Following the Swiss National Bank’s (SNB) publication of Switzerland’s balance of payments data for Q4 2017, in this note we look deeper into the Swiss current account to try to find out why Switzerland persistently runs a surplus and whether or not the current account balance can be used to assess the fair value of the Swiss franc. In 2017, the current account surplus stood at around 9.8% of GDP or CHF66bn. This was CHF4bn higher than in 2016. Persistent current account surplus can be explained by demographic trends, industrial structure as well as statistical distortions. As a result, the current account is far from a good proxy to value the Swiss franc. In recent years, international debate about countries’

Topics:

Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Featured, Macroview, newsletter, Pictet Macro Analysis, Swiss and European Macro, Swiss current account surplus, swiss franc valuation, Switzerland Balance of Payments, Switzerland surplus

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Following the Swiss National Bank’s (SNB) publication of Switzerland’s balance of payments data for Q4 2017, in this note we look deeper into the Swiss current account to try to find out why Switzerland persistently runs a surplus and whether or not the current account balance can be used to assess the fair value of the Swiss franc.

In 2017, the current account surplus stood at around 9.8% of GDP or CHF66bn. This was CHF4bn higher than in 2016. Persistent current account surplus can be explained by demographic trends, industrial structure as well as statistical distortions. As a result, the current account is far from a good proxy to value the Swiss franc.

In recent years, international debate about countries’ current account surpluses and unfair exchange rate policies has intensified. Against this backdrop, Switzerland has been on the US Treasury’s monitoring list since 2016, along with five other countries. While Switzerland does not meet all three of the US’s criteria to be considered a currency manipulator, it is being closely monitored by the US Treasury.

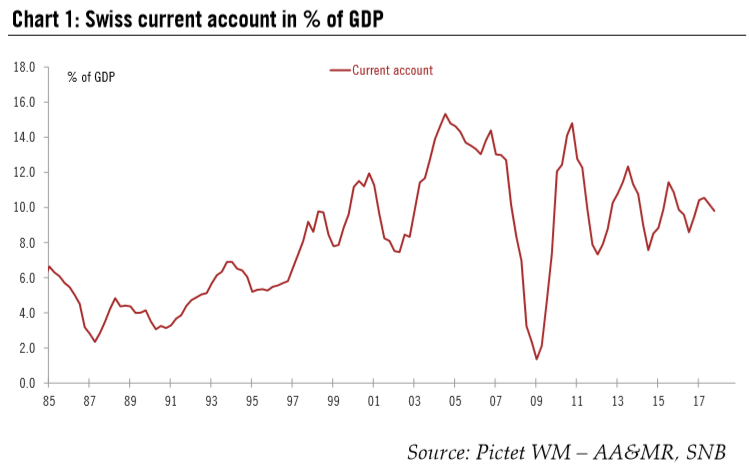

| A high current account surplus is not a new story for Switzerland as it has been running a surplus since the 1980s (see Chart 1). In simple terms, current account surplus means that the income received from non-residents exceeds the expenses paid to non-residents – or that Switzerland is saving more than it is investing domestically. |

Swiss Current Account in % of GDP, 1985 - 2018 |

Economic theory suggests that a large current account surplus is a function of an undervalued currency, as in order to restore a balance in future years the currency of a country running a surplus would need to appreciate, leading to a reduction in net exports. Based on this premise there could be some questions about the SNB’s monetary policy, as the central bank considers the Swiss franc as “overvalued” or, more recently, “highly valued” and has in fact been attempting to curb upward pressure on the currency.

Switzerland’s current account

Switzerland’s current account surplus increased sharply between 1990s and the onset of the financial crisis. It approached 15% of GDP in 2005, a level unsurpassed by any other country apart from Norway in OCDE history.

During the crisis, the current account surplus fluctuated significantly before stabilising at around 8–11% of GDP in recent years. However, Switzerland’s surplus is relatively insignificant on the global scale due to the small size of its economy.

Factors contributing to the persistent surplus in Switzerland

How can the persistent Swiss current account surplus be explained? In a speech last year, SNB President Thomas Jordan referred to structural factors and a number of statistical distortions that are contributory factors.

| 1) Industrial structure

Just two industries are in large part responsible for Switzerland’s trade surplus: pharmaceuticals (and chemicals) and merchanting. Switzerland has developed into a trading hub for commodities and raw materials, especially energy products and foodstuffs. The proceeds of this trade show up as merchanting trade1. While merchanting trade was relatively small at the beginning of the 2000s, it subsequently increased and stabilised during the crisis. Switzerland is not isolated in this respect; other countries such as Finland, Ireland and Sweden have also witnessed significant growth in merchanting. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical and chemical sector has gained in importance in terms of proportion of exports. While it accounted for under a quarter of exports in 1990, it made up 45% of total goods exports by 2017 (see Chart 2). Both the pharmaceuticals and merchanting sectors have grown strongly over the past decade despite the sharp appreciation of the Swiss franc. This is in contrast with the fortunes of other industries such as machinery and tourism, which are sensitive to the exchange rate and have suffered significantly as a result of the strong franc. Not only are pharmaceuticals and merchanting rather insensitive to FX changes, they have had a much greater impact on the development of the current account than on the Swiss economy. As Thomas Jordan has stated, this can be seen for example in terms of employment statistics: “The pharmaceutical industry and merchanting companies together employed approximately 50,000 people here in Switzerland in 2016. By contrast, the exchange-rate sensitive industries of other categories (see below) accounted for more than 325,000 employees”. |

