Investec Switzerland. Swiss National Bank President Thomas Jordan keeps saying the franc is “significantly overvalued.” And that’s despite the central bank’s record-low deposit rate and occasional currency market interventions. © Dariusz Kopestynski | Dreamstime.com While the franc is typically a top choice for foreign investors looking for a safe place to park their money, anxieties about the euro area’s debt burden or Brexit aren’t the only factor. The residents of Switzerland — which has a sizable current-account surplus despite its strong currency — are partly to blame because they aren’t moving money abroad, which could help them achieve higher returns. “Roughly speaking, about half the capital inflows are due to domestic investors, which means they’re contributing in a big way to the strength of the franc,” said Maxime Botteron, an economist at Credit Suisse in Zurich. The following four charts illustrate the state of play. Households have an ever-greater share of franc-denominated assets. It’s worth noting that the development of that ratio over time doesn’t factor in valuation effects due to changes in the exchange rate. Switzerland’s current-account surplus was nearly 11 percent of gross domestic domestic product at the end of March. That’s a ratio bigger than that of euro-area export powerhouse Germany and compares with a 5.

Topics:

Investec considers the following as important: Business & Economy, Editor's Choice, Strong Swiss Franc, Swiss Franc, Why Swiss franc is strong

This could be interesting, too:

Investec writes The global brands artificially inflating their prices on Swiss versions of their websites

Investec writes Swiss car insurance premiums going up in 2025

Investec writes The Swiss houses that must be demolished

Investec writes Swiss rent cuts possible following fall in reference rate

Swiss National Bank President Thomas Jordan keeps saying the franc is “significantly overvalued.” And that’s despite the central bank’s record-low deposit rate and occasional currency market interventions.

© Dariusz Kopestynski | Dreamstime.com

While the franc is typically a top choice for foreign investors looking for a safe place to park their money, anxieties about the euro area’s debt burden or Brexit aren’t the only factor. The residents of Switzerland — which has a sizable current-account surplus despite its strong currency — are partly to blame because they aren’t moving money abroad, which could help them achieve higher returns.

“Roughly speaking, about half the capital inflows are due to domestic investors, which means they’re contributing in a big way to the strength of the franc,” said Maxime Botteron, an economist at Credit Suisse in Zurich. The following four charts illustrate the state of play.

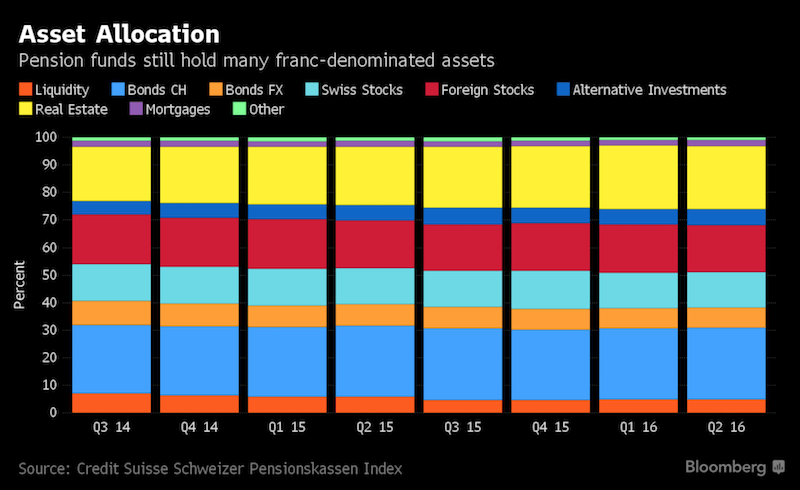

Households have an ever-greater share of franc-denominated assets. It’s worth noting that the development of that ratio over time doesn’t factor in valuation effects due to changes in the exchange rate.

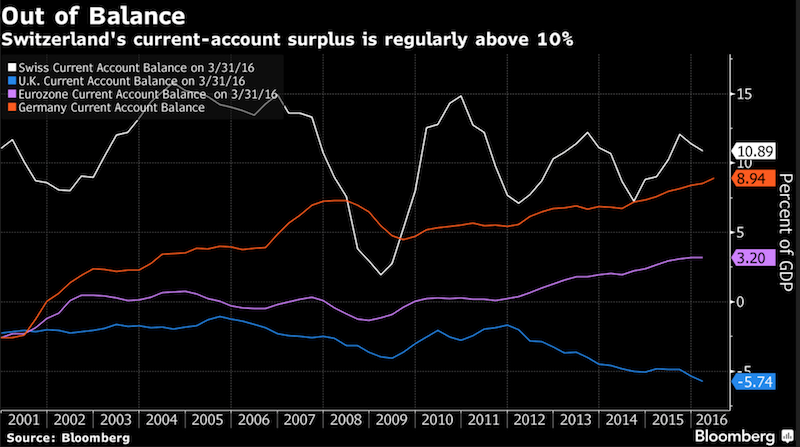

Switzerland’s current-account surplus was nearly 11 percent of gross domestic domestic product at the end of March. That’s a ratio bigger than that of euro-area export powerhouse Germany and compares with a 5.7 percent deficit in the U.K. The euro-zone average is a 3.2 percent surplus.

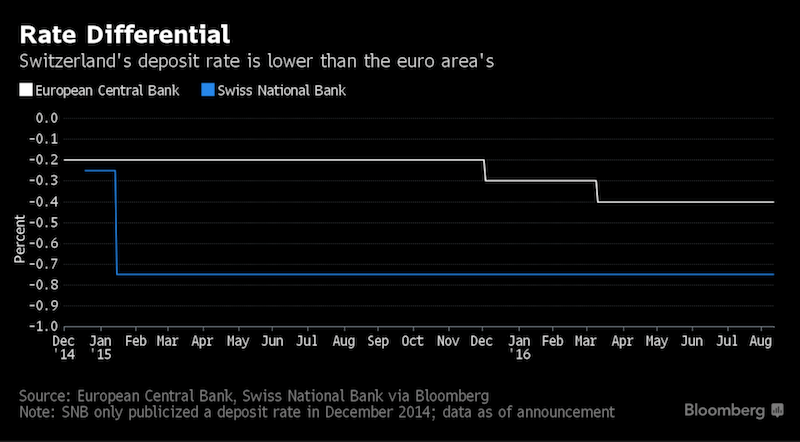

In a bid to drive down yields on franc-denominated assets, the SNB cut its deposit rate to a record low of minus 0.75 percent. Swiss policy makers have threatened to go even more negative if needed. Economists say investors won’t begin to hoard cash to circumvent the charge as long as the rate doesn’t fall below minus 1.25 percent.

Even with negative rates, Swiss pension funds hold the lion’s share of their assets in francs, according to a study by Credit Suisse. As in other jurisdictions, their investment decisions are affected by regulatory requirements.

If the Swiss themselves “were to invest more heavily in foreign assets, that could lessen pressure on the franc and the SNB wouldn’t have to intervene as heavily,” Botteron said. “But that probably would necessitate a change of policy in the euro area, with a widening of the interest-rate differential, which would make euro-denominated assets more attractive again.”

With economists anticipating further ECB stimulus rather than a cutback in stimulus, that doesn’t look to be happening any time soon.

By Catherine Bosley (Bloomberg)