Jeff Gundlach is not the only person who is feeling “maximum negative” on Treasuries. In an interview, none other than the “Maestro” Alan Greenspan, the man whose “great moderation” policy made the current global bond bubble possible, said that he is worried bond prices have risen too high. Asked if he finds what is happened in the bond market right now “in any way, shape, or form concerning for financial stability”, Greenspan replied that “it’s obvious that you ought to be looking at the price earnings ratio in bonds to income. We get very nervous when the stock price index goes to high PE. We ought to be somewhat nervous when the bond rate does the same…. To believe that we can keep rates down here for very much longer strikes me as to say that human nature is going to change, and that’s one thing I wouldn’t bet on.” He did not mention that the only reason why there continues to be such an unprecedented stampede into fixed income, pushing yields to record (negative) lows, is because investors are merely frontrunning central banks; they also know that as monetization accelerates and as private supply leave the market, the same central banks will purchase whatever bonds they can find at any price, and that is the only reason why global bond yields are where they are.

Topics:

Alan Greenspan considers the following as important: Alan Greenspan, Bond yield, Central Banks, CHF FX, Featured, fixed, Global Economy, Gundlach, Jeff Gundlach, Monetization, Money Supply, newsletter, None, Price/Earnings Ratio, Recession, stagflation, Swiss Franc, Volatility

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

In an interview, none other than the “Maestro” Alan Greenspan, the man whose “great moderation” policy made the current global bond bubble possible, said that he is worried bond prices have risen too high.

Asked if he finds what is happened in the bond market right now “in any way, shape, or form concerning for financial stability”, Greenspan replied that “it’s obvious that you ought to be looking at the price earnings ratio in bonds to income. We get very nervous when the stock price index goes to high PE. We ought to be somewhat nervous when the bond rate does the same…. To believe that we can keep rates down here for very much longer strikes me as to say that human nature is going to change, and that’s one thing I wouldn’t bet on.”

He did not mention that the only reason why there continues to be such an unprecedented stampede into fixed income, pushing yields to record (negative) lows, is because investors are merely frontrunning central banks; they also know that as monetization accelerates and as private supply leave the market, the same central banks will purchase whatever bonds they can find at any price, and that is the only reason why global bond yields are where they are.

Instead he said the following:

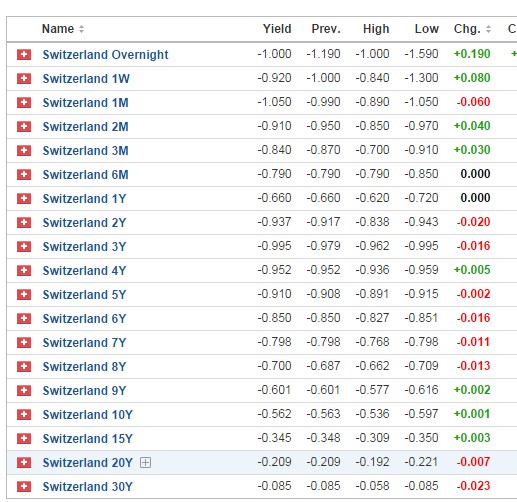

The best way to view negative interest rates is to think in terms of the fact of, where, for example, securities denominated in the Swiss franc, the yields on those, versus, for example, the Italian lire as it used to be, the Italian euro now. But that spread hasn’t changed very much for a very long period of time. So when global deflation takes hold, as it has, all interest rates fall, but the spread doesn’t. So, in order to maintain that spread, Swiss interest rates have got to turn negative. Now, the question is, how far can they? Well, there is an arbitrage, that obviously one can get.

For example, in the United States, if interest rates got very negative, what we would do is all get in to currency in which it’s a zero interest rate — I should say it’s a zero cost. We would get into currency, stack it all up in, I would say, in a vault somewhere. The problem with that arbitrage, obviously, is there’s a limited amount of currency you can hold, so at some point, something is going to give. The initial sign is going to be a big pickup in the holding, for example, of U.S. currency, both here and abroad – sorry, parenthetically, very large part of currency, U.S. currency, is held outside the United States.

| Which reveals an interesting tangent: to Greenspan, a key indicator of when the system begins to tip over is when the run on the US physical currency begins, not so much in the US as abroad. And speaking of tipping over, Greenspan was quite clear: “it hasn’t happened, but it will.”

Swiss Yields are negative until 30 years bonds

|

|

Remaining on the topic of currency, Greenspan then tied in the issue of surging currency vol, to his favorite topic: unsustainable entitlement costs. Answering a question what is causing global foreign exchange volatility, Greenspan’s responded as follows:

I think the cause of it is that there’s a very significant amount of uncertainty in the global economy. It’s coming from the fact that, as I indicated before, in the United States, we’ve got very, very major entitlements problem, which politically, I don’t see how we’re going to touch. We went through two conventions. The word entitlements never got raised, except, let’s do it more. Now, we’re going to have to cut back. There’s no physical way to continue doing this without destabilizing the financial system. So, it will stop, but the problem is that it’s going to take a while before the political system adjusts. So, it’s hard for me to see how we get out of this unless we address that problem first.

But more important than his discussion on bonds or currencies, was Greenspan’s explanation of “what he is most concerned about”, namely stagflation – the same economic problem that we wrote about in early April in a post titled: “The Next Big Problem: “Stagflation Is Starting To Show Across The Economy.” The former Fed chairman agrees, as follows:

Three fourths of the major economies, OEC economies for example, have, over the last five years, have had a less than a one percent annual rate of upward growth. The economy can’t go anywhere under those conditions, and we’re getting a state of stagnation which is not only evident in the United States but pretty much throughout Europe and the far east. And as a consequence of that, it’s very difficult to see where the next step is except what I’m concerned about mostly, is stag–flation, meaning I think we’re seeing the very early signs of inflation beginning finally to pick up as the issue of deflation fades.

Greenspan is then asked about these two elements, “the stag and the flation. How acute is this problem with productivity, the lack of growth? Do you see a recession in our future within the next 12, 18, 24 months?”

It’s very difficult to say. In fact, I don’t think you can describe the world economies in terms of the old conventional issue of inflation, recession, and the like. What we are dealing with is a population that is aging very rapidly, and that is inducing a major increase in so-called social benefits, what we in the United States call entitlements. And that is dominating the whole financial system, and until we come to understand that we have got to slow this rate of growth, which in the United States has been 9% per year since 1965, we are now down to the point where it’s taken so much savings out of the economy that we’re not getting enough investment, but that has very little to do with whether we’re going in a recession or not. I think we’re just in a stagnation state.

That covers the “stag.” How about the “flation“?

Well we’re beginning to get a pickup in wages beyond the rate of growth of productivity, and that is usually the best indicator. But, just as importantly now, is that since money, at the end of the day, is what causes inflation, we have been seeing, since the beginning of the year a significant pickup in the rate of money supply growth, and over the very long-run, it’s the ratio of money supply divided by the real GDP capacity to produce, which ultimately determines the price level. It’s a very rough indicator. It doesn’t work for two or three years and then it pops in. But over the long-run, it’s never failed. And we’re in a situation now where looking at the interest rate levels that we’re looking at and the inflation rates we’re looking at, it’s very clear that we’re going to be moving reasonably shortly into a wholly different phase.

In retrospect, between the soaring welfare costs, and the upcoming stagflationary hit, it is also very clear why exactly a month ago Alan Greenspan also warned that not only is a crisis imminent but that it is paramount to “return to the gold standard” immediately. We doubt that will happen.

Much more in the full interview below: