Eurostat confirmed earlier today that Europe has so far avoided recession. At least, it hasn’t experienced what Economists call a cyclical peak. During the third quarter of 2019, Real GDP expanded by a thoroughly unimpressive +0.235% (Q/Q). This was a slight acceleration from a revised +0.185% the quarter before. The real question, though, is whether the business cycle approach means anything in this day and age. I don’t think it does, and that’s a big part of why there’s so much confusion about both cause and effect. For most people, certainly every monetary policymaker and central banker around Frankfurt, the more important number is 26. As in, Real GDP across all of the nineteen countries of the Euro Area has been positive for twenty-six straight quarters.

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, currencies, Dollar, downturn, economy, Euro, EuroDollar, Europe, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, Germany, globally synchronized downturn, globally synchronized growth, industrial production, Italy, Markets, newsletter, real GDP, Recession

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

|

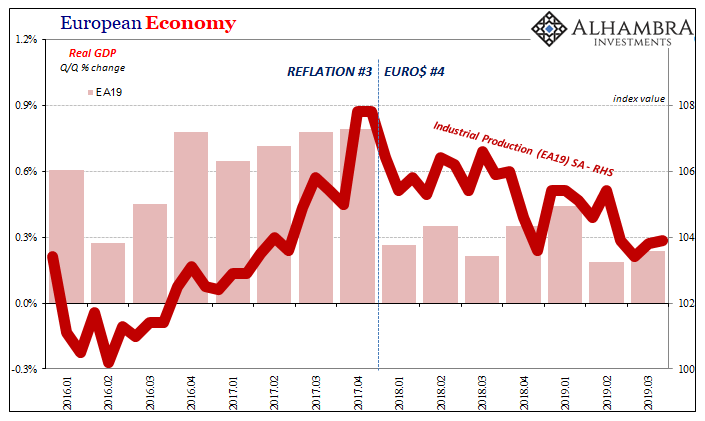

Eurostat confirmed earlier today that Europe has so far avoided recession. At least, it hasn’t experienced what Economists call a cyclical peak. During the third quarter of 2019, Real GDP expanded by a thoroughly unimpressive +0.235% (Q/Q). This was a slight acceleration from a revised +0.185% the quarter before. The real question, though, is whether the business cycle approach means anything in this day and age. I don’t think it does, and that’s a big part of why there’s so much confusion about both cause and effect. For most people, certainly every monetary policymaker and central banker around Frankfurt, the more important number is 26. As in, Real GDP across all of the nineteen countries of the Euro Area has been positive for twenty-six straight quarters. It’s a seemingly impressive run of now six and a half years. Mario Draghi has taken full credit for this, beginning long before he retired recently. But upon closer examination you can see how something is just not right. Recession is the wrong bogeyman to focus on. There are, actually, much bigger problems and concerns hidden within these figures which remain on the plus side of zero. These are obscured because of the way in which we measure “expansion”, in linear terms. First, though, the cause. US President Trump beginning to talk seriously about imposing tariffs on Chinese goods in the middle of 2018 cannot ever explain why the economy for nearly all of Europe clearly ran into a wall at the end of 2017. Economists, including those in Europe and at Europe’s central bank, have tried very hard to blame if not directly those trade tariffs then trade war and general protectionist sentiment. |

European Economy, 2016-2019 |

| According to their view, because we all know it cannot possibly be a global monetary problem, not with so much global QE’s and “money printing”, German and Italian industrial firms must have been worried about an issue that hadn’t yet been raised and so began cutting scaling back for a far distant future event that didn’t actually concern them. Yeah, it doesn’t come close to adding up.

No, what changed right at the outset of 2018 was the euro – meaning the dollar. The early warning signs of late 2017 were swallowed up by the inflation hysteria sweeping the globe, especially in Europe, where it was said recovery had been found at long last. Mario Draghi most of all. While he was saying it, though, the economy fell out right from beneath his feet. It didn’t lead to the mainstream view of recession, several negative quarters of GDP, but it has added up to something like that already. With these new figures in hand, that’s seven quarters and counting of…something. |

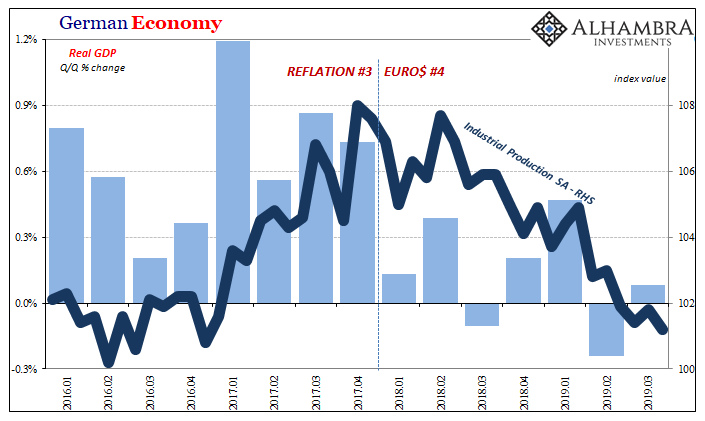

German Economy, 2016-2019 |

| Here’s what I mean:

