The election result means the risk of an anti-system coalition has risen, but remains relatively low.Italian voters have shifted significantly to the right and towards populist parties in Sunday’s election, with a huge split between the North and the South. More than 50% of the votes went to Eurosceptic parties (Five Star Movement and the Northern League). As no single party or coalition won an absolute majority, negotiations to form a new government will start after parliament reconvenes on 23 March and could extend until the summer.The election result means the risk of an anti-system coalition (La Liga + Movimento 5 Stelle) has increased, but remains low, in our view. The centre-left Democratic Party might decide to participate in a M5S-led government to block an anti-establishment

Topics:

Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Italian coalition, Italian economic challenges, Italian elections, Italian political uncertainty, Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

The election result means the risk of an anti-system coalition has risen, but remains relatively low.

Italian voters have shifted significantly to the right and towards populist parties in Sunday’s election, with a huge split between the North and the South. More than 50% of the votes went to Eurosceptic parties (Five Star Movement and the Northern League). As no single party or coalition won an absolute majority, negotiations to form a new government will start after parliament reconvenes on 23 March and could extend until the summer.

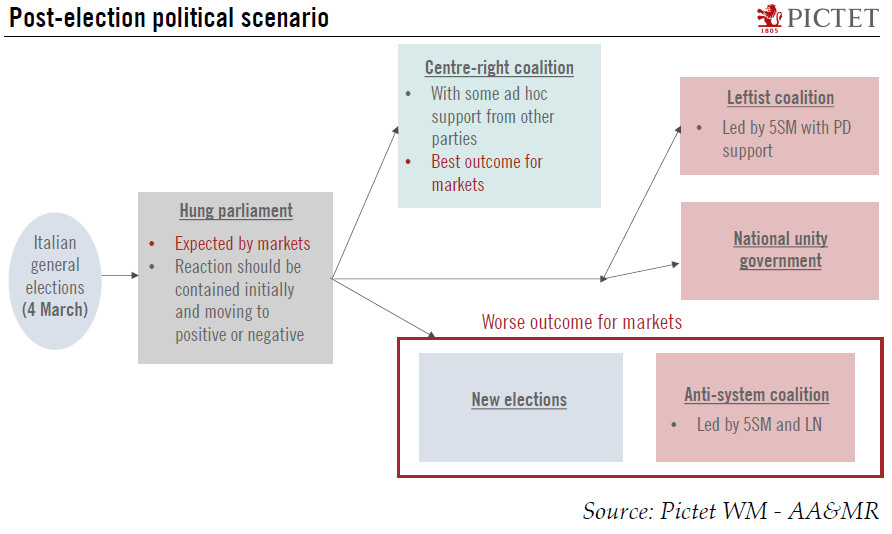

The election result means the risk of an anti-system coalition (La Liga + Movimento 5 Stelle) has increased, but remains low, in our view. The centre-left Democratic Party might decide to participate in a M5S-led government to block an anti-establishment coalition from achieving power, although we think it is more likely we will end up with a fragile centre-right coalition, centered around Forza Italia and La Liga with some ad hoc support from other parties. That being said, if none of these options materialized, the President may have to accept that there is no working political majority. One solution would be to ask all political parties to agree on a national unity government, for a limited time. New elections cannot be ruled out as well.

Whatever Italy’s next government looks like, the chances that it will push through long-term structural reforms to improve economic performance or to tackle the country’s huge public debt appear low. Based on election promises, the situation could even worsen. Already, Italy is not in compliance with EU fiscal rules. While there is no government in place, the European Commission is likely to wait before opening procedures against Italy until the situation stabilises. Nevertheless, rising tension with the EU and fiscal slippage could further heighten market concerns about Italy’s debt sustainability.

Significantly, Italian parties have dropped proposals to hold a referendum on the euro, but whoever manages to form a government is unlikely to show any eagerness to tackle the root problems that Italy faces. Thus, while near-term risks seem contained, investors are likely to become less sanguine about the medium-term outlook as monetary and external tailwinds are likely to wane gradually.