Among its various options, we believe that the ECB would have to cut the deposit rate by at least 20bp to surprise the market. We have laid out our baseline scenario for this week’s ECB policy meeting, including a 10bp deposit rate cut, a 6-month QE extension and a possible broadening of the scope of asset purchases. Recent ECB rhetoric suggests that risks are tilted towards a more aggressive policy package. It would not be the first time that Mario Draghi over-delivers, although this time could prove more challenging given the (very) high market expectations, the resistance from the hawks, and the need to save some ammunition for later. In this note we review the ECB’s options if it were to surprise. In our view, the ECB’s dovish stance reflects a fundamental shift, with major implications for the economy and markets. In particular, the Governing Council’s growing focus on core inflation means their dovish bias is likely to remain in place into 2016 despite headline inflation bouncing back on energy-related base effects. Therefore, if the ECB does not deliver on all fronts on Thursday, it will likely signal that it retains ammunition for later. In other words, any market disappointment might only prove short-lived. Meanwhile, technicalities also matter.

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: Macroview, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

Claudio Grass writes The Case Against Fordism

Claudio Grass writes “Does The West Have Any Hope? What Can We All Do?”

Claudio Grass writes Predictions vs. Convictions

Claudio Grass writes Swissgrams: the natural progression of the Krugerrand in the digital age

Among its various options, we believe that the ECB would have to cut the deposit rate by at least 20bp to surprise the market.

We have laid out our baseline scenario for this week’s ECB policy meeting, including a 10bp deposit rate cut, a 6-month QE extension and a possible broadening of the scope of asset purchases. Recent ECB rhetoric suggests that risks are tilted towards a more aggressive policy package. It would not be the first time that Mario Draghi over-delivers, although this time could prove more challenging given the (very) high market expectations, the resistance from the hawks, and the need to save some ammunition for later. In this note we review the ECB’s options if it were to surprise.

In our view, the ECB’s dovish stance reflects a fundamental shift, with major implications for the economy and markets. In particular, the Governing Council’s growing focus on core inflation means their dovish bias is likely to remain in place into 2016 despite headline inflation bouncing back on energy-related base effects. Therefore, if the ECB does not deliver on all fronts on Thursday, it will likely signal that it retains ammunition for later. In other words, any market disappointment might only prove short-lived.

Meanwhile, technicalities also matter. The implementation of negative rates (with or without exemptions) in relation to asset purchases (with or without a yield threshold) will largely influence their impact on the banking system and the economy. Any larger-than-expected expansion in asset purchases would imply greater technical constraints due to (German) asset scarcity, which would probably force the ECB to adjust QE modalities accordingly.

Option 1: A bigger rate cut

A deposit rate cut may have become the least controversial easing measure, to some extent by default (because QE is still strongly opposed by some Governing Council members) and for the wrong reasons (no longer as the appropriate response to an “unwarranted monetary tightening”). It may therefore be the ECB’s first port of call to surprise.

The market has now priced in a larger than 10bp deposit rate cut for December, probably around 15bp depending on the assumptions made for the spread between the deposit and the main Refi rate. We believe that the ECB would need to cut by at least 20bp this week to surprise the market while leaving the door open to more cuts in 2016.

Recent developments suggest such a surprise is indeed possible. Reuters ran a story last week claiming that the ECB was considering changing the way it applies negative deposit rates to commercial banks’ reserves, including

through a two-tiered system for bank charges by which the amount of excess liquidity subject to the negative deposit rate would be limited, possibly depending on each bank’s cash position with the ECB on their current account and deposit facility. The idea would be to mitigate the adverse consequences of more negative rates on cash-rich banks which are largely based in core countries. The lower the deposit rate, the larger the implementation constraints and the higher the chances that the ECB has to make some technical changes eventually, possibly later in 2016.