Not only did the underlying financial circumstances change, they did so in economic circumstances going right through the industrial sector. That much is obvious and consistent especially in Europe’s biggest economic constituents: |

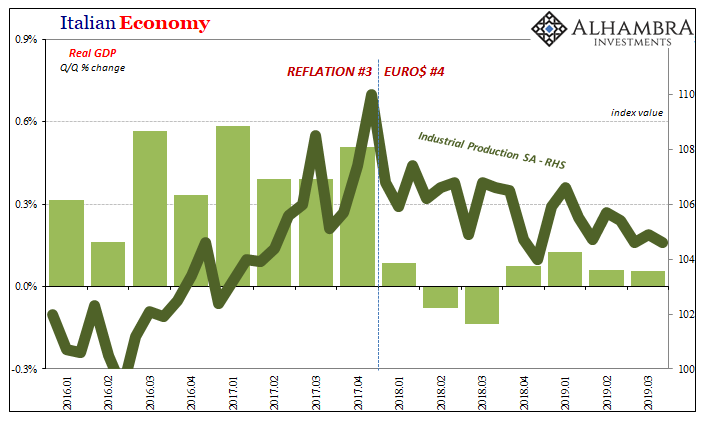

Italian Economy, 2016-2019 |

| Up until the end of 2017 there was modest (it wasn’t really robust, but that’s an argument for another day) growth, and then there wasn’t. If not European recession, then some kind of extended downturn.

The key word is not downturn just like it wouldn’t be recession. The more important one is the first: extended. What’s more, this is actually quite typical meaning we’ve seen this all before. Same pattern with only slight variations. The last time Europe was declared in recession, it looks very familiar. The economy seems to slam into a wall of unknown origin (unless you were paying attention to what was going on in offshore US$ liquidity during the second quarter of 2011). |

European Economy, 2009-2013 |

| In this earlier case, the same thing as we can observe nowadays; there was modest growth, not really a recovery, followed by what was then a downturn consistent with the accepted definition for recession. The difference, therefore, is the merely the size or depth of the downside.

And I would argue that that isn’t much difference really at all. Though GDP has remained positive over these last seven quarters, this only masks the degree of what really is further contraction. Again, non-linearity. At this point, near-zero but still positive GDP in all of 2018 and 2019 so far is the same as the eight quarters of the mostly negatives you see during 2011 and 2012. |

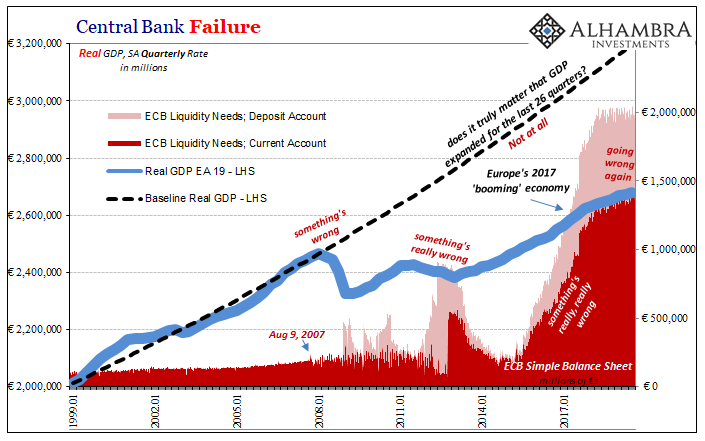

Central Bank Failure, 1999-2017 |

The reason is more obvious on the chart below:

Recession focuses us in on specific definitions of the downside in terms of its amplitude, thereby downplaying the fact that it is the frequency that under these conditions really matters.

In other words, flip it around; both the 2011-13 recession as well as the last seven quarters of not-recession have resulted in effectively the same thing – several years of no upside. That’s the real problem, the real danger especially as what it means is falling further and further behind.

That economy is so much more behind in 2019 than it was by the end of 2012 that small positives now are, again, pretty much the same thing as moderate negatives back then.

Europe cannot afford this downturn, even if it never becomes a fully acknowledged recession (which it still might, maybe even likely will!) Seven quarters (SEVEN!) and counting where marginal growth just disappeared for reasons that no one can explain. It sure wasn’t trade wars, and certainly not trade war sentiment.

Thus, this new post-crisis business cycle does not alternate between expansion and recession as it had in the past, rather it oscillates back and forth between some growth and then its curious disappearance. The downturn side may be variable, but its effects equally harmful no matter the variation; whether or not it becomes recession in Q4 2019 or at some point in 2020.

What actually matters is that “dollar”-infused inflection; hitting the wall of a sudden global dollar shortage. As soon as that happens, it changes the cycle; modest growth gone, replaced by the extended lack of any.

It is recession in terms of time, the more important of its dimensions. A time recession, if you will. That’s the aspect that will ultimately make the biggest negative contribution. The eurodollar squeezes are costly most on those terms. Across Europe, seven more quarters and counting.

Tags: currencies,dollar,downturn,economy,Euro,EuroDollar,Europe,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Germany,globally synchronized downturn,globally synchronized growth,industrial production,Italy,Markets,newsletter,real GDP,recession