If the mainstream is confused about exactly what rate hikes mean, then they are not alone. We know very well what they are supposed to, but the theoretical standards and assumptions of orthodox understanding haven’t worked out too well and for a very long time now. The benchmark 10-year US Treasury is today yielding less than it did when the FOMC announced their second rate hike in December. Thus, despite two rate hikes in between, the 10-year is largely nowhere. This is not the only place where we can observe such lack of direct action. More importantly, eurodollar futures have accomplished much the same price history. That is far more of a problem for the orthodox framing because eurodollar futures are supposed to be a direct reflection of those rate hikes, or at least the effects of them on money rates in the future. Though there may not be a one-to-one relationship, should there not at least be some relationship? The bond market is already skirting the contours of another Greenspan-ism, a possibility that my colleague Joe Calhoun and I talked about back in December though it might have looked like “interest rates had nowhere to go but up.” I believe his words were, “watch, we could very well revisit the conundrum here.” The “conundrum” refers to, of course, how the bond market mystifies economists.

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke, bonds, bubble, conundrum, currencies, depression, economy, eurodollar futures, eurodollar futures curve, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, Interest rates, Markets, Monetary Policy, newsletter, QE, The United States, U.S. Treasuries, Yield Curve, ZIRP

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

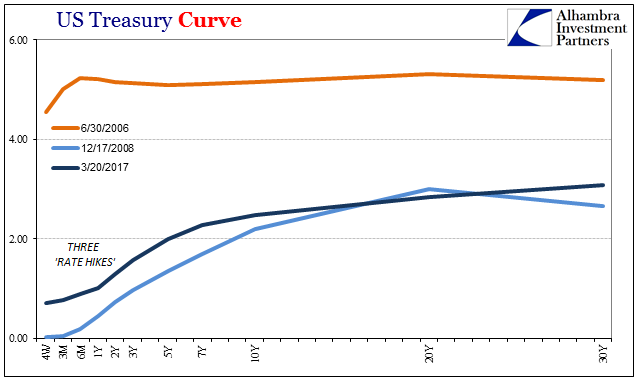

If the mainstream is confused about exactly what rate hikes mean, then they are not alone. We know very well what they are supposed to, but the theoretical standards and assumptions of orthodox understanding haven’t worked out too well and for a very long time now. The benchmark 10-year US Treasury is today yielding less than it did when the FOMC announced their second rate hike in December. Thus, despite two rate hikes in between, the 10-year is largely nowhere.

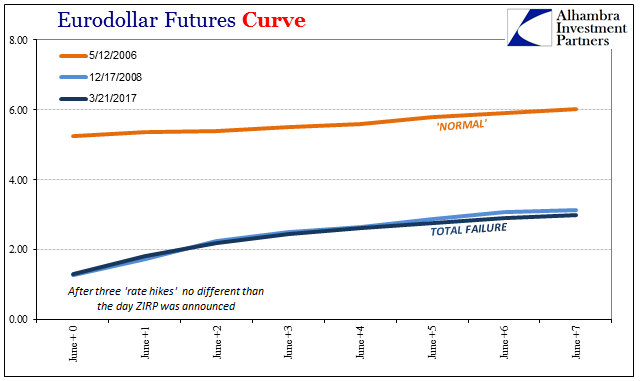

This is not the only place where we can observe such lack of direct action. More importantly, eurodollar futures have accomplished much the same price history. That is far more of a problem for the orthodox framing because eurodollar futures are supposed to be a direct reflection of those rate hikes, or at least the effects of them on money rates in the future. Though there may not be a one-to-one relationship, should there not at least be some relationship?

The bond market is already skirting the contours of another Greenspan-ism, a possibility that my colleague Joe Calhoun and I talked about back in December though it might have looked like “interest rates had nowhere to go but up.” I believe his words were, “watch, we could very well revisit the conundrum here.”

The “conundrum” refers to, of course, how the bond market mystifies economists. In truth, because economists are statisticians they hold very little appreciation for investments or investing, preferring instead to try to quantify and compartmentalize (according to efficient markets and rational expectations theory) every little bit so as to reduce price information to meaningless but numerical platitudes. I have already discussed at some good length the converse condition a year ago in their form of “term premiums.”

At issue is what makes an interest rate. Most of the time, it is market forces of all kinds of perceptions competing for attention and being ruthlessly evaluated. In times like this, one of those vying for consideration is monetary policy. Economists and central bankers have an established tendency to make monetary policy the primary parameter in all financial arrangements, but more so in things like the “risk free” rate or eurodollar futures where Fisherian deconstruction seems to demand those priorities.

