Big Crunch or Big Chill Physicists say that the universe is expanding. However, they hotly debate (OK, pun intended as a foreshadowing device) if the rate of expansion is sufficient to overcome gravity—called escape velocity. It may seem like an arcane topic, but the consequences are dire either way. If the rate of expansion is too low, then it will get slower and slower until expansion stops entirely, then finally, begin collapsing again in a Big Crunch. That’s bad enough. But the other possible fate of the universe is even worse. If the expansion is fast enough, then the universe will keep expanding forever. Things will get colder and colder, until the state called the heat death occurs. If only economics had

Topics:

Keith Weiner considers the following as important: Central Banks, Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, newsletter, On Economy, On Politics

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Big Crunch or Big ChillPhysicists say that the universe is expanding. However, they hotly debate (OK, pun intended as a foreshadowing device) if the rate of expansion is sufficient to overcome gravity—called escape velocity. It may seem like an arcane topic, but the consequences are dire either way. If the rate of expansion is too low, then it will get slower and slower until expansion stops entirely, then finally, begin collapsing again in a Big Crunch. That’s bad enough. But the other possible fate of the universe is even worse. If the expansion is fast enough, then the universe will keep expanding forever. Things will get colder and colder, until the state called the heat death occurs. If only economics had similarly vigorous controversies. It faces its own existential problems. For example, there is an analogous concept to heat death in the economics universe. Will credit continue to grow, and with it the economy? Or will some force — or economic law — prevent, slow or stop it? |

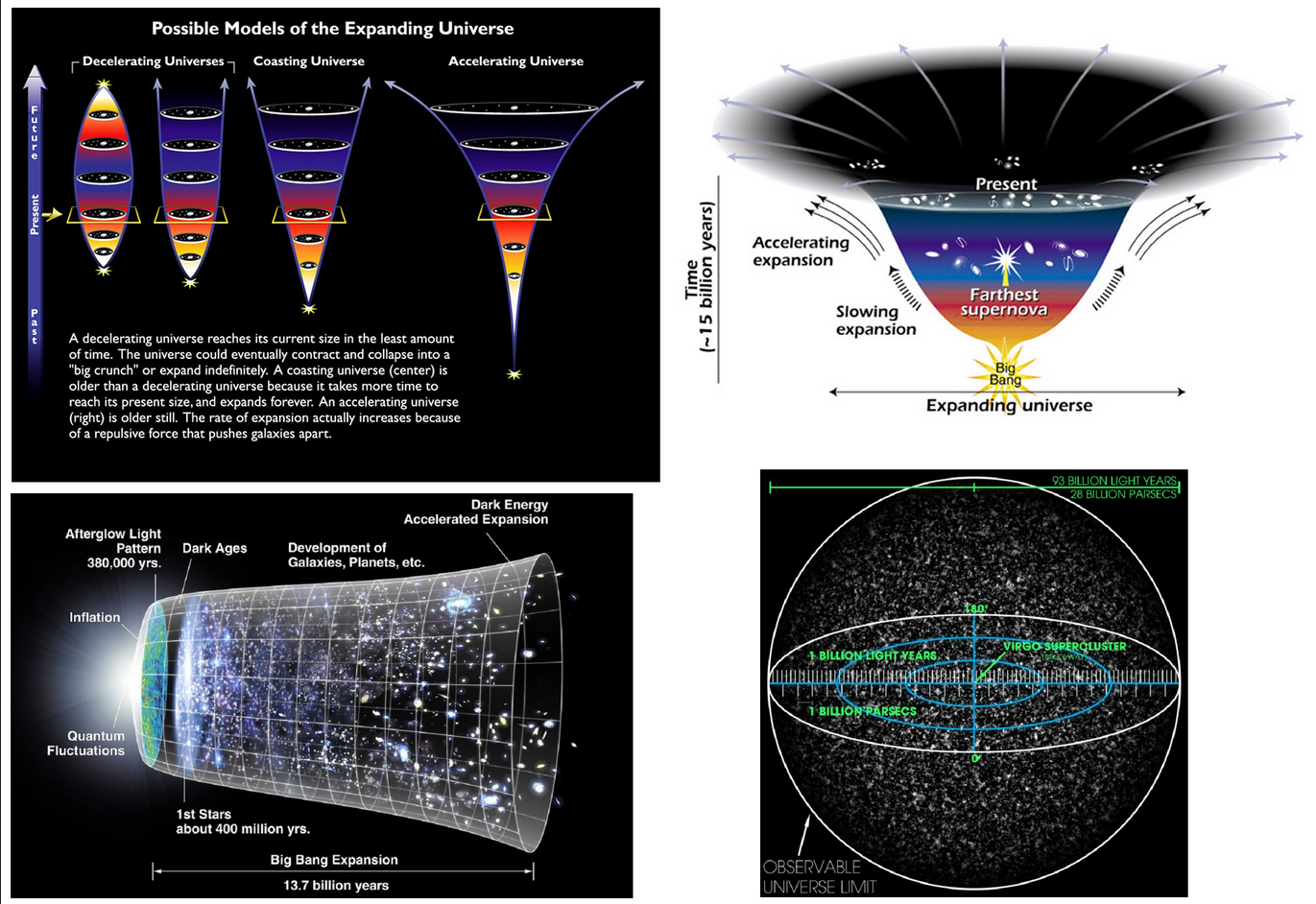

OT – a little cosmology excursion from your editor: Observations so far suggest that the expansion of the universe is indeed accelerating – the “big crunch”, in which the expansion not only stops, but reverses as it is overcome by gravity, is no longer deemed likely. Observation of distant supernovas and their red-shifts in the late 1990s pointed clearly to an accelerating expansion; this was the meantime confirmed by other data as well, such as those on fluctuations in the density of baryonic matter (baryon acoustic oscillations), which are evident in the large scale structures visible in the universe (ever larger structures are discovered, the record is currently held by the Hercules–Corona Borealis Great Wall, which measures an estimated ~3 gigaparsecs or roughly 10 billion light years across). - Click to enlarge The precise shape of the universe remains open to question, but recent evidence strongly suggests that it is a flat, Euclidian universe (thus, dark energy is assumed to be driving the acceleration of the expansion – a hyperbolic or saddle-shaped universe with a matter density below the critical value would expand forever anyway). The second and third image above show the current ideas about the timeline of the universe since the big bang. It is held that the current era of accelerating expansion started about 7.5 billion years ago. Ever since, all galaxies – indeed all objects in the universe – are flying apart at continually increasing speed. The last image shows the size of the observable universe, which has a diameter of 28.5 gigaparsecs, or 93 billion light years (i.e., we can “see” 46.5 billion light years in every direction). Readers will notice that this is much larger than the age of the universe would suggest. Shouldn’t the size of the observable universe be limited by the speed of light, and hence correlate roughly with the age of the universe? Actually, on account of the ongoing expansion of space-time, the light from the oldest, most distant galaxies we can currently see comes from objects that have moved much farther away from us in the meantime (a process referred to as “co-movement”). Over time, we will see more rather than fewer galaxies, as light will have had more time to travel and the light from even more distant galaxies will begin to reach us. The observable universe will grow, but there is a strict limit to this. The effect will reverse at an estimated threshold radius of 62 billion light years (compared to the current 46.5 billion), i.e., the maximum diameter of the observable universe will be capped at 124 billion light for all observers, regardless of where in the universe they are (note: all observers subjectively believe that they are at the center of the universe, as all of them can “see” a spherical volume of the same size surrounding them). Once this threshold is reached more galaxies will begin to red-shift out of visibility than will become newly visible, and eventually, darkness will descend on us, or rather, our descendants (trivia: the most remote quasar so far recorded by the Hubble telescope is a dark red blotch 31 billion light years from here). What is there beyond the boundary of the observable universe? Estimates of the size of the “causally disconnected” part of the universe (which we will never be able to see or interact with) range from 3×1023 times the size of the observable universe, up to a volume 101010122 times larger than what is visible to us. Both the “big rip”, in which the universe becomes cold and dark in a mere 22-50 billion years as the expansion accelerates to such an extent that every shred of matter is literally torn apart, or the “big freeze”, a slow heat death, in which maximum entropy is reached about 100 trillion years from now, remain possible alternatives for the end of everything. As the big freeze approaches its end, the last remains of baryonic matter will begin to degrade at temperatures a mere sliver above absolute zero, with protons and neutrons decaying into electrons and positrons that may form bizarre atoms light years in size (a.k.a. “positronium”), which will orbit each other at the ultimate snail’s pace, moving just one centimeter in a million years – in complete darkness, natch. All of this could still turn out to be wrong: our measurements may well be flawed; misled by effects caused by a relatively low matter density in our own sector of the universe and the nearby voids, which only make it appear as though the entire universe was expanding at an accelerating pace. It is also possible that as result of an unusually inhomogeneous distribution of matter (differences >20%), denser regions are actually already collapsing inward, but their contraction looks similar to an expansion from our perspective, due to the differences in the curvature of space in regions with varying matter density. Note that no “dark energy” would have to be invoked if that were the case. |

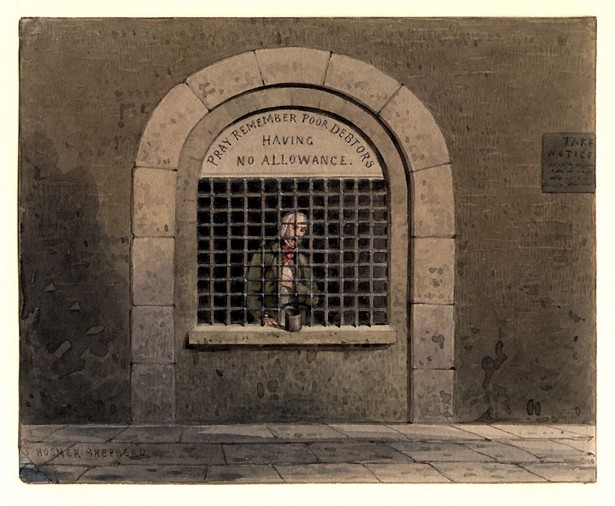

Sustainability and Monetary EntropyThere is a force that can cause the heat death of the economic universe. It is not the moralizing argument that faults man for the sin of wanting more material comfort, and condemns his desire for growth as hubris. Everyone needs growth. Even the environmentalists couch their anti-growth policies in euphemisms. They want us to stop using energy, but cannot openly promote energy poverty as an ideal. So they talk in terms of sustainability. Sustainability is an interesting concept. For a process or system to be sustainable, it means that there is no reason why it cannot continue indefinitely (well at least until the sun goes red giant and engulfs the Earth, which may not happen because before that our galaxy is on a collision course with the Andromeda galaxy…). Well, is our economy and its monetary system sustainable? How do you even approach this question in a rigorous way? We submit one fact for your consideration. To service debt, you must generate income. If you fail to pay at least the interest when due, creditors suffer big losses. This impairs their capacity and appetite to lend to others, which suffocates businesses who need capital to expand. So the key is generating enough income to pay interest. We would add on top of that the need to amortize the principal too. |

Members of an insane British environmentalist death cult led by Paul Kingsnorth (standing on the tree stump) attending the “Uncivilization Festival” (where they listen to “haunting music piped in from an iPod” – presumably, they expect iPods to grow on trees in the future). We have discussed these nutjobs in more detail in “The End is Nigh!” [PT] Photo credit: Bridget McKenzie - Click to enlarge |

