One of the first to use the word “euro glut” was Deutsche Bank’s George Saravelos. His idea of the euro glut is that European banks and investors drive the euro down despite the massive European current account surplus and the high European household savings rates of 12% compared to 4% in the US. Saravelos argues that ECB easing will lead to some of the “largest capital outflows in the history of financial markets”. This would counter the “European savings glut” created by savings and current account surpluses. He says: Euroglut is a global imbalances problem. It refers to the lack of European domestic demand caused by the Eurozone crisis. The clearest evidence of Euroglut is Europe’s high unemployment rate combined with a record current account surplus. Both are a reflection of the same problem: an excess of savings over investment opportunities. Euroglut is special for one and only reason: it is very, very big. At around 400bn USD each year, Europe’s current account surplus is bigger than China’s in the 2000s. If sustained, it would be the largest surplus ever generated in the history of global financial markets. This matters. Euroglut means that as the world’s biggest savers, Europeans will drive international capital flow trends for the rest of this decade. Europe will become the 21st century’s largest capital exporter.

Topics:

George Dorgan considers the following as important: capital outflows, Deutsche Bank, euroglut, George Saravelos, Monetary Policy, newsletter, savings glut

This could be interesting, too:

investrends.ch writes Bloomberg: DWS stoppt Private-Credit-Geschäft in Asien

investrends.ch writes Deutsche Bank bleibt auf Rekordkurs

investrends.ch writes DWS mit neuem Vertriebsleiter für Institutionelle

investrends.ch writes Deutsche Bank mit Gewinnsprung – Aktie steigt

One of the first to use the word “euro glut” was Deutsche Bank’s George Saravelos. His idea of the euro glut is that European banks and investors drive the euro down despite the massive European current account surplus and the high European household savings rates of 12% compared to 4% in the US.

Saravelos argues that ECB easing will lead to some of the “largest capital outflows in the history of financial markets”. This would counter the “European savings glut” created by savings and current account surpluses. He says:

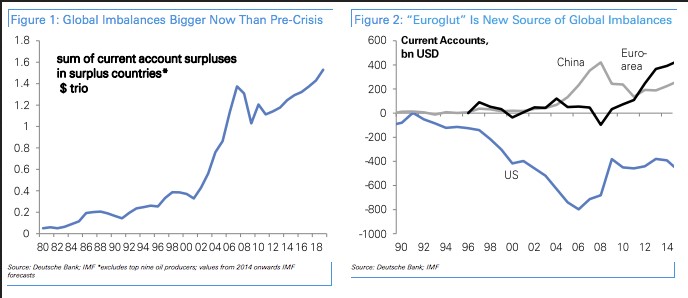

Euroglut is a global imbalances problem. It refers to the lack of European domestic demand caused by the Eurozone crisis. The clearest evidence of Euroglut is Europe’s high unemployment rate combined with a record current account surplus. Both are a reflection of the same problem: an excess of savings over investment opportunities. Euroglut is special for one and only reason: it is very, very big. At around 400bn USD each year, Europe’s current account surplus is bigger than China’s in the 2000s. If sustained, it would be the largest surplus ever generated in the history of global financial markets. This matters.

Euroglut means that as the world’s biggest savers, Europeans will drive international capital flow trends for the rest of this decade. Europe will become the 21st century’s largest capital exporter. This statement is close to an accounting identity – a surplus on the current account implies capital outflows elsewhere.

Our premise is that the next few years will mark the beginning of very large European purchases of foreign assets. The ECB plays a fundamental role here: by pushing down real yields and creating a domestic “asset shortage”, it is incentivizing European reach for yield abroad.

The outflows will help drive the euro ever lower, eventually dropping below parity with the U.S. dollar. He forecasts the euro to fetch just 95 cents by the end of 2017. Yield curves will be very flat, with U.S. fixed income a “primary beneficiary” of European demand. In fact, if there is enough demand for long-dated instruments, the 10-year U.S. yield could easily trade below terminal Fed funds, a phenomenon that occurred in the 2000s amid the so-called bond conundrum and might become more likely now thanks to ever larger current-account surpluses, he says. In the long run, this should also be good news for emerging markets as the flows make it more likely that marginal demand for emerging market assets goes up rather than down, he says. (via Marketwatch)Here an interpretation of FT Alphaville:

Think about policy over the next few years: at least 500bn-1 trillion of excess cash will be sitting in European bank accounts “earning” a negative rate of 20bps. In the meantime, asset-purchases will drive yields down across the board – there will be nothing with yield left to buy.

So, the basic argument here is that while China’s surplus drove Asian policy in the 2000s, the Euroglut will now become the key determining factor driving European policy from now on.

Here are some of Saravelos’ slides:

Saravelos predicts most of the European continent could end up with negative rates or FX managed-regimes.

Europe is the new China, and via large demand for foreign assets, it will play a dominant role in driving global asset price trends for the remainder of this decade

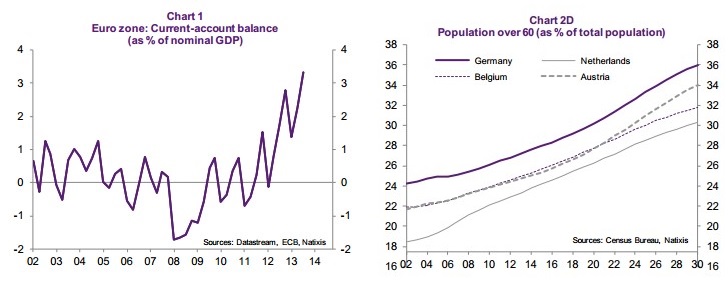

Natixis tracks the increase of the European current account. They also give one reason for the euro glut: The ageing population

For Daniel Eckert and Holger Zschäpitz of the German Welt, the euro glut was the principal reason that the Swiss National Bank gave up the peg to the euro.

We think that the ECB is happy with the euro glut. They are even happy to a certain extend when the Greek crisis further weakens the common currency. A weak euro implies more exports and more jobs in Germany and some export-oriented countries in Southern European, like Italy.

The United States are more increasing the public deficit more than most European states, hence bonds are honored with higher interest rates, 2.5% for ten year treasuries compared to 0.9% for German Bunds or 2.1% yield for Italian and Spanish government bonds (see bond rates). In times of low risk aversion, this hunt for yield translates into an outflow from Europe.

But on the other side, the weak euro may increase inflation, in particular in Germany, where strikes are frequent and labor agreements point to German wage inflation of higher than 3%. Once this wage inflation translates into consumer price inflation, then the ECB must stop her FX-centric policy.

Secondly, a capital outflow needs investible assets:But when the Fed continues to be reluctant to hike rates and when American wage inflation translates into weaker US company profits, then neither European money market funds nor stock market investors will find the required assets in the United States….. and the euro glut will stop.