The Federal Reserve had occasion to preview these conditions in the middle of the last decade. We know that was the height of the housing bubble, but it was also the apex of another kind of bubble, a sort of self-congratulatory echo chamber where everything that was good was put on the Fed’s side of the ledger and on the flimsiest of evidence. That included, as it turned out, several things the Fed hadn’t even done yet, the “non-standard” policies like ZIRP and QE.

The Federal Reserve Board’s Division of Research and Statistics published one such paper in 2004. The US central bank was very well aware of the Japanese central bank’s struggles with “non-standard” policy and therefore wished to provide “evidence” basically for how they would get it right where Japan did not. In other words, the Japanese were empirically disproving QE and ZIRP, but this Fed offering (and others) decided that it wasn’t QE that was generically being challenged but rather Japanese QE under question.

In brief, we have developed new empirical evidence on the likely effects of nonstandard monetary policies near the zero bound. Notably, the Federal Reserve has successfully used its communications to affect expectations of future policies and thus longer-term yields. We also find some evidence that relative supplies of securities matter for yields in the United States, a necessary condition for achieving the desired effects from targeted asset purchases. The event studies for Japan do not provide much evidence that the Bank of Japan has been successful in using nonstandard policies, but the term structure analysis does suggest that longer-term yields have been lower than might have been expected in recent years, holding open the possibility that the ZIRP and quantitative easing policies have had beneficial effects.

There were three authors for this paper reaching this US-will-do-it-right conclusion: Vincent Reinhart who was at the time the Fed’s Director of the Division of Monetary Affairs; Brian Sack, then the head of the Monetary and Financial Markets section at the Federal Reserve, who would go on to lead FRBNY’s Markets Group as well as run the System Open Market account there; and Ben Bernanke.

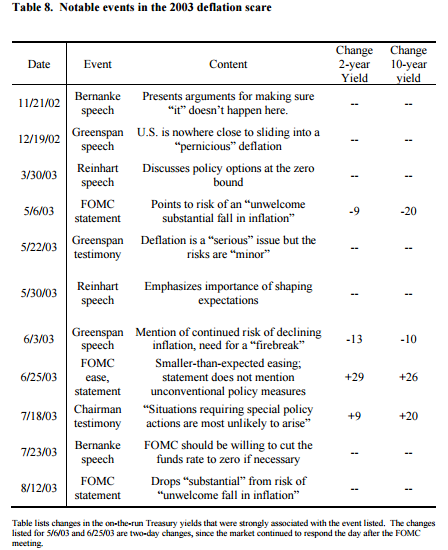

It is a long and laborious paper filled mostly with mathematics, a staple of any Bernanke offering. The concepts put forth, however, were very simple – the Fed can influence long-term interest rates through communications, and long-term interest rates are stimulus. in policy terms, the Fed talks down long term inte To provide empirical “evidence” for this position, there was a good deal of focus on the bond market’s reactions to the public debate over monetary policy during 2003. Prior to the events of August 2007 and thereafter, much discussion centered on this period and for good reason – though the dot-com recession had officially ended in 2001, the economy remained weak while stocks continued their torturous grind lower. From the official policy standpoint, there was open talk of deflation.

| And it was that talk which Bernanke, Reinhart, and Sack used to craft their pro-communication position.

Interest rates outside the short end of the UST curve seemed to respond where policymakers were expressing the possibility of using “non-standard” measures including something like QE. But was the bond market actually reacting to the prospect of the Fed buying UST’s, or was it instead judging the risks of economic and financial conditions which might force the Fed to act in that way? It will not surprise you to learn the authors favored the former chain of causation, only alluding to the latter without explaining why it wasn’t to them as convincing:

|

Notable events in the 2003 deflation scare |

| We have to further recognize that “deflation” is not a necessary condition for yields to fall. Monetary policymakers may be prone to attribute monetary policy to all things they view positively, but bond markets above all and especially UST’s exhibit a clear and historical liquidity effect where in times of great uncertainty there is no need of threat for QE by which yields would decline. Instead, it is much more reasonable that talk of QE in 2003 merely reinforced fears that had been rising ever since three years before when the NASDAQ hit 5k and went no farther; if the Fed felt “non-standard” policies might be worth talking about, surely there was a big enough problem to prefer liquid (low risk) instruments. It is this view of bond market interest rates that has been established (over and over and over again) by the nearly thirteen years so far after the paper.

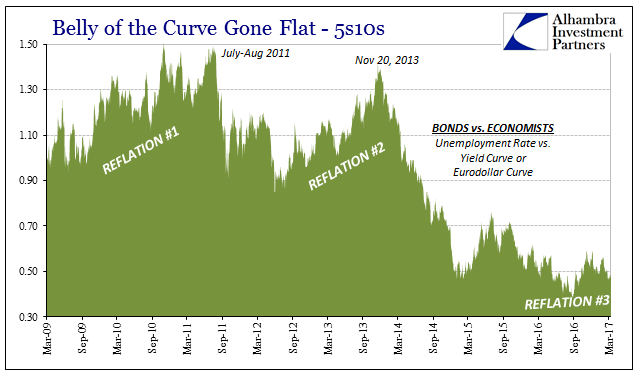

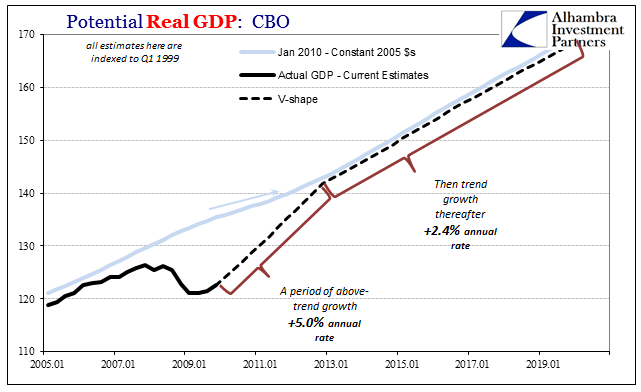

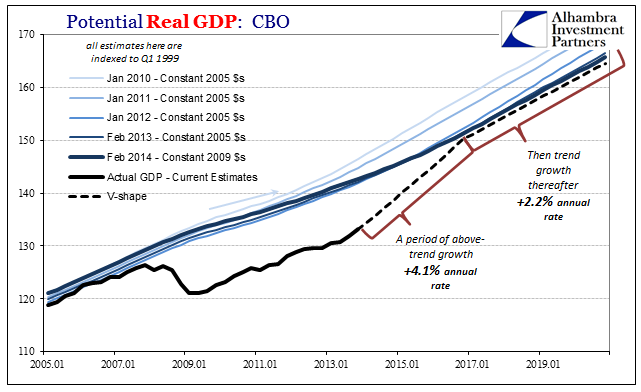

The Bernanke view, obviously, survived based on dubious mathematics rather than more applicable common sense. That’s why we got four QE’s anyway despite Japan and in 2015 more than a year after his term as Fed Chairman had expired, Bernanke was writing for Brookings trying to explain why interest rates had fallen more outside of QE than in it (and still he couldn’t do it). The consequences of getting the bond market all wrong are equally evident, but especially in the past few years where from the math the economy was supposed to liftoff but from bonds there was no reason to ever think that way outside of a brief period of “reflation” in late 2013. |

Belly of the Curve Gone Flat 2009-2017 |

| It’s especially curious that Bernanke would be so out to lunch on it, as it was Milton Friedman (Bernanke is believed a close disciple of monetarism, but he is more so of the neo-Keynesian variety and it shows) who correctly devised the framework for understanding bond market interest rates – opportunity. Liquidity preferences are simply opportunity from the opposite perspective. Falling interest rates outside of the short run are an expression of economic (which might include financial) pessimism. Thus, when LT interest rates fell after 2012 (not in a straight line) they did so because the bond market realized US QE was, in fact, no different than Japanese QE; neither had any prayer of success.

On this weighty point, both the UST market as well as the eurodollar futures market agree in total – no trivial matter since these are the two deepest and most influential markets on this Earth. The history of their curves is one where opportunity is first expressed and then bitterly walked away from. Both treasuries as well as eurodollar futures started out believing in Bernanke even after he failed so thoroughly in 2007 and 2008 (efficient markets? Not a chance). |

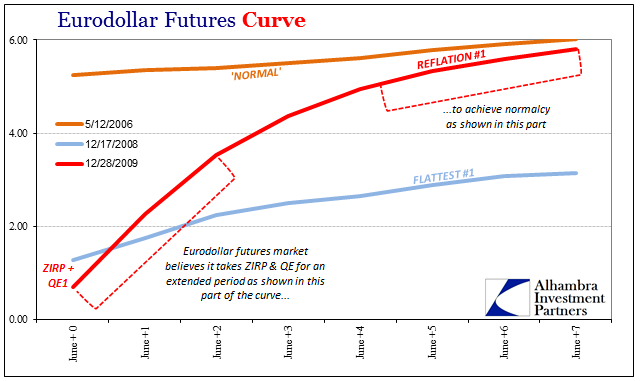

Eurodollar Futures Curve |

| The flat and shriveled eurodollar curve from December 17, 2008, is a financial take devoid of future opportunity, a more appropriate assessment given the uniform record of monetary policy failure to that point. But after ZIRP was announced, and then to where the Great “Recession” stopped its contraction, the curve echoed hope again though if somewhat more cautious in that stance (that it would take years to achieve, the lingering steepness out four and five years down the curve, while recognizing the risks it might never happen – where the outer part of the curve stopped somewhat short of “normal”).

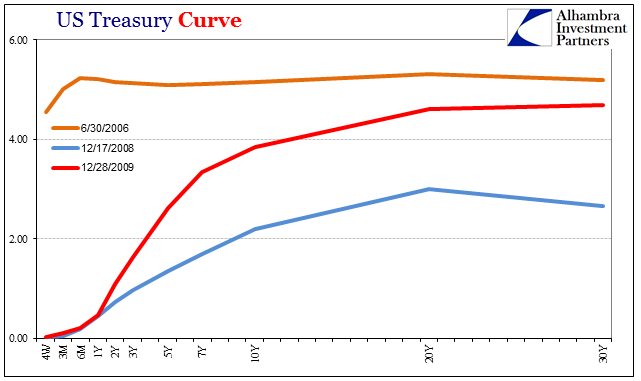

The UST curve shows us the exact same outlook in its version: |

US Treasury Curve 2006-2009 |

| The history of interest rates thereafter in nominal terms as well as these respective curves is only about opportunity to which monetary policy contributed, at times, some positive expectations. The actual transactions of QE as well as the “communication” policy of the Bernanke Fed played at most a minor (fleeting) role.

We can observe this important difference in the state of the curves today, in particular with the Fed now having “raised rates” three times and leaving the bond market as described at the outset (a renewed conundrum that is anything but). |

Eurodollar Futures Curve 2006-2017 |

| These three “hikes” have shifted only the nominal frame of reference for the curves, not their outlook on opportunity or the continued lack thereof. This “frame of reference” is an exceedingly important concept that has been bastardized and tortured by a fundamental misreading and misconception of especially the 1990’s. Bernanke in particular arrogantly claimed in the mid-2000’s central bank bubble that Greenspan’s Fed was the reason for all that was supposedly good even though Greenspan himself in private may not have been so sure in June 2003 (in no small part because of Japan’s experience). |

US Treasury Curve 2006-2017 |

| The lack of bond market reaction to the past two hikes (or the first one at all), apart from the selloff from July to November in anticipation, is about re-assessment of opportunity and not monetary policy. Things looked particularly bleak in early and mid-2016, but somewhat less so by the start of 2017. That is still not anywhere close to good, and is much more like Japan than anyone seems willing or even able to admit.

|

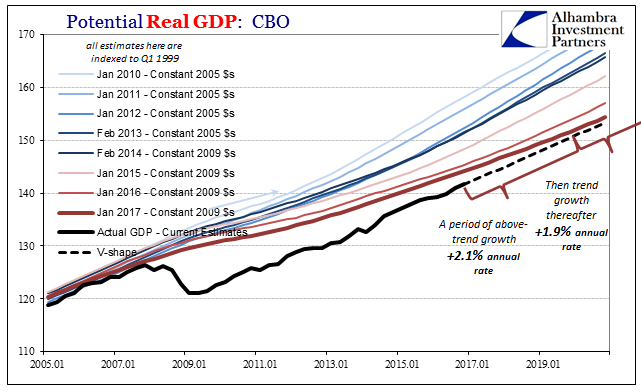

Potential Real GDP: CBO 2005-2019 |

| What does it mean that the Fed is raising rates? By virtue of Bernanke being given such a platform and still never having to account for how and why he got almost every single thing wrong (and most often backwards) the mainstream still holds views close to his. In reality, the Fed’s “hikes” mean far less than you might think. |

Potential Real GDP: CBO 2005-2019 |

Potential Real GDP: CBO 2005-2019 |

Tags: Alan Greenspan,Ben Bernanke,Bonds,bubble,conundrum,currencies,depression,economy,eurodollar futures,eurodollar futures curve,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Interest rates,Markets,Monetary Policy,newsletter,QE,U.S. Treasuries,Yield Curve,ZIRP