Risk markets where there is room to loosen policy but are undervalued look more attractive than those where the authorities have room to manoeuvre but markets are expensiveAt this mature stage of the business cycle, it makes sense to consider the possible next steps in economic policy, given that we believe it is likely that central banks and governments will do their utmost to prop up the bull equity market as well as economic growth. (This will be especially true in the US as the 2020 presidential election looms into view).Given that interest rates are already at historic lows and accumulated debt is high, there does not seem to be much room for the authorities to loosen policy further. However, the situation varies from country to country. According to our analysis, countries like

Topics:

Christophe Donay considers the following as important: Economic policy, Macroview, Market stimulus, Modern Monetary Theory

This could be interesting, too:

Monetary Metals writes Ep 52 – Jeff Snider: Solving the Eurodollar Puzzle

Claudio Grass writes The importance of being modest

Claudio Grass writes The importance of being modest

Dirk Niepelt writes Lucas on an OECD Economic Expert Report

Risk markets where there is room to loosen policy but are undervalued look more attractive than those where the authorities have room to manoeuvre but markets are expensive

At this mature stage of the business cycle, it makes sense to consider the possible next steps in economic policy, given that we believe it is likely that central banks and governments will do their utmost to prop up the bull equity market as well as economic growth. (This will be especially true in the US as the 2020 presidential election looms into view).

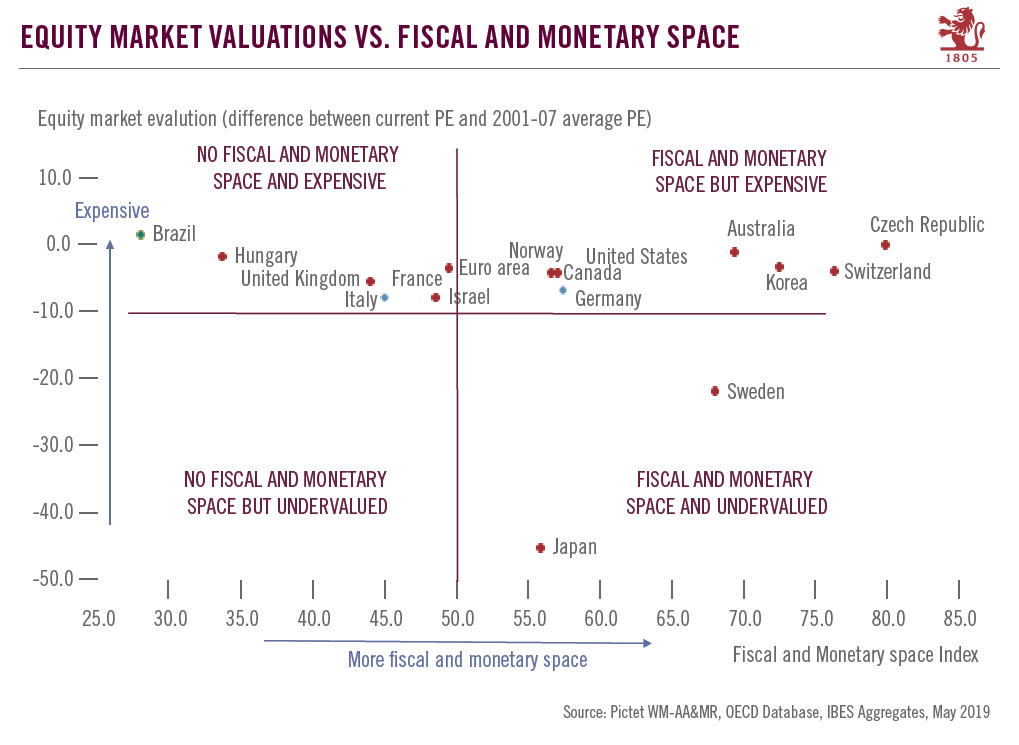

Given that interest rates are already at historic lows and accumulated debt is high, there does not seem to be much room for the authorities to loosen policy further. However, the situation varies from country to country. According to our analysis, countries like Switzerland, Korea and Czech Republic still have both fiscal and monetary space (in other words, nominal interest rates are below their historic average and the public debt-to-GDP ratio is below 60%). Others (the US, Canada, the UK, France) still have monetary space, but limited fiscal space, while Brazil and Hungary would appear to have neither fiscal nor monetary room to stimulate their economies.

In the case of the US, while the Trump tax cuts at the end of 2017 have left public finances stressed, economic growth has been better than in most of the developed world and unemployment is below 4%. This situation has given rise to the debate around modern monetary theory (MMT), which posits that since currency remains a public monopoly and since the US is able to borrow in its own currency, government deficits do not matter. In these circumstances, fiscal policy should take the lead in managing inflation and the economy rather than monetary policy. The proponents of MMT argue that changes to taxes and spending impact the economy faster and more predictably than rate policy. They may have a point: given the low level of rates, a fresh dose of negative interest rates and quantitative easing may not prove all that effective once a new recession strikes.

While MMT is not necessarily the only alternative, differences in the scope for public stimulus could have an impact on market trends, especially for equities. Comparing price earnings ratios for various markets with our Fiscal and Monetary Index (FMI), which calculates countries’ fiscal and monetary space combined (see chart), one sees that Japan and Sweden have both policy space and equity market valuations that are below their average for the period 2007-2017. But there are many more markets where, although there is still room to ease policy, equities are expensive, or at least fairly valued. And then there are markets (Brazil, Hungary, the UK, Italy, France) with very limited policy space where price-earnings ratios are high.

While the situation differs from one country to another, an approach to economic policy that combines monetary and fiscal measures in new ways could result in a further expansion in valuations and keep long-term interest rates low—especially as, for now, the golden rule is broken (in other words, the ‘rule’ that says that nominal rates should be close to nominal GDP growth).