Exports of Goods from Switzerland by Sector (% of total), 1990 - 2018 |

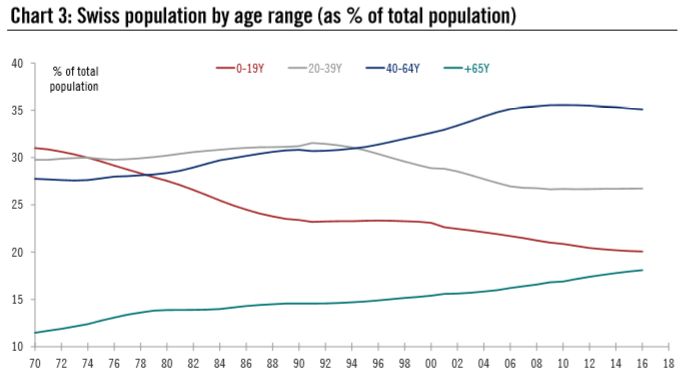

| 2) Demographic developments

Demography also plays an important role in explaining Switzerland’s current account surplus. Over 35% of the Swiss population is currently between 40 and 64 years old (see Chart 3). This is the age range with the highest propensity to save. What’s more, life expectancy has increased, meaning that it is now necessary to save more. |

Swiss Population by Age Range (as % of total population), 1970 - 2018 |

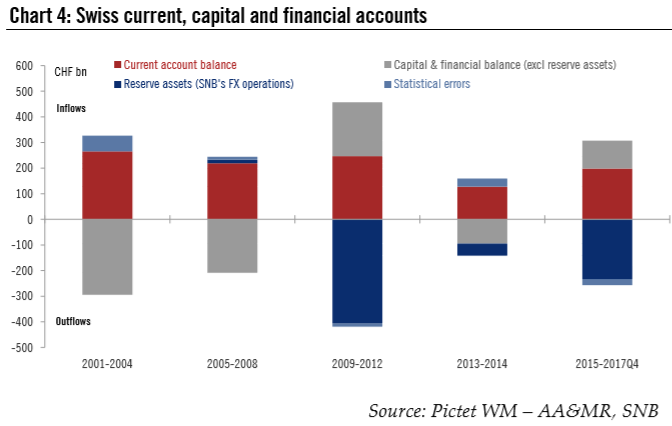

| 3) Statistical distortions

One way in which the surplus is distorted statistically is due to the ownership structure of listed multinational companies headquartered in Switzerland. A substantial percentage of these companies are held in free float by foreign investors. When these companies reinvest their profits, the profit is entirely attributed to Switzerland, even though it actually belongs to the foreign investors. As a result, this contributes to overstate Swiss current account surplus. The SNB and the balance of paymentSwitzerland’s financial accounts show how the country invests its current account surplus (foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, other investments and reserve assets). Swiss financial account composition has changed dramatically since the beginning of the financial crisis. Until 2008, Switzerland saw more outflows from the financial account, in both portfolio and foreign direct investments, meaning that the Swiss were investing more abroad than non-residents were investing in Switzerland (see Chart 4). This helped to offset the strong current account surplus. But with the 2008 financial crisis and the Eurozone crisis of 2011, the demand for Swiss-franc-denominated assets from non-residents and residents alike started to increase, leading to strong inflows. As a result, there was considerable upwards pressure on the value of the Swiss franc. The high inflows resulting from the financial crisis were, however, counterbalanced by an increase in reserve assets2. Indeed, the SNB bought large amounts of foreign currency, making a major contribution to the movements in the financial account balance and offsetting the current account surplus. |

Swiss Current, Capital and Financial Accounts, 2001 - 2018 |

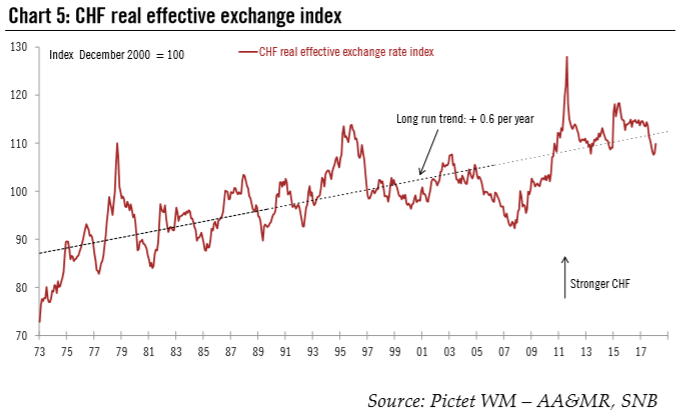

Is the SNB swimming against the tide?While economic theory suggests that a current account surplus is a function of an undervalued currency, for the reasons we gave above, the current account is far from a good proxy to value the Swiss franc. It is thus of little value for setting monetary policy. That being said, historically, the Swiss franc has displayed an upward secular trend (see Chart 5). Since the financial crisis, the SNB has geared its monetary policy towards easing pressure on the Swiss franc and making investments in Swiss francs less attractive by lowering its interest rate deeply into negative territory. Moreover, the SNB has countered any unwarranted appreciation of the Swiss franc by intervening in the foreign exchange market. According to its annual report, the SNB bought a total of CHF 86.1bn of assets in 2015, CHF 67.1bn in 2016 and CHF 48.2bn last year. Since mid-2017, SNB’s life has become somewhat easier. Euro area growth has picked up and European political instability has decreased somewhat, at least the probability of a euro area breakup has dropped. Nevertheless, the SNB is likely to remain cautious and stick to its two pillar strategy (namely negative interest rate and its willingness to intervene in the FX market if needed) in the near term. Importantly, the SNB will keep Swiss interest rate below ECB’s deposit rate, to make investments in Swiss francs less attractive and thus avoid putting additional upward pressure on the Swiss franc. |

CHF Real Effective Exchange Index, 1973 - 2018 |

Tags: Featured,Macroview,newsletter,Swiss current account surplus,swiss franc valuation,Switzerland Balance of Payments,Switzerland surplus