In what has become a four-part series, we are looking at the monetary science of China’s potential strategy to nuke the Treasury bond market. In Part I, we gave a list of reasons why selling dollars would hurt China. In Part II we showed that interest rates, being that the dollar is irredeemable, are not subject to bond vigilantes. In Part III, we took on the Quantity Theory of Money head-on, and showed the counterintuitive property that, the more dollars are out there, the greater the demand. Now in this essay, we will tie this all together. You could say it in one sentence: the regime of irredeemable currency has unintended consequences. We often say that we do not prefer the term “unintended consequences” because

Topics:

Keith Weiner considers the following as important: 6) Gold and Austrian Economics, 6a) Gold & Bitcoin, Basic Reports, bond market, China, Featured, irredeemable, newsletter, replacement of dollar, Reserve Currency, Treasury

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

In what has become a four-part series, we are looking at the monetary science of China’s potential strategy to nuke the Treasury bond market. In Part I, we gave a list of reasons why selling dollars would hurt China. In Part II we showed that interest rates, being that the dollar is irredeemable, are not subject to bond vigilantes. In Part III, we took on the Quantity Theory of Money head-on, and showed the counterintuitive property that, the more dollars are out there, the greater the demand.

Now in this essay, we will tie this all together.

You could say it in one sentence: the regime of irredeemable currency has unintended consequences. We often say that we do not prefer the term “unintended consequences” because it puts the emphasis on the alleged intentions of those who perpetrated it. As we discussed in another recent article, John Maynard Keynes’ intentions really were evil.

We prefer to discuss perverse incentives, which of course drive economic actors to perverse actions, which inevitably lead to perverse outcomes. Some economists can predict the perverse outcome of each policy. Later, when the tragic results play out, the rest of humanity cries “we could not have known.”

Every aspect of the regime of irredeemable currency is perverse. Of course it is perverse, it was designed for a perverted purpose: to enable the government and its cronies to borrow more, at cheaper rates, so they can spend more. Forget about inflation, employment, GDP, etc. These are just sales tools. The Fed exists to let the government buy more votes with more spending, borrowing without the means or intent to repay.To get away with it, government must do two things. One, misdirect attention so that people do not understand they are lending. They define the dollar as money, so holders do not realize they are lending. After a few generations, even free-marketers will defend this ersatz money. Two, it is imperative to take away the savers’ means of opting out.

This also harms the borrowers. They are subject to the interest rate, which alters their burden of debt. When the rate is falling, as from 1981 through present, the burden of every dollar of debt is rising. Debtors increase their demand for dollars.

An irredeemable currency is a trap. Like the old Roach Motel commercial, people (alas, not cockroaches) can get in but they cannot get out. It might seem like any dollar holder or dollar debtor can get out any time they want (ask a heroin junkie if he can stop any time he wants). If you don’t want to hold the dollar, you can choose another asset or currency—but that incurs price risk in addition to default risk.

Chinese businesses hold vast quantities of dollars as assets on their balance sheets, as does the People’s Bank of China. And they also owe vaster quantities of dollars.

As an aside, let’s put this in perspective. There is a total of $73 trillion of dollar-denominated debt out there (data source: St. Louis Fed ASTDSL + ASTLL data series). By comparison, M2 measure of money supply is just $14.7 trillion. The Fed discontinued M3 in 2006, but publishes the OECD data, currently at $14.5 trillion.

This data makes sense, if you think about it. Who would carry a cash balance bigger (or the same size) as their total short term plus long term debt? They don’t need the cash, sitting in the basement, to pay off the loan balance. They need the cash flow to make the monthly debt service payment.

The debtors are trapped in the dollar regime too, though for different reasons than the savers. They must constantly generate dollar revenues to pay the vigorish, or else lose their assets and businesses to foreclosure by their lenders.

And this brings us squarely to China. Like everyone else, they are trapped. As a major holder of dollars, the PBoC is trapped like any saver. If they sell their dollars, what other currency would they buy? How much would they lose in the process of dumping such a vast quantity, and buying up a like quantity of something else?

As a major group of dollar debtors, Chinese businesses are trapped like other debtors. They must keep generating dollar revenues. Could the Chinese government pass a law to let them off the hook? Let’s consider that.

Some of them owe the dollars to Chinese banks. Since lender and borrower are both subject to Chinese law, the government could in theory direct them to redenominate it in yuan at some exchange rate. Presto, yuan debt. Leaving aside that many of these companies manufacture products which have no domestic Chinese demand, the problem with this is that the lender—the Chinese bank—has, itself, borrowed those dollars that it lent. So China would have to back this law with another policy. It would have to decree that China will not honor its dollar obligations henceforth.

This policy would bring instant disaster. Obviously, the rest of the world would stop extending any credit to China. China would become a pariah. Also, China has those vast holdings of Treasury bonds. We might expect the US government to seize China’s Treasury bond holdings, to indemnify the banks who lent to China. The US government could also find and seize many other Chinese owned assets within US jurisdiction.

In an interconnected world, one does not casually default on one’s debts. It would be surefire self-destruction. Even in 1981, even the United States government feared what it might trigger by its gold default (and a near-miss with a monetary crisis ensued over the next decade).

Let’s return to the idea of China selling off is bonds. Perhaps they would think to do this first, before announcing any intention to default. As discussed, one problem is taking losses to dump such a large position. But suppose they accept that. Another is that there are no other markets big enough to absorb the flows. The losses they would take getting into another currency would dwarf those they took getting out of the US dollar.

The next-biggest currency is the euro and right now, to put it mildly, there is chaos on the ground in the Old World. Italy now has a leader who threatens (we don’t know how serious this is) to abandon the euro and reissue the lira. China would be buying into this??

Another problem can be understood with some simple examples. If you, an individual, have $100 then you can put Federal Reserve Notes in your pocket. You are a creditor to the Fed, who lends to the government and the banks.

If you, a wealthier individual, have $100,000 then you can put it in a bank. It’s not reasonable to carry around that many paper bank notes. You are a creditor to the bank, who lends to the government, corporations, businesses, and individuals.

If you, a corporation, have $100,000,000 then you can put it in the commercial paper market. You can get a bit more interest, by lending directly to major corporations.

If you, a sovereign government, have $100,000,000,000, then there is only one place to put it. Treasury bonds. Not only is there no other currency that can absorb this much, but within the dollar there is no other instrument that can. You are a lender to the US government.

However, there is one other fact that must be observed. If you sell, you are not selling bonds against the dollar. That means you are not making the bond price go down in dollar terms. Which means you are not making the interest rate go up. If China sells, it’s not looking to hold Federal Reserve Notes in preference to Treasury bonds. It would be seeking, we presume, to get out of the dollar altogether. And this means selling the Treasury bond for a euro bond or a British bond or, well, something.

To reiterate, China wouldn’t be selling bonds against the dollar. It would be selling the dollar against another currency. This would not make the US interest rate go up, but the dollar go down against another currency.

Assuming there is another currency that could absorb the flows (which there isn’t), assuming that there is another currency that is less bad than the dollar (nope), and assuming the losses would be acceptable (we doubt it), there is one final problem. The other currencies are dollar derivatives.

Just as the PBoC issues yuan to buy a portfolio of Treasury bonds, so do the other central banks. The worldwide regime of irredeemable currency is a dollar regime. It is derived from the dollar, and cannot be separated from the dollar.

It would be funny enough to be a cosmic joke, if it weren’t deadly serious. When the Allies knew they would win World War, they sat down at Bretton Woods to decide how the world’s monetary system would work after the war. The US found itself to be in a unique position. It could dictate terms, and the rest of the world had little choice. Keynes, a Brit, was famously not happy with how it worked out, but even staunch ally Britain was in no position to argue with the US.

The world conceded to use the US dollar as if it were gold. The dollar would remain redeemable to governments for a while (though not Americans since 1933). However, once they began redeeming in growing quantity, President Nixon defaulted and ended redeemability entirely in 1971. From then on, the Treasury bond passed as the surrogate gold. It is believed to be the risk-free asset. Let’s just say that if you believe it is free of all risks, then we have a bridge to sell you in Brooklyn.

The man representing the US was a Roosevelt administration man named Harry Dexter White. White was later discovered to be an agent of the Soviet Union. We can assume that he was not concerned with the long-term well-being of the US in the plan he forced onto the world at Bretton Woods. And his plan was certainly not to the benefit of anyone, least of all the US.

China (or any other government) cannot extricate itself from the dollar. And even if it could, it would not affect the interest rate but the price of whatever currency China would buy. This would not alter the fact that the other paper currencies are farther along the trajectory into the black hole of zero.

No paper currency can replace the dollar. One thing can, but it is not paper. It is a heavy metal, yellow in color. By complete coincidence, Keith had a chance to hold a 12.5kg bar made of it. Here is a picture taken on the scene. We could tell you where it happened, but then we would have to kill you…

| Gold will replace the dollar. It will not be by any revelation of truth about the dollar. Nor is it a matter of the price of gold (which is inverse to the price of the dollar, in gold—currently 23 milligrams). Gold was no closer to replacing the dollar when it was $2,000 and would be no closer at $20,000.

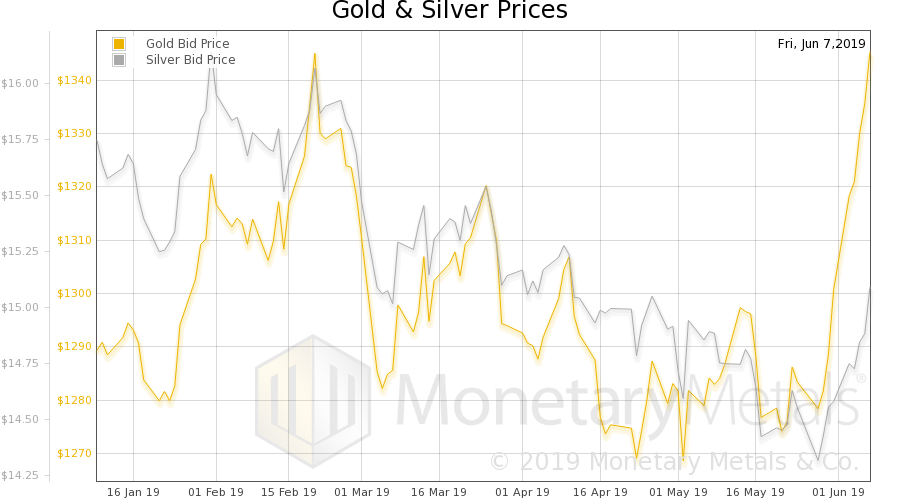

It will take bonds, that is, credit. There must be a mechanism to refinance dollar debts in gold. Unlike dollar debts, gold debts can be extinguished by paying metal. We are developing that mechanism. Monetary Metals is excited to be bringing the first gold bond to market. Please contact us if you are interested in investing. Supply and Demand FundamentalsThe price of gold jumped 35 bucks this week, and that of silver 48 cents. The dollar is now down to 23 milligrams gold. Keith is on the road this week, so we will just comment on one thing. If Italy is serious about moving back to the lira, that will make the euro less sound (to say nothing of the lira). That will drive people mostly to the dollar, but also to gold. |

|

Gold and Silver PriceLet’s go straight to the supply and demand picture of gold. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver. |

Gold and Silver Price(see more posts on gold price, silver price, ) |

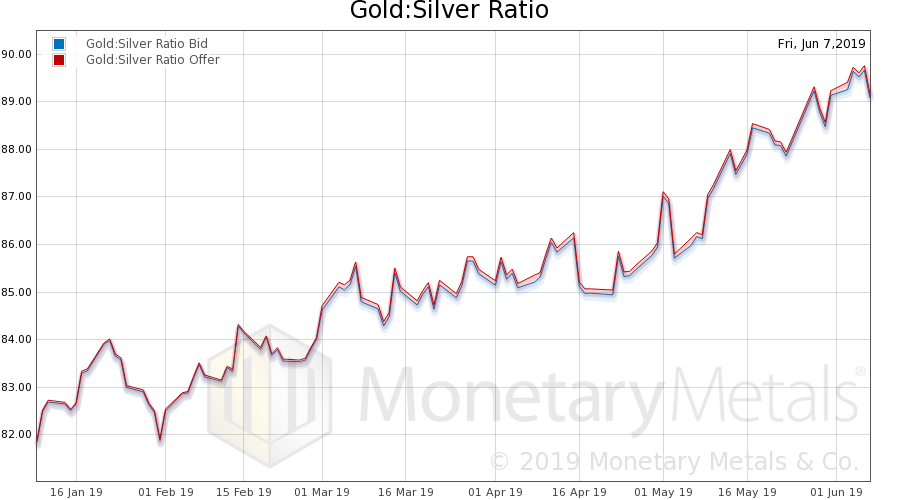

Gold: Silver RatioNext, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio rose dropped slightly. |

Gold: Silver Ratio(see more posts on gold silver ratio, ) |

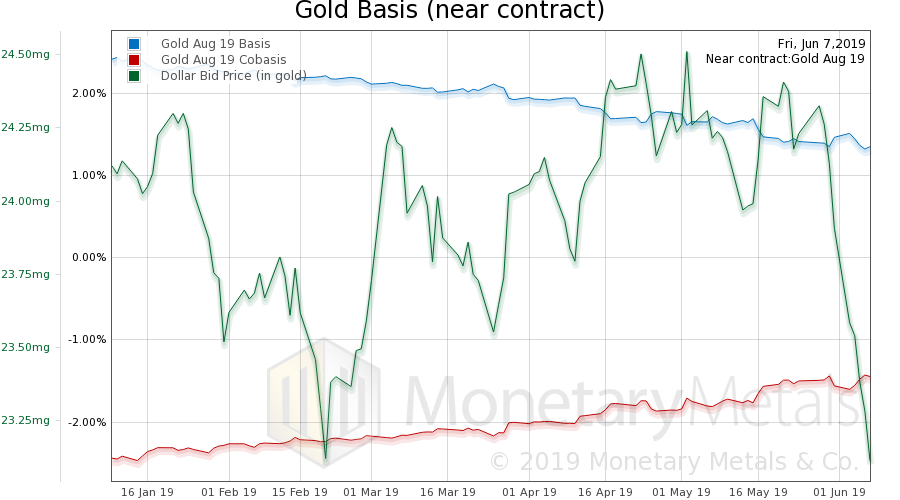

Gold Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar PriceHere is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price. Another big drop in the dollar, and not so much change apparent in the scarcity (i.e. cobasis). The gold basis continuous did show a small move. The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price jumped $42 to $1,414. |

Gold Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar Price(see more posts on dollar price, gold basis, Gold co-basis, ) |

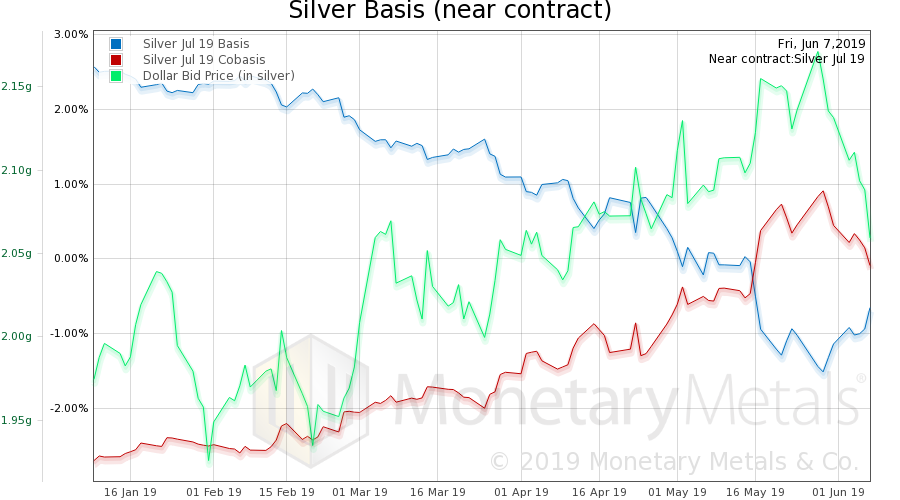

Silver Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar PriceNow let’s look at silver. In silver, the picture is a bit different. The July contract had been backwardation, but no more. The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price was up 19 cents, to $15.65. |

Silver Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar Price(see more posts on dollar price, silver basis, Silver co-basis, ) |

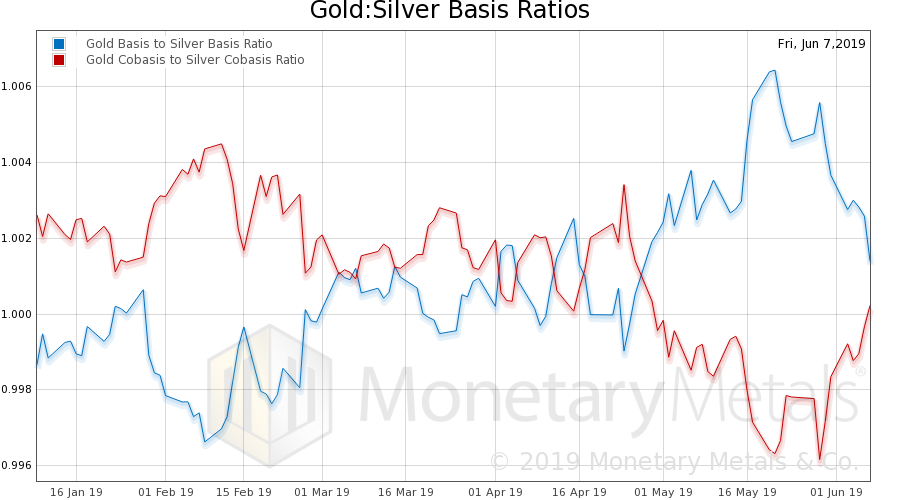

Gold: Silver Basis RatiosHere is an update of the ratios of the gold to silver basis and cobasis. So much for that trend. |

Gold: Silver Basis Ratios |

© 2019 Monetary Metals

Tags: Basic Reports,bond market,China,Featured,irredeemable,newsletter,replacement of dollar,reserve currency,Treasury