|

The analogy to heat death of the universe is a pretty good fit. Physicists are not looking at one probe that is moving out of the solar system and will chill down to near absolute zero when its power supply runs out of juice. Nor one object, such as Pluto. They are looking at the universe and all entities in it including all stars and all life on all planets. Similarly, we as economists must look at the economic universe and all business enterprises and people in it. If one business is stranded with, e.g. an obsolete product such as mobile phone that can only do voice calls, it will fail and default on its debts. That is not under question. The question is: can it happen to the entire economy? If it does, then the monetary system will fail and everyone will lose their savings. If it can happen what are the circumstances? So far, we said income (that is net income, after cost of goods sold and all other expenses) must exceed debt service. And debt amortization should perhaps be included. Measuring these two quantities, much less estimating them years or decades in the future, would be quite a challenge. Just like measuring the velocities and distances of all objects in the universe. |

Pluto. Ever since he was demoted from “planet” to “just some distant trans-Neptunian pseudo-round object” in 2006, he’s in a bad mood and looks kind of grim. [PT] - Click to enlarge |

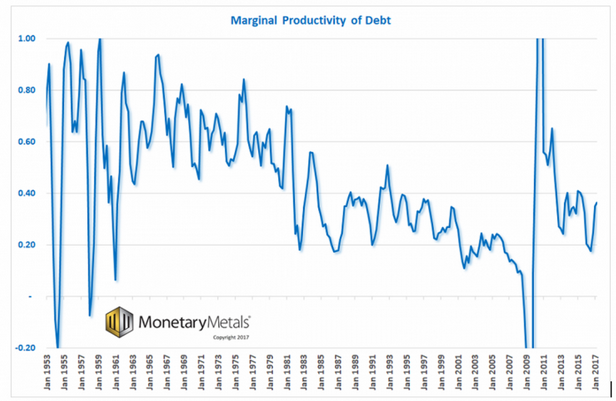

A Measure of SustainabilityFortunately, we can look at something else that makes this much easier. We know the economy is in motion today. So we just need to know the trend. If income is rising at least as fast as debt service costs, we can say that the economy is sustainable. We have been writing about this trend for the last month, though we did not describe it in this context. The variable we need to measure is none other than marginal productivity of debt! MPoD, as we will call it here for brevity, is a measure of how much new GDP is added for each freshly borrowed dollar. The graph we published on Oct 15 is included again here. Aside from the anomaly when MPoD moved up sharply in the wake of the great financial crisis (which we discussed here), it is an unmistakable falling trend. Post 2010, it is falling again from that higher level. This trend spans many decades, and it is no fluke. A falling MPoD means we get less and less GDP for each borrowed dollar. Or conversely, we have to borrow more and more dollars to get a dollar of GDP. This is significant as growth in net income can be no greater than growth in GDP (but it is likely a lot slower, a whole ‘nother topic). This graph is saying that the income to debt ratio is falling. |

Marginal productivity of debt 1953 - 2017 |

| We are getting close to our statement above, income must exceed debt service or else there will be a heat death of the economic universe. We have now proven income is growing slower than debt total. We have one more step, to prove income is growing slower than debt service.

Normally, debt service would grow proportionally with debt. It may seem fortunate that we don’t live in a normal universe, as we shall see in a moment. We live in an abnormal place, which is subject to one of the planks proposed by Karl Marx in his infamous Communist Manifesto.

|

|

The Business of “Profitable” Value-DestructionThe central bank conducts what it calls monetary policy. The net result of monetary policy for 36 years so far is falling interest rates. I have written about the various ways that falling interest causes destruction in his series of articles on yield purchasing power. However, in light of the heat death question, falling interest would seem to have the potential to save us. It is obvious that servicing the same debt at 1% interest has a lower monthly payment than at 10%. This is why many economists say there is no problem. We are told that, “debt service today is not a greater percentage of GDP than it was when the debt was much lower decades ago.” That may be true, and we won’t even get into if net income is the same percentage of GDP as it was (we would bet an ounce of fine gold against a soggy dollar bill it isn’t). We want to make a different argument. If debt service depends on falling interest, what happens when interest hits zero? Here is another good analogy to physics, which also asks what happens at zero. In physics, nothing. Literally. Motion stops on even a molecular level at absolute zero. What happens to an economy when interest — we mean the long-term bond rate — falls to zero? What happens when businesses can borrow at 0%? Well, obviously, debt service goes to zero (not including amortization of the principal). With no cost to borrow, businesses can borrow for activities that produce no economic value(!). |

|

In a normal economic universe, interest is greater than zero. As we said last week:

At zero, this economic law is violated. No one can act as if he had no time preference, which is exactly what zero interest requires him to do. And zero, itself, is not sustainable anyway. Assuming that some amount of amortization is required, then the debt service becomes unbearable and the interest rate must keep falling. When interest is positive, or even zero, business borrowing must fund activities that generate a positive return (even if only share buybacks). However, when interest goes negative, they can borrow to engage in capital-destroying activities. So long as the rate of destruction is below the rate of interest. For example, suppose an enterprise destroys its investors’ capital at 1% per year. That’s bad. But what if it can borrow this capital at -2%? The investors lose 2% per year. But the business nets +1%. Positive one percent. What is profitable to do, will be done at large scale across the entire economic universe. At negative rates, investors lose a bit of their capital every year. They are subsidizing businesses who are destroying it bit by bit every year. |

Example of a business activity with dubious earnings prospects, highly likely to require ZIRP: electroplating the dead. [PT] Image via fineartamerica.com - Click to enlarge |

Heat Death ConditionsNegative interest rates are not sustainable. A falling interest rate can make debt service cheaper. However, it does not solve the problem of falling marginal productivity of debt. The heat death of the economic universe looms closer every day (we make no prediction of the timing of this here, that will be the subject of a future series). So now we can write an economic law:

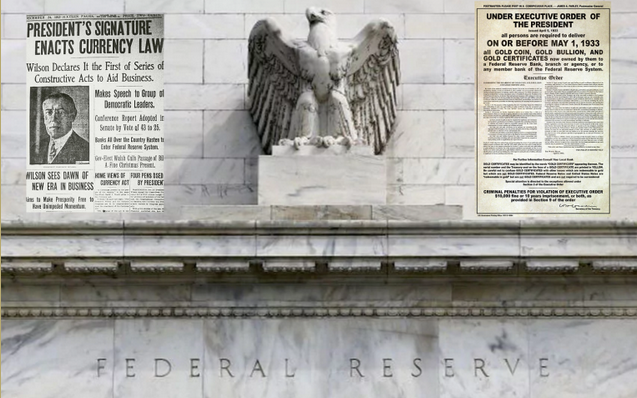

That is, the heat death of the economic universe is inevitable. Note that MPoD was under 1 even as long ago as the 1950’s (we suspect this pathology began either around the time of President Roosevelt’s gold confiscation in 1933, or the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, but we don’t have the data going back that far). The temple of fraud… left: a newspaper article reporting on the pre-Christmas coup that established the central bank in 1913 fails to even mention the central bank (it’s just a “constructive act to aid business”); right: the infamous FDR decree proclaiming the possession of gold illegal and telling the rubes their gold was about to be confiscated. The paper dollars they received in return were devalued by 70% almost immediately thereafter. This goes to show that it is generally never a good idea to live under “great presidents” – the experience usually leaves countless people dead and/or a lot poorer. As a rule it is much better for the common man if his presidents are almost certain to be considered a “failure” by historians, or have the decency to spend most of their presidency on their deathbed such as Garfield, who “never found the time to accomplish his plans” to everybody’s vast relief. (see also Bill Bonner’s article on these underrated national treasures). Prior to the crisis of 2008, MPoD fell below 0.1. Even now with its post-crisis boost, it is well under 0.4, and falling. It is time for gold to enter the mainstream monetary discussion. Interest rates and MPoD do not fall when there is a free market in money and credit. And the market will choose gold, if it is free to do so. |

Chart by: Monetary Metals

Image captions by PT

Tags: central banks,Featured,newsletter,On Economy,On Politics