As we noted previously[1], any such two-tiered system may bear similarities with those in place in Denmark, Switzerland or Sweden, where exemptions to negative rates have been introduced in different ways via fixed (e.g., a multiple of required reserves which are not subject to negative rates) or individual thresholds (e.g., taking into account each bank’s activity in interbank market). In the euro area, with excess liquidity well above EUR500bn, and set to rise much further as QE continues, the potential introduction of current account limits on top of the 1% required reserves is unlikely to have any significant impact on short-term rates. Put differently, excess liquidity will remain ample enough for the ECB to set a higher limit on current accounts exemptions without having too large an influence on short-term rates, although this may come with distortions across countries.

More importantly, this story suggests that the ECB is considering cutting rates by a larger amount than expected by the consensus.

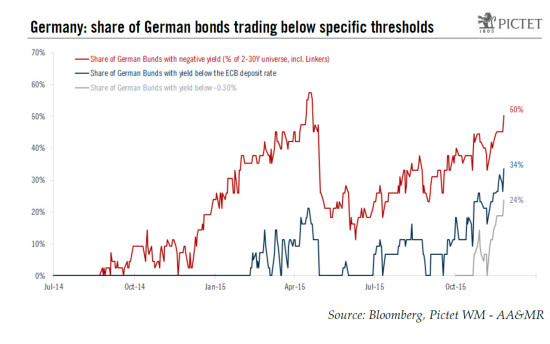

Lastly, it remains unclear what the ECB will do with the threshold (floor) on QE purchases, currently set at the deposit rate (-0.20%). Expectations of ECB easing have pushed bond yields lower, raising the share of debt securities in the QE universe that are trading below the deposit rate, or even below -0.30% (see chart below). Unless the ECB removes the threshold altogether, which looks politically sensitive[2] but not impossible, a deposit rate cut will not necessarily increase the QE universe as the curve will adjust to both the size of the cut and the ECB’s communication in terms of future cuts.

Option 2: A larger QE expansion

The ECB can expand its QE programme in duration and/or in size with similar consequences in terms of cumulated asset purchases. That said, the higher the pace of monthly purchases, the larger the market impact, given concerns over (German) asset scarcity. On the other hand, a lengthening of the programme beyond September 2016 is largely priced in and somewhat irrelevant given the de facto open-ended nature of QE, which is intended to run “beyond September 2016 if necessary” and, “in any case”, until the ECB sees “a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation”.

Using ECB’s own elasticities, we had previously estimated that each 0.1 percentage point deviation from the inflation target would require between EUR125bn and EUR250bn in additional asset purchases. Assuming the staff lowers their median projection for 2017 HICP inflation to 1.6%, then the ECB would have to add up to EUR750bn to its QE programme under conservative assumptions:

- A 12-month extension at the current EUR60bn monthly pace until September 2017 (rather than 6 month under our baseline) would result in EUR720bn in additional asset purchases.

- A similar goal could be achieved using a 6-month extension combined with a EUR25bn increase in the pace of QE, to EUR85bn a month, resulting in a EUR735bn total boost. Lastly, a 9-month extension and a EUR10bn monthly increase would amount to a EUR720bn boost.

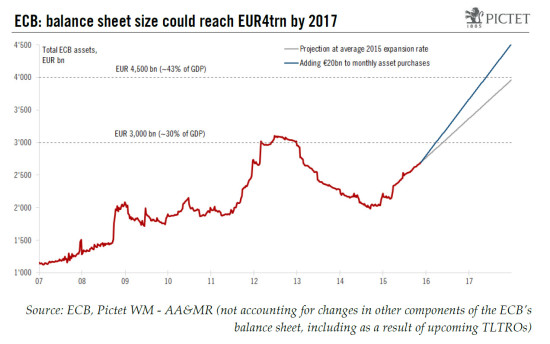

As a result, the ECB could see its balance sheet increase from EUR2,700bn at the moment, or around 26% of euro area GDP, to close to EUR4,000bn by 2017, or 43% of GDP (see chart below). Incidentally, this would push ECB QE to levels similar to the experience of the Fed or the BoE.

Option 3: Broader and more flexible asset purchases

While not the most spectacular aspect of QE, the composition of asset purchases matters a lot for markets and the real economy. The ABSPP programme is an obvious example, with very small volumes potentially

having an amplified effect on banks’ balance sheets. When it comes to public debt purchases (PSