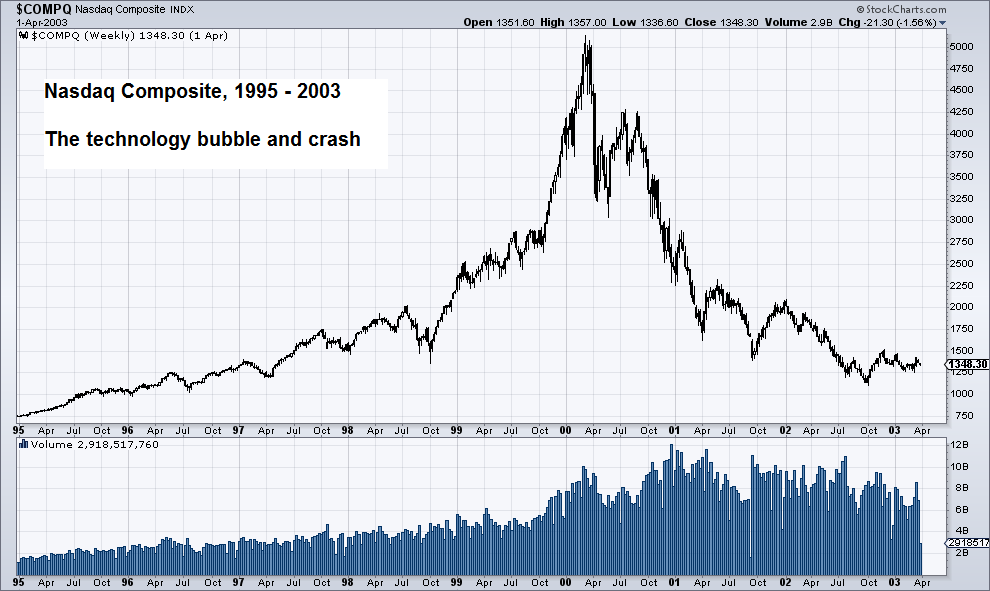

The Wild 1990s Not so long ago, during 1990’s, the connecting world of the connected world we now know was literally and comprehensively in the development stage during those wild crazy go go years before the crash in technology stocks in 2000. Nasdaq Composite, 1995 – 2003, The technology bubble and crash The infamous tech bubble of the 1990s – to this day the greatest stock market bubble ever seen in the US (in terms of multiple expansion, intensity, public participation, speed and extent of the blow-off phase) – click to enlarge. Nasdaq Composite, 1995 – 2003, The technology bubble and crash What you saw on your monitor then, really was more or less what you got, depth hardly existed. Almost all internet services were flat and by subscription, billed by the minute. America Online, Prodigy, Compuserve, and thousands of “bulletin boards” for online exchanges, information posting, questions and answers, were the destinations. Little if anything was recorded though perhaps in AOL’s more risqué “chat rooms” (the original Skype) a live monitor (actually a volunteer for reduced fees) might be listening in, which is to say, “reading in”. There was no voice over internet protocol then, no recording machines or capture software and no video. Modern data storage was in its infancy, even if the intention to record all data already existed.

Topics:

E. F. Vidocq considers the following as important: Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, Human Condition, newsletter, On Economy, On Politics

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The Wild 1990s

Not so long ago, during 1990’s, the connecting world of the connected world we now know was literally and comprehensively in the development stage during those wild crazy go go years before the crash in technology stocks in 2000.

Nasdaq Composite, 1995 – 2003, The technology bubble and crashThe infamous tech bubble of the 1990s – to this day the greatest stock market bubble ever seen in the US (in terms of multiple expansion, intensity, public participation, speed and extent of the blow-off phase) – click to enlarge. |

What you saw on your monitor then, really was more or less what you got, depth hardly existed. Almost all internet services were flat and by subscription, billed by the minute. America Online, Prodigy, Compuserve, and thousands of “bulletin boards” for online exchanges, information posting, questions and answers, were the destinations.

Little if anything was recorded though perhaps in AOL’s more risqué “chat rooms” (the original Skype) a live monitor (actually a volunteer for reduced fees) might be listening in, which is to say, “reading in”. There was no voice over internet protocol then, no recording machines or capture software and no video.

Modern data storage was in its infancy, even if the intention to record all data already existed. The subscription model, the “dial in” model via modem to telephone numbers in as many cities as an expanding provider might locate equipment, was the market.

The telephone companies themselves played no major role per se in the interface other than over their wires. They received no extra fees above and beyond their simple per call rates. They had not yet, as they used to say, “intermediated”, or today, found a way to “disrupt” and/or “hack” into, the business model.

There was then endless discussion about how or who would transform the old pairs of twisted copper wires into carriers of enormous numbers of signals (data), never imagined when the telephone network infrastructure was created, and how to avoid completely rebuilding it.

The grab and quest for the dominant solution was expressed in the many nearly instant failures and successes of hundreds of companies along the development paths taken to our present day.

Bibles were being written and internet gurus roamed the planet; Mary Meeker of Morgan Stanley, the Empress of technology stock picking or Geoffry Moore’s best selling Inside the Tornado and Crossing the Chasm, the strategy books for how to become a “Gorilla”.

Few investors actually knew anything substantial about these companies in any real way, including the gangs of research analysts, Fidelity Fund managers, let alone so called retail investors, i.e. those not working for an investment house, but now, via the internet, with their own direct trading accounts at places like National Discount and Lombard; live, in person, desk brokers all but eliminated and dis-intermediated.

Investment houses began hiring technologists from places like MSFT and hardware companies like SUN or CSCO, paying them enormous sums of money to explain the all of it, while the street analysts roamed the back halls at investor conferences and trade fairs seeking the pre-earnings edge.

Insider information, rumor, and outright stock promotion ruled the day along side NAV projections that were so forward looking it might take 100 years for that company, if it still existed, to reach par with the numbers. Go-go days indeed! People were running as fast as their greed and margin accounts would allow, including all of the major investment houses.

Chasing the Next Big Thing

Computer Associates was an example of how that worked. It held its earnings conference amid the luxurious and tightly controlled confines of the Waldorf Astoria hotel. Only handpicked analysts were invited to these meetings, and selectively, if you could acquire the telephone call-in code, other analysts from out of town would be listening in by conference call.

During one such occasion, I clearly remember Sanjay Kumar explaining, with amazing clarity, how CA was cooking its books to make the earnings numbers, though he did not use those words. They were forward booking their sales. In those days the FASB cared about accounting irregularities, so his boldness seemed rather shocking to me at the time. It took another year or two before Sanjay was tried and convicted for a 2.2 billion dollar fraud.

Sanjay Kumar (center), here seen accompanied by his lawyers. He was eventually sentenced to 12 years imprisonment Photo credit: Patrick Andrade / NYT

Yet, during the call, not a single high powered analyst asked any questions, nor were there any downgrades in their ratings of the company, or the numbers they used to validate their forecasts. A lot of money was made on the pure thin air of Sanjay Kumar’s numbers. And then lost. Everyone happily drank Sanjay’s Kool-aid.

What we see today, could not have been possible without tremendous innovation in the housing (storage) and distribution (serving) of data. The entire concept of taking, for example, a once paper file filled with documents of varying kinds, and transforming it into a digital real time on-demand complex record-set was a key problem to solve before anything like Google, Facebook or the current intelligence agencies of the 5 Eyes Nations might come into existence.

What data there was, like IRS records or banking records, were flat, one dimensional, barely relational, not multi-dimensional. Data without broader context, viewable only in the most narrow of ways, a colorless dot matrix world.

In this field there was a great war between the likes of Sybase, Informix, Oracle, IBM, and MSFT, among others. Share prices were key to the success or failure of their efforts, as important as the technology itself, and a company’s ability to claim market share and retain pole position in the race to dominance, as well as keep the designing talent happy via the corporate version of money printing; i.e. stock options. Favored analysts were given special attentions to help equity investors “understand”.

To be short anything was somewhat a fool’s game. The game was to be long the “right” technology horse, be it the little needle maker Innovex (for data writing inside hard drives) to Worldcom and its glass fibers. Beating the number, hyping the story, selling dominance, talking up the “killer solution”, were the first orders of business.

Let the long term take care of itself, a place you’ll not ever see without first conjuring the “wave” and riding it like the gyrations of a wild bronco to at least some great fortune making crest.

Do that, and you get to be a venture capitalist during your next career, picking and funding the next big thing, or as they say today, “Unicorns”. Free zero interest money, chasing unicorns and 100 million dollar art, while the bills continue to pile up around the world, unpaid, until Peter comes knocking on Paul’s door, asking for his money back.

A Memorable Trade Show

Around 1996 one of the first “internet-centric” trade shows was held inside the Javits Center in New York City. The bigger the booth, the larger and more powerful company inside it. IBM was large; Microsoft was Gigantic. Like minions at the service of a king, smaller booths surrounded the edges of these courts, small suitors with big dreams, allied technologies tethered in part to the mother ship.

In other corners of the hall, the back aisles, small independents with no particular affiliations or known “adoption rates” for their products, stood by their single lap tops and meager hand-outs hoping to demonstrate to just the right attendee the potential of their product.

The early forerunner, to the now ubiquitous voice inside most automobiles today, giving directions via GPS locators and built-in moving digital maps, or portable Garmin-like devices, had just such a booth; Mapquest.

This was a very big day for Informix. Their booth was positioned not far away from the main concourse, but in a way to showcase itself. Chairs were placed inside a kind of mini auditorium created from a large tent where every thirty minutes a host of actors would roll out before the crowd a demonstration of the Universal Server. The tent was packed, and lines formed for each show which might have been standing room only, if standing had been allowed. Undivided attention by design.

Today we take for granted, when there is an accident, the insurance adjustor arrives at the body shop to approve the claim for repairs. On his lap top, there might be a picture of the car, data showing the car’s history, data about the insurance policy, data showing if the premiums have been paid, data about the service history (older accrued data) tied to the vehicle’s identification number, data about annual inspections, current data about the car’s actual market value, the credit history of the car’s owner and history of any prior accidents or driving infractions…

All of these data sets being both unique, but at the same time related, all arriving from some distant storage place independently but at the right time to a single page or two on the adjustor’s computer screen. Informix was claiming victory for the best solution to the comprehensive delivery of relational data from broad nominally disparate categories housed in varying depositories either on data reels or banks of hard drives.

In 1997, Informix hit a major speed bump and was forced to restate several years of earnings. Its then CEO Phillip White was eventually indicted by a federal jury on eight counts of securities, wire, and mail fraud. The charges were vastly reduced under a plea bargain in 2004 and White got off relatively lightly. Informix was eventually bought out by IBM.

In 1997, Informix hit a major speed bump and was forced to restate several years of earnings. Its then CEO Phillip White was eventually indicted by a federal jury on eight counts of securities, wire, and mail fraud. The charges were vastly reduced under a plea bargain in 2004 and White got off relatively lightly. Informix was eventually bought out by IBM.

It was a very impressive presentation and one might wonder how many weeks the presenters had practiced their pitch. It was so flawless, audience questions were never really answered; they, the audience had fallen in love, were desperate to love, and thereby their questions were easily diverted.

The “roll out” was so perfectly executed, a suspicious analyst might well wonder if it were some kind of 3-card Monte being played on the streets outside, or a deftly demonstrated shell game. How to know, however, probably was or would be a nearly impossible task, and certainly not answerable at the Javits Center that day.

In the weeks prior to the IFMX roll out, I had acquired a very large position in IFMX shares, and the market for them was trading with me, which is to say, UP. My interest at the show therefore was not just casual. On my way to leaving the exhibition, I just happened to walk by the Microsoft “court”, and there on the back aisle was a tiny little booth with a single printed sign that said Informix.

There a lone Informix engineer, middle aged, somewhat tired looking was standing by himself. Nobody was stopping by his booth. I thought, isn’t that strange. The biggest product roll out in his company’s history taking place a few hundred feet away, and here he is, all by himself, virtually friendless.

So I walked up and congratulated him on his company’s great news, and told him how “wow’ed” the crowd was during the demonstration. I really thought he was going to cry. He said virtually nothing to me in response to my excited comments.

On the strength of that accidental meeting, I stopped at the row of phones outside the great hall and sold all of my shares on the way out. Not too long after, and recounted now on Wikipedia, the air went out of this technology Balloon Dog in the form of 100’s of millions of dollars:

Corporate misgovernance overshadowed Informix’s technical successes. On April 1, 1997, Informix announced that first quarter revenues fell short of expectations by $100 million. CEO Phillip White blamed the shortfall on a loss of focus on the core database business while devoting too many resources to object-relational technology [Universal Server, editor’s note]… Informix re-stated earnings from 1994 through 1996. A significant amount of revenue from the mid-1990s involved software license sales to partners who did not sell through to an end-user customer; this and other irregularities led to overstating revenue by over $200 million. Even after White’s departure in July, 1997, the company continued to struggle with accounting practices, re-stating earnings again in early 1998.

I would happily write that engineer a check or hand him some kind of gift, were I ever to find him again. If there is one word to describe the technology crash, and ultimately, the greater markets crashing in 2000, that one word would be TRUST.

Short on TruSt

In our world today, that single word or the value of it, is being challenged across the entire economic landscape. The challenge to it has been created by the indifferent, bad, and also very willful behaviors, if not in some quarters incompetence, of the very same people, businesses, quasi government and government organizations a lack of trust will bring down.

When suspicion, fear, disgust, and revulsion (dare we add the word rebellion) replace trust to a degree that impacts not only their business models, and the structures of government as well, including the plethora of crony relationships that have, during these last two decades, reinforced them, it will be time to short this bubble too, though undoubtedly with great care.

When the bubble of data capture in every corner of daily life loses whatever its originally perceived benefit was, or conversely, when those who capture it become morally less credible while the mass user/provider population becomes less credulous and more apt to avoid membership in the Jonestown worship of all things data, the change will be, dramatic, and if not immediately a business opportunity for its replacement, then at least an invitation to taking advantage of any selling that may ensue.

The list grows every day and reaches every corner now of our current iteration of a connected, networked world, of those companies, their products, and their clever services who are not worthy nor or they worth the trust of their customers:

Juniper Networks, whose source code and the privacy their products provide, has been perverted either intentionally, incompetently and naively, or by infiltration of a 5 Eyes agency.

A Samsung television set that broadcasts back to its maker all things it hears in the living rooms of its customers. A show of willful pre-calculation without a plan, but symptomatic of the data gathering mania at hand.

Windows 10 hoovers up its users’ data in the most broad capture of individual computer use ever, transmitting all back to MSFT’s data center in Redmond, Washington USA. Their entire company history knows few bounds when it comes to questionable morality; it is well ingrained into its corporate character.

These are just three examples of products paid for by their customers who most likely do not and did not realize what they bought, is not what they paid for, including their assumptions about ownership and privacy.

Those, however, are not part of the free-to-use handshake the other providers of services use to explain their abuses of user privacy. An assumption seems to have developed in business and government today that privacy (all of its definitions) has no value of its own, and is up for grabs.

Some people however, are now asking what value is privacy worth, and were it to be re-established along the old pre-data capture boundaries, how would those companies, which are so reliant upon its absence, fare. Potentially, not well at all.

Meanwhile, congressmen and parliamentarians of the West on behalf of the security services they no longer control, consider passing laws requiring a back door to every private digital space without giving it a single thought they will with an incredible lack of understanding, by law, enshrine and certify all connected and connecting things made in the United States as hazardous to the privacy health of every individual and business using them.

That might be fine for their USA based citizens and customers who generally seem without a care. But all who live in the real world outside of the United States have clearly started looking for alternative solutions.

Regarding those “free” services, which absolutely do not protect the unique identifiers of their users, and which say they will do “no evil”, and yet they do remarkable evil, we’ll leave you with the words of Mr. Zuckerberg of Facebook who, because he says he’s older now, should not be held to account for the digitally captured record of his words, his true unabashed feelings about those who subscribe to his concept of socializing and who form the core of his business:

ZUCK: Yeah, so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard

ZUCK: Just ask

ZUCK: I have over 4000 emails, pictures, addresses, SNS [social security numbers, ed note]

FRIEND: What!? how’d you manage that one?

ZUCK: People just submitted it

ZUCK: I don’t know why

ZUCK: They “trust me”

ZUCK: Dumb fucks

(Source: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/20/the-face-of-facebook) May 13, 2010)

[A special thanks to Mr. Robert Blumen and for his time discussing some of the themes outlined in this article]

This article was originally published in Dr. Marc Faber’s “Gloom Boom and Doom” report and is reprinted with permission

Chart by: StockCharts, chart and image captions by PT

Previous post Next post