JP Morgan’s CEO Jamie Dimon caused a stir yesterday with his 45-page annual letter to shareholders. The phrase that gained him so much widespread attention was, “there is something wrong with the US.” Dimon mentioned secular stagnation and correctly surmised it was the right idea if for the wrong reasons. He then gave his own which included a litany of globalist agenda items, including not enough access to mortgages. I agree fully with Mr. Dimon in those two respects, meaning first that there is surely “something” wrong that has caused a depression and second unlike economists he is right to suggest it isn’t a permanent condition. Getting that far, however, he stops short of going to the one place where irregularity is real and relevant – his own domain. Like Fed officials, there can be no accounting for money. This wasn’t always the case even from this particular bank CEO. One of the reasons this particular shareholder letter stands out is not just for its pessimism but more so the suddenness of it. Dimon has been almost unique in his positivity, suggesting that also like policymakers the “rising dollar” period finally convinced him of its folly.

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: balance sheet capacity, Banking, currencies, Derivatives, dollar shortage, economy, EuroDollar, Featured, Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, interest rate swaps, J.P. Morgan, Jamie Dimon, Markets, Monetary Policy, newslettersent, rising dollar kills the recovery (narrative), The United States, wholesale finance

This could be interesting, too:

investrends.ch writes «Wir stehen an der Spitze der Integration von Künstlicher Intelligenz»

investrends.ch writes J.P. Morgan mit aktiven ETFs auf Aktien und Anleihen von Schwellenländern

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

JP Morgan’s CEO Jamie Dimon caused a stir yesterday with his 45-page annual letter to shareholders. The phrase that gained him so much widespread attention was, “there is something wrong with the US.” Dimon mentioned secular stagnation and correctly surmised it was the right idea if for the wrong reasons. He then gave his own which included a litany of globalist agenda items, including not enough access to mortgages.

I agree fully with Mr. Dimon in those two respects, meaning first that there is surely “something” wrong that has caused a depression and second unlike economists he is right to suggest it isn’t a permanent condition. Getting that far, however, he stops short of going to the one place where irregularity is real and relevant – his own domain. Like Fed officials, there can be no accounting for money.

This wasn’t always the case even from this particular bank CEO. One of the reasons this particular shareholder letter stands out is not just for its pessimism but more so the suddenness of it. Dimon has been almost unique in his positivity, suggesting that also like policymakers the “rising dollar” period finally convinced him of its folly.

Back in October 2014, it was Jamie Dimon who bullishly stood on the American economy, though at that time it took no courage or insight to take such a position. Almost everyone was optimistic then even if most, including insiders and economists, really didn’t know why. The year was awash in confirmation bias as well as the circular, self-referential logic that so often goes with it: stock prices are rising because the economy is getting better, and the economy is getting better because stock prices are rising; the Fed thinks the recovery has arrived because banks think the recovery has arrived because Fed officials believe the recovery has arrived.

What Dimon said in 2014 was, “I’m a long-term bull on the US economy.” From that one statement you can understand the spotlight now on his current position which is the opposite of it. Secular stagnation or whatever you want to call it is at best low growth and opportunity as the basis or trend, a wholly unique condition for American economic experience outside of the Great Depression. Again, the “rising dollar” didn’t kill the recovery so much as so heavily damage the economy so as to kill the narrative of recovery.

In October 2014, however, there was one concern that Dimon did express, curiously one that seems left out of his current position.

However, he [Jamie Dimon] sees one thing that could derail the recovery: The $3.2 trillion ($15 trillion globally) nonbank financial system, or “shadow banks.”

…

However, asked what keeps him up at night, he said nonbank lending poses a danger “because no one is paying attention to it.” He said the system is “huge” and “growing.”

It’s actually not all that unusual that the CEO of JP Morgan would talk about “shadow banks” as if the term applied only to firms other than JP Morgan. I have no doubt that JPM’s management believes that their bank is a bank and not a full part of the shadow system. It is one reason, and a big one, why when discussing “dollars” it may seem like the “dollar” participants themselves appear to have no idea about it. One reason why the “shadow” system remains in the shadows is because everyone believes it only applies to some other guy.

| Beyond that, the shadows are much more than just lending and mortgages. From Dimon’s perspective, JP Morgan is out of that business, having divested itself and client money of things like the former SIV Sigma, the off-balance sheet conduits that funneled resources into the housing bubble. The shadow system, however, was not a singular, temporal quirk of an otherwise traditional banking system; it was a feature of the wholesale revolution that overthrew most banking dynamics. It’s a condition that decades after it intensified remains a mystery due to nothing more than uncorrected convention about money (and Positive Economics). |

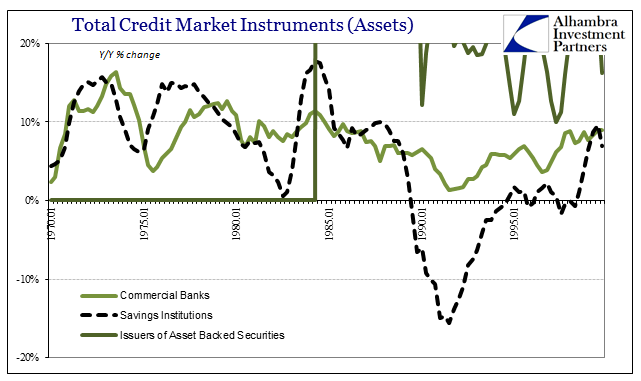

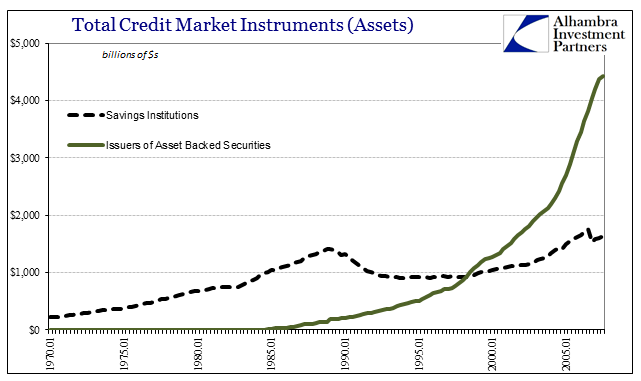

Total Credit Market Instruments |

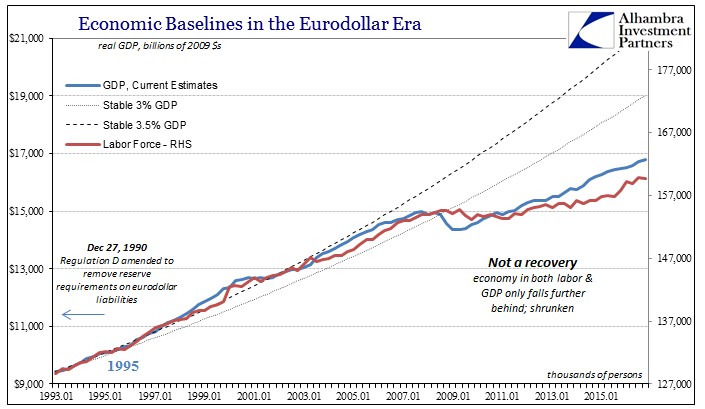

| The shadows remain our stagnation problem, for secular stagnation is truly eurodollar stagnation, but to which JP Morgan has played an enormous part. If we define shadow banking as only relating specifically to housing bubble era behavior, then Dimon would be correct to assume the global monetary problem is somebody else’s doing. There is so much more to it, as I discussed earlier today. |

Total Credit Market Instruments (Assets) from 1970 |

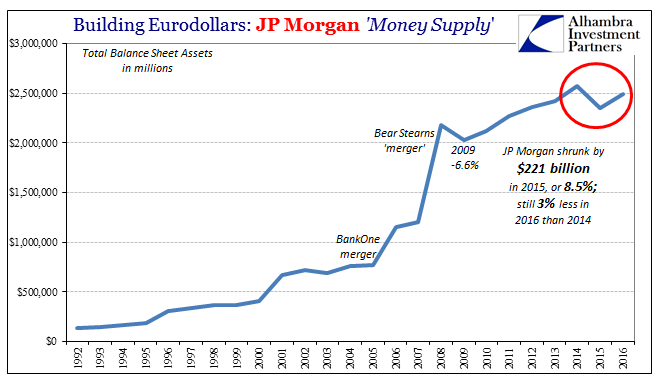

| Unlike some banks, JP Morgan’s balance sheet at least until 2014 was still growing, though at a much, much slower rate than during the precrisis period. During the past two years of the “rising dollar”, despite starting it with so much optimism, JPM’s balance sheet contracted sharply in 2015, more even than in 2009, and only partially rebounded in 2016. |

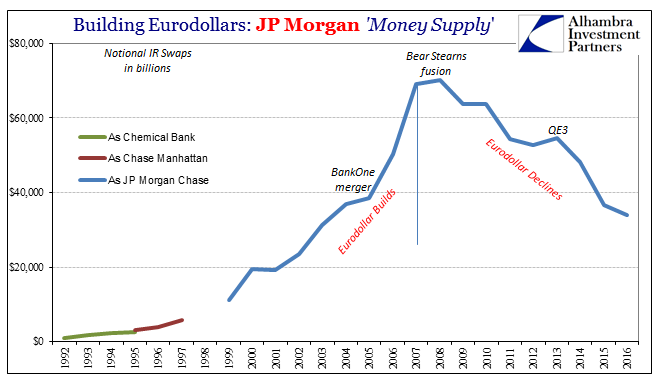

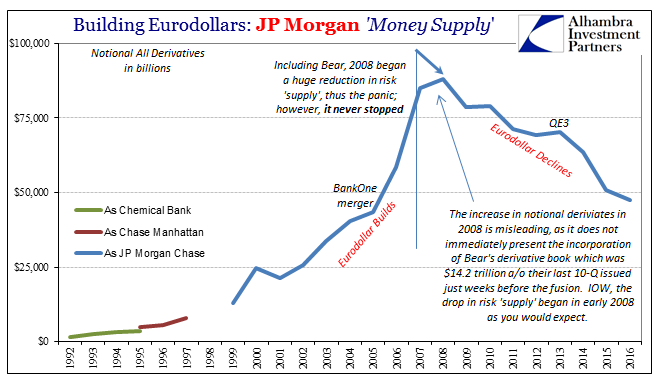

Building Eurodollars: JP Morgan Money Supply 1992-2017 |

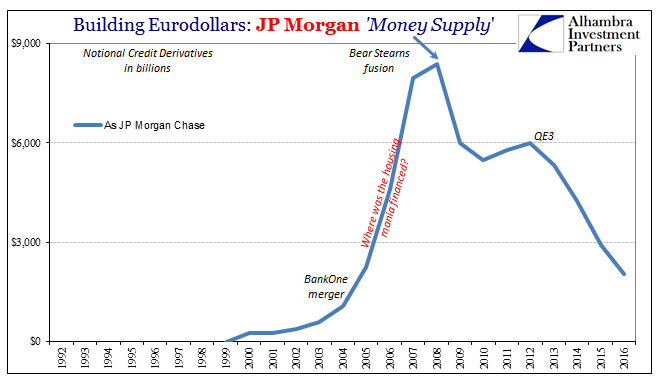

| In terms of the true guts of the eurodollar system, the fullest extent of the shadows, JPM has only been retreating and in the past few years severely – including 2016. |

Building Eurodollars: JP Morgan Money Supply 1992-2017 |

Building Eurodollars: JP Morgan Money Supply 1992-2017 |

|

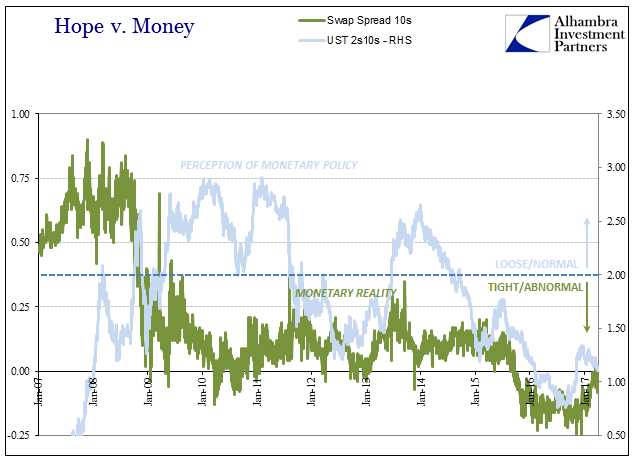

| The bank is but another anecdote for restricted balance sheet capacity matching up with the non-traditional monetary indications of “tightness” or even shortage. From the individual perspective of JP Morgan, what they are doing cutting back in risk capacity is mere prudence (risk v. reward), leaving it to the outside world, mostly the Federal Reserve, to deal with whatever total monetary issues. From the standpoint of traditional banking, JPM’s activities bear no resemblance to the “dollar shortage” or even the prospects for one. |

Hope v. Money 2007-2017 |

| It is what makes this problem so intractable, because the people closest to it don’t appear capable of grasping its true nature and thus the implications of what they do (and don’t do). It creates vast dissonance, where those inside the system claim there is nothing wrong with system so that a great many outside the system, especially in the media, simply accept the claim as unchallengeable. As such, “we” spend an entire decade looking everywhere else for answers.

Dimon’s October 2014 fears have been proved totally correct with but one exception – JP Morgan is not just a bank but a shadow player, too. |

Building Eurodollars: JP Morgan Money Supply 1992-2017 |

Economic Baselines In The Eurodollar Era 1993-2017 |

Tags: balance sheet capacity,Banking,currencies,Derivatives,dollar shortage,economy,EuroDollar,Featured,Federal Reserve,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,interest rate swaps,J.P. Morgan,Jamie Dimon,Markets,Monetary Policy,newslettersent,rising dollar kills the recovery (narrative),wholesale finance