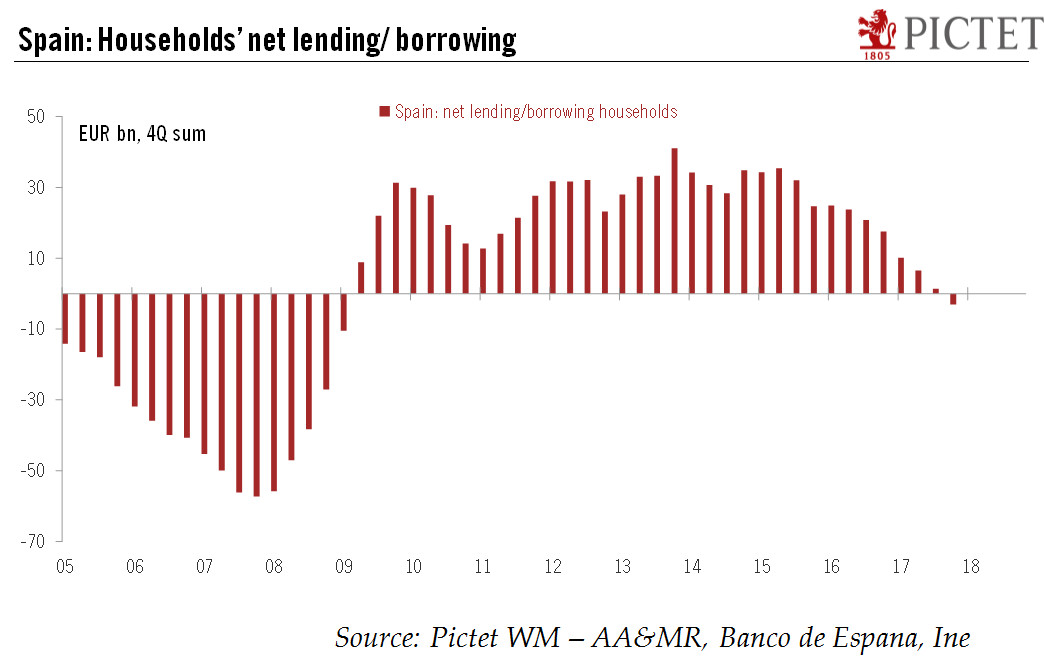

After years of frugality, Spanish households are re-leveraging again.Before the financial crisis, the real estate bubble and the parallel growth in borrowing meant that the indebtedness of Spanish households spiralled ever higher, reaching a peak of 84.7% of GDP in Q2 2010. Since then, Spanish’s households have tightened their belt, with indebtedness falling to 61.3% of GDP in Q4 2017.However, recent data suggest that the situation might be changing again. Indeed, in 2017, households borrowed net EUR3.1bn to finance spending. After years of saving, this was the first time since 2009 that families had net borrowings.There are several possible reasons for this turnaround last year. First, the improvement in Spain’s economic outlook could have made households more confident regarding higher

Topics:

Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Macroview, Spanish economic outlook, Spanish household consumption, Spanish household debt

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

After years of frugality, Spanish households are re-leveraging again.

Before the financial crisis, the real estate bubble and the parallel growth in borrowing meant that the indebtedness of Spanish households spiralled ever higher, reaching a peak of 84.7% of GDP in Q2 2010. Since then, Spanish’s households have tightened their belt, with indebtedness falling to 61.3% of GDP in Q4 2017.

However, recent data suggest that the situation might be changing again. Indeed, in 2017, households borrowed net EUR3.1bn to finance spending. After years of saving, this was the first time since 2009 that families had net borrowings.

There are several possible reasons for this turnaround last year. First, the improvement in Spain’s economic outlook could have made households more confident regarding higher incomes in the future. Second, record low interest rates and easy credit conditions might also have encouraged borrowing. Third, households finally made big purchases of durable goods such as automobiles and household appliances that they had been forced to postpone at the time of the crisis.

Linked to these developments is the low household savings rate. At the beginning of the financial crisis, the Spanish savings rate soared to its highest level since the launch of the euro area in 1999, reaching 13.4% of disposable income in 2009. But, it has since declined, and was equivalent to 5.7% of disposable income in 2017.