Unknowable Degrees of Bubble Insanity Back in February, we brought you an update on the truly insane real estate bubble in Australia (see: “Australia’s Housing Bubble – In the Grip of Insanity” for details) in the wake of Jonathan Tepper of Variant Perception reporting on an eye-opening fact-finding tour in Sydney. This rotting shack in Sydney and its tiny plot of land sold for nearly million in May of 2014 – more than two years ago. Since then, house prices in Australia have increased even further. Yes, it is an insane bubble, no doubt about it. Photo credit: Attila Szilvasi - Click to enlarge As every seasoned market observer knows though, the fact that a bubble has obviously attained crazy proportions does not mean it cannot become even crazier. We only need to think back to the Nikkei index in the late 1980s, the Nasdaq in the late 1990s, or the grand-daddy of modern-day bubble insanity, the Souk Al-Manakh bubble in Kuwait in the early 1980s. The latter example is generally less well known than the others, but it is unsurpassed in terms of sheer mass dementia.

Topics:

Pater Tenebrarum considers the following as important: Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, newslettersent, Real estate

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Mark Thornton writes Is Amazon a Union-Busting Leviathan?

Unknowable Degrees of Bubble InsanityBack in February, we brought you an update on the truly insane real estate bubble in Australia (see: “Australia’s Housing Bubble – In the Grip of Insanity” for details) in the wake of Jonathan Tepper of Variant Perception reporting on an eye-opening fact-finding tour in Sydney. |

|

| As every seasoned market observer knows though, the fact that a bubble has obviously attained crazy proportions does not mean it cannot become even crazier. We only need to think back to the Nikkei index in the late 1980s, the Nasdaq in the late 1990s, or the grand-daddy of modern-day bubble insanity, the Souk Al-Manakh bubble in Kuwait in the early 1980s.

The latter example is generally less well known than the others, but it is unsurpassed in terms of sheer mass dementia. What made this bubble so special – at its peak Kuwait’s stock market had a total capitalization of more than $100 billion, which made it the third-largest equity market in the world behind the US and Japan at the time, a fact that should have told market participants they were skating on very thin ice – was the use of post-dated checks to pay for stock purchases. The bubble needed a trigger to pop, and that trigger was delivered when one day, a single one of these post-dated checks actually bounced. One of the biggest market crashes in history ensued – a truly dramatic wipe-out, that in the end destroyed the country’s entire OTC stock market. As we have pointed out previously, while residential real estate is actually a consumer good, analytically it should be treated as akin to a capital good maintained over several consecutive stages of production, as it renders its services over a very long period of time (the same principle holds for other durable goods – see J.H. de Soto, Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles). One implication of this is that interest rates are very important to the valuation of real estate. At present, the administered central bank interest rate in Australia is at a new low, and since it remains actually high compared to similar rates in other developed countries, it may well decline even further. |

Australia Interest Rate |

| Gross market rates all over the world have so far continued to follow the downtrend in central bank rates, so the market has yet to reassert itself (we plan to post an in-depth discussion of the current trend in gross market rates soon). As long as rates remain low, real estate bubbles tend to remain well supported.

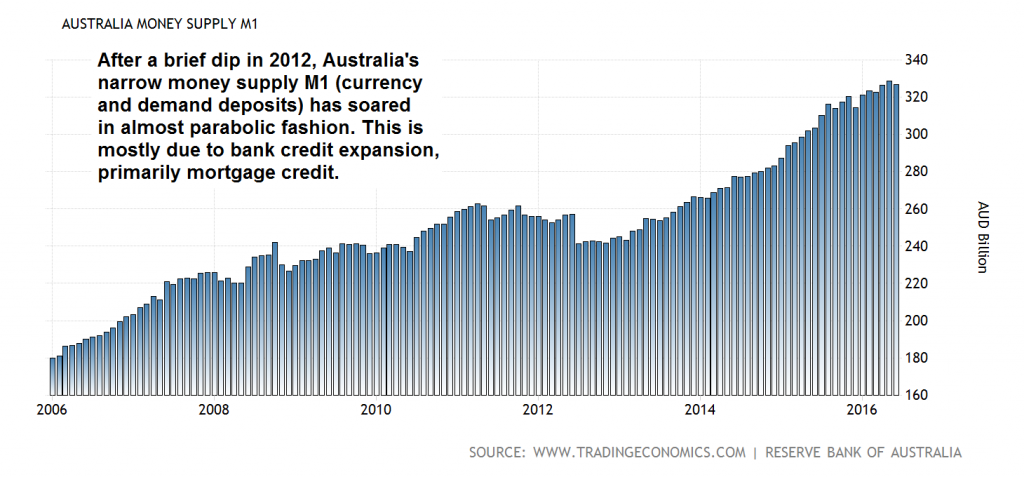

Let us not forget, the bursting of a number of housing bubbles in 2006-2009 (in the US, Spain and several other countries) was preceded by a slow but steady increase in interest rates and a sharp slowdown in money supply growth in the major currency areas. Neither one nor the other are in evidence in Australia at present – at least not yet. |

Australia Money Supply M1 |

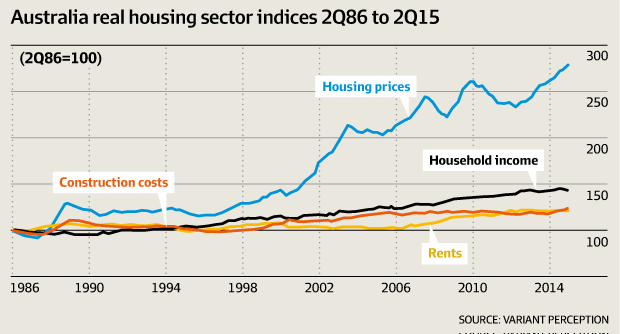

An Important New DevelopmentOne of the reasons why interest rates are so important in keeping residential real estate bubbles from imploding is that they make otherwise unaffordable properties seemingly affordable. Most home buyers use mortgages to finance house purchases, and the size of the monthly payment is therefore a main criterion in terms of affordability. Given that these are usually very long term loans with terms ranging from 15 to 30 years, the level of interest rates makes an enormous difference. Below is a slightly dated chart via Variant Perception (ending in Q2 2015) that compares Australian home prices, household incomes, rents and construction costs. It should be obvious how irrational house prices have become in light of the huge gap that has opened up between these time series. The chart also demonstrates that low interest rates are indeed of overwhelming importance in sustaining these sky-high prices. There is certainly little else that will. |

Australia House Prices vs Income |

| Keep in mind though what we have mentioned in the annotation to the chart of Australia’s money supply above. The credit expansion that has been the driving force of the bubble has largely been the work of commercial banks. While the central bank has enabled them to offer loans at lower and lower rates, it is their willingness to actually do so that is decisive.

One of our readers has recently made us aware of a recent development that may well throw a major spanner into the works. Similar to what has happened in other desirable destinations, Chinese buyers have played an increasingly important role in Australia’s property market. They have been especially active in the market for condominiums, which has experienced an extremely pronounced boom as a result. What we were hitherto not aware of was the extent to which these buyers have actually obtained financing from Australian banks. This source of funding is now threatening to dry up. The banks are pulling back after learning that many of the loan applications seem to be fraudulent. This happens to coincide with a noticeable surge in supply in the market – many developments that have been started in order to cash in on the huge gap between prices and construction costs are now finished or about to be finished (we can picture a great many “ghost apartment blocs” in Australia’s future). |

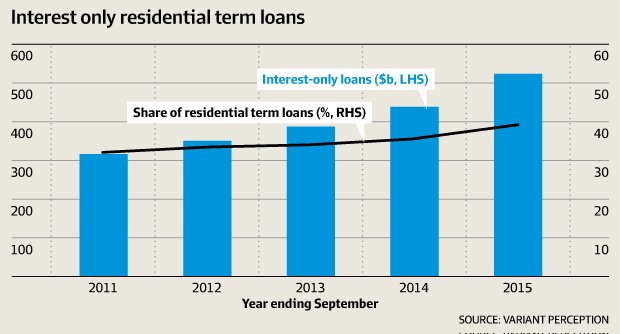

Interest only loansAnother chart illustrating the importance of interest rates to Australia’s housing bubble: the share of “interest only” mortgage loans, the principal of which is settled with a balloon payment at the end of their term. The influence of rates on the size of the monthly payment is even greater in these cases. |

As the Financial Review reports:

“Off-the-plan buyers of Australian apartments are in crisis as tough new borrowing rules mean thousands of investors who have paid a deposit are struggling to complete their purchases, according to local and overseas mortgage brokers and financiers.

Shanghai-based financiers claim their Chinese clients’ funding from Australian banks has been frozen and they face foreclosure – or usurious interest rates – from private financiers. Australian financiers claim their local clients, many of them Asian, have had their settlements deferred by three months to find alternative funding.

“All the deals have been frozen,” said Mark Yin, an agent with Shanghai-based Home Tree Group, about his Shanghai clients’ funding with Australian banks. “We are now looking for finance all over the world.”

Mr Yin said this represented nearly 100 per cent of his clients who were waiting for properties to be completed in Australia and that most of the apartments were in the Melbourne CBD.

Melbourne-based Marshall Condon, chief executive of mortgage broker Neue Black and who also has off-shore and local Asian investors, added: “In the next three to 12 months, many investors will be applying for funding to complete their deals, however, they will be become increasingly concerned as they discover funding is limited.”

Billions of dollars has been invested in tens-of-thousands of high-rise apartments that are reshaping the skylines of the nation’s major capitals, particularly Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. Most have been sold off-the-plan, which means purchasers buy off the blueprint with a deposit and complete when it is built, which requires a second valuation and financing commitment by the lender. But a huge increase in supply has slowed demand, particularly around Melbourne’s CBD, pushing down prices.

Lenders, which initially fell over themselves to finance overseas’ buyers, slammed on the breaks when spot checks on the loan applications detected widespread fraud. The main problem is mainland Chinese buyers, which account for about half of the deals. That means many local lenders that agreed to provide funding when buyers made deposits, will not recommit upon completion.

Nervous local lenders fear that a sharp downturn, or change of sentiment, could result in foreclosures with overseas borrowers they have little chance of locating. Mortgage brokers, who receive their commissions upon final completion, are nervous they will not be paid for negotiating deals and financing.

Developers, some of whom have already canceled projects, are concerned about financing existing and future projects. It also has potentially big economic impact for local consumer sentiment, building services and government revenues.

Overseas financiers, typically based in Singapore and Malaysia, are working on rescue packages for borrowers by creating private bail-out funds, or buying apartments off stressed purchases, which means they lose their deposit. They include rolling five-year terms, starting at 7.5 per cent, or one-year emergency loans at 12 per cent, according to financiers.

Other packages are stepped-loans where the different amounts of the loan have different rates, invariably several times higher than Australian lenders’ standard variable or fixed rate loans. For example, Australian banks and other local lenders are offering three-year fixed rates at below 4 per cent. Home Tree Group’s Mr Yin said so far he was unable to secure funding for his clients and doubted they would be able to settle.

“I have now stopped dealing in Australian property,” he said. Another agent in Shanghai, the chief executives of Iron Fish China Lanny Xu, said while most of his clients were not affected by the change, around 20 per cent were trying to on-sell apartments as they were unable to complete settlement.

He said of some were looking to banks in Singapore for financing, as they were still happy to extend loans over Australian property. “The cost of funding in Singapore is higher than in Australia,” he said.

Mr Xu said another option was to seek finance from newly established mortgage funds, which were looking to fill the gap left by the withdrawal of Australian banks from the market. He said such funds were charging interest rates of between 8 per cent and 12 per cent.

Scott Kirchner, the manager of Bella Resident in China, said the inability of offshore buyers to access finance was “really starting to bite”. “We are reluctant to take on new clients unless they have 100 per cent of the cash for a property,” he said. “But then there’s the issue of how do they get the money out of China.”

Condominium high-rises in Melbourne – to date the consensus was that the market “might” be oversupplied by 2018 – it appears as though this juncture has been brought forward. Photo credit: Angela Wylie - Click to enlarge

(emphasis added)

In other words, a number of buyers are now faced with a sudden increase in interest rates from 4% to between 8% to 12% – regardless of the administered interest rate of the RBA. It is of course possible that the effect will once again stay local (i.e., confined to Melbourne and condominiums), similar to what happened when commodity prices collapsed.

The downturn in commodities led to sharp declines in property prices in regions and towns close to mining activities. However, house prices in the big cities continued to soar – not least because the RBA cut rates in order to offset the impact of the commodities bust.

It is definitely possible though that this latest development is actually the pin that finally pricks the bubble. As noted above, in Kuwait a single bounced check reportedly triggered an avalanche. The Souk Al-Manakh bubble is certainly not directly comparable to Australia’s housing market, but when a bubble is already very stretched, something will eventually trigger its demise – at times it can even be a seemingly small event.

Conclusion

It is a very good bet that many of the condominium high-rises built in anticipation of ever-growing demand and an unimpeded expansion of bank credit will turn out to have been unwise investments. As Ludwig von Mises reminds us in Human Action, these malinvestments become visible once the banks are getting cold feet and are beginning to pull back – which is precisely what seems to be happening in this case.

However conditions may be, it is certain that no manipulations of the banks can provide the economic system with capital goods. What is needed for a sound expansion of production is additional capital goods, not money or fiduciary media. The boom is built on the sands of banknotes and deposits. It must collapse.

The breakdown appears as soon as the banks become frightened by the accelerated pace of the boom and begin to abstain from further expansion of credit. The boom could continue only as long as the banks were ready to grant freely all those credits which business needed for the execution of its excessive projects, utterly disagreeing with the red state of the supply of factors of production and the valuations of the consumers. These illusory plans, suggested by the falsification of business calculation as brought about by the cheap money policy, can be pushed forward only if new credits can be obtained at gross market rates which are artificially lowered below the height they would reach at an unhampered loan market. It is this margin that gives them the deceptive appearance of profitability. The change in the banks’ conduct does not create the crisis. It merely makes visible the havoc spread by the faults which business has committed in the boom period.

– L.v. Mises, Human Action p. 559

Bonus picture: the back of the $1 million shack. Just in case you thought it might look better from a different perspective… Photo credit: Attila Szilvasi - Click to enlarge

(emphasis added)

It is probably still fair to say though that an outbreak of caution on the part of lenders is a trigger for the bust, in the sense that the illusory accounting profits generated during the boom period will suddenly disappear.

Of course it remains to be seen if this recent development will have wider implications for Australia’s real estate bubble or if the central bank’s loose monetary policy will continue to trump such disturbances in the farce. This is one development though which the RBA cannot really influence – it is essentially a major rate hike affecting an important group of buyers, and it seems as though a lot of hitherto anticipated demand simply won’t be there.

Charts by: TradingEconomics, Variant Perception