing a chance to take a partisan swipe, of course, still there’s quite a lot of truth behind the charge. An actual economic boom produces cushion, enough of one that President Trump and his administration may have been counting on it when opting for full-blown shutdown.

The coronavirus recession is exposing how the economy was not strong as it seemed https://t.co/ZEtH0vUJ2M

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) March 29, 2020

Instead, more and more it looks as if everything just crumbled like a sand castle exposed in the rain. And it’s not as if there weren’t warning signs; underneath the glowing headlines (many of them published by this same Washington Post) touting that formerly sparkling unemployment rate were survey after survey about how there had been an enormous proportion of workers who were always one paycheck away from beyond broke (I know this because M. Simmons sends me copies of, or links to, every single one).

This isn’t just about the restaurant industry. Many of the nation’s small businesses – of all types – won’t survive. Even if we somehow manage to get most of the workforce back to work and do it in record time, there’ll still be behavioral changes in the short term (caution) that will also end up lingering long after the coronavirus is forgotten (more general frugality).

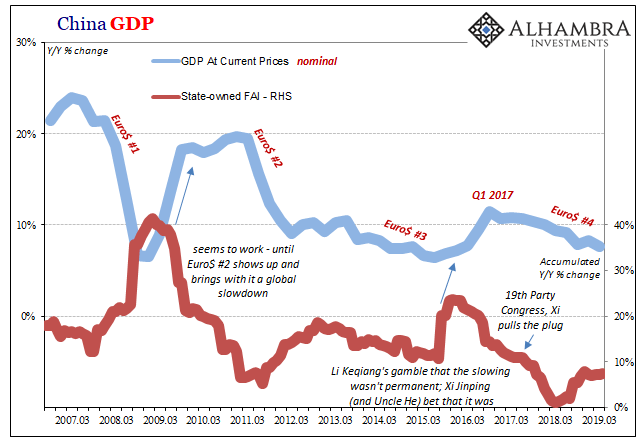

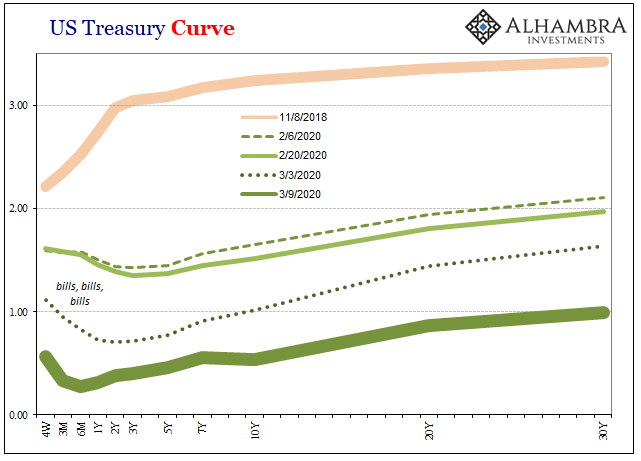

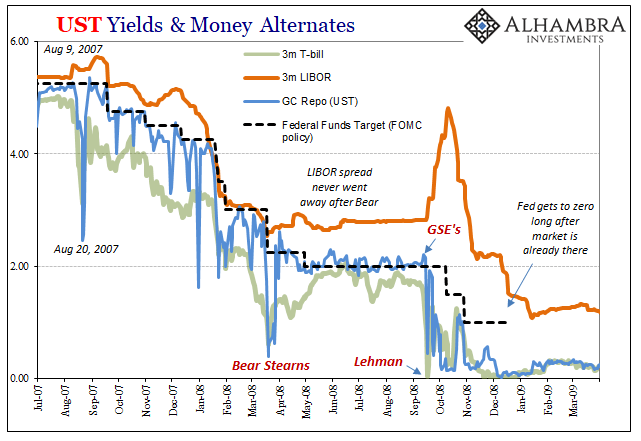

And that’s assuming there isn’t much fallout from GFC2, a eurodollar tsunami of a global shortage the vast bulk of which we’ve yet to experience. What happened earlier this month was the water disappearing from the beaches, the warning of the actual wave’s approaching menace.

Unfortunately, economic data over the coming months will only be marginally useful. It’s tainted by the unprecedented. There’s not much to compare it to therefore we’re struggling to put some framework around it in order to make any kind of reasonable interpretation.

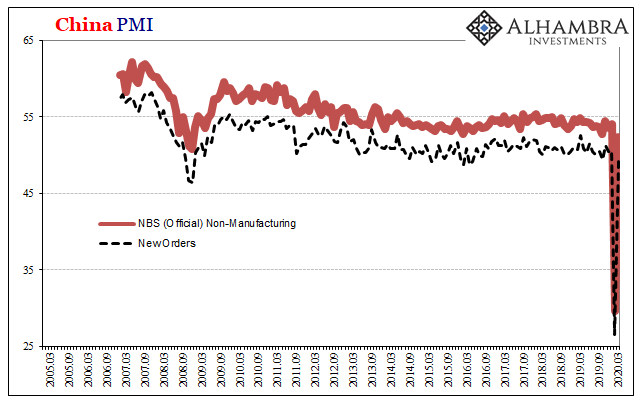

| So it is with the first slate of figures: those from China. The Chinese were first, obviously, in the pandemic fighting process. And it was their official PMI’s which had unveiled the record-setting nature of this first phase of global contraction. The numbers absolutely plummeted, followed shortly by China’s big three economic accounts (IP, retail sales, FAI) confirming the initial impulse.

But we already know that. What everyone wants to know now is how short the collapse might turn out to be so as to try to gauge how quickly the rebound comes. From there, perhaps some view on how strong it might be – smaller chances, everyone hopes, for long-term economic damage. The faster the global economy gets back going again, the greater the chance, it is being presumed, that a normal economy is just over the horizon. |

China PMI, 2005-2020 |

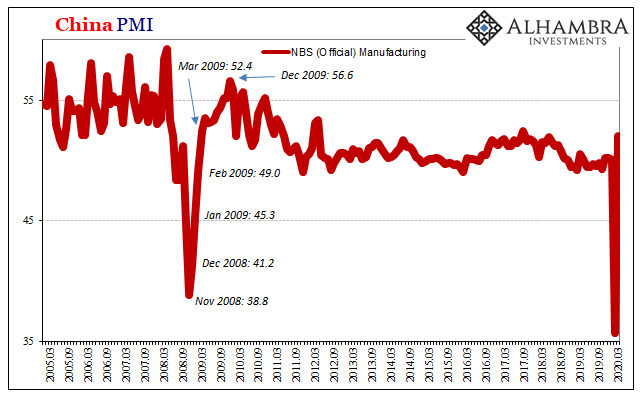

| On first glance, it appears that China’s NBS March 2020 PMI’s fall into that range. The Manufacturing Index had dropped down to 35.7 in February, non-manufacturing an incredible 29.6. Last night, the Chinese government said the turnaround had begun, the manufacturing PMI leaping up to 52 – the highest since September 2017 – while the non-manufacturing index also spiked to 52.3 (which remains at the low end of the historical range).

Best case scenario? Not quite. PMI’s are a weird sort of economic measurement. While being back above 50 is a sign that China’s economy is moving toward re-opening, the PMI’s don’t really have much to say about what that means. |

China PMI, 2005-2020 |

| A reading above 50 simply implies, in an oversimplified way, more firms are reporting gains in the particular categories than losses. Just above 50 is only a smaller favorable balance.

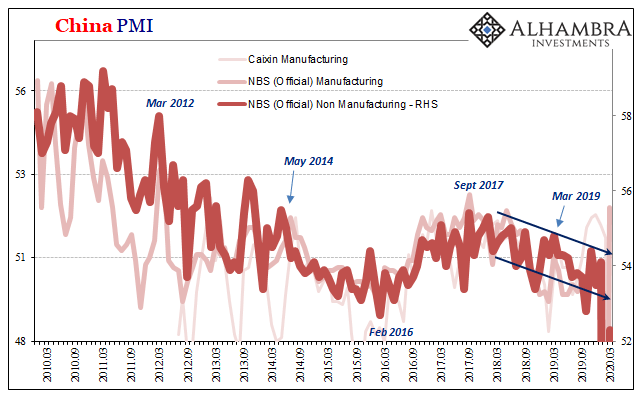

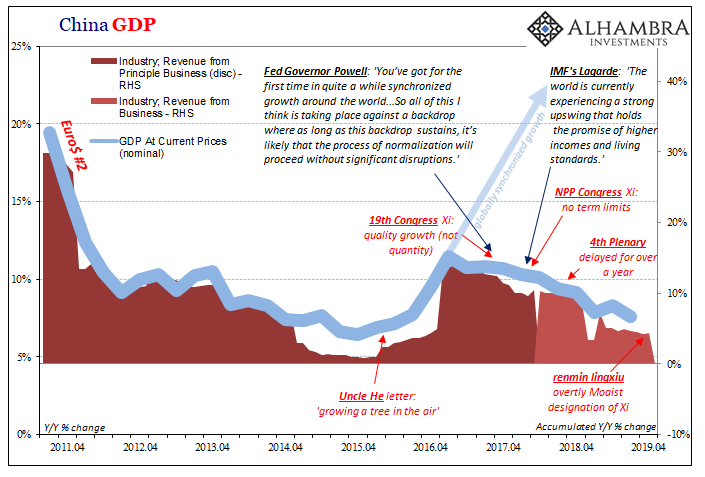

When the index falls to something like 35.7 or 29.6, what that meant was a near complete drop across the whole range of businesses in both economic segments. If the rebound was as instantaneous as people seem to be interpreting from these figures, then the PMI’s should have been something like 60 or even 70. All a 52 suggests when it follows a 35 is that it might not have gotten worse – in March. To immediately jump to the conclusion that it must be getting better is being impatient. Again, nobody really knows what the short run looks like, let alone anything beyond the short run. Furthermore, PMI’s are notoriously noisy month-to-month and there is every reason to suspect the volatility will be much higher given these circumstances. Considering government interference running in both directions, keeping some things shut down while getting other things restarted, both for non-economic reasons, this month’s numbers are of as little value as last month’s were. We also have to keep in mind that if the US economy hadn’t been as strong as it seemed (to some), China’s started out even weaker. In my own view, I’d have been more enthusiastic and optimistic had the numbers followed the 2008-09 pattern – steadily and more naturally coming back from the depths of the Great “Recession.” |

China PMI, 2010-2020(see more posts on China PMI, ) |

Instead, would anyone really be surprised if next month’s PMI’s sink back well below 50? After all, while China might be reopening (huge and still unconfirmed “if”) the rest of the world, China’s very customers, are just now closing up their wallets.

We won’t really get a good sense of things for several months. If by June China’s PMI’s are somewhere around 2009-10 levels, then we’ve got a chance.

Tags: China,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,GFC2,Markets,nbs manufacturing pmi,nbs non-manufacturing pmi,newsletter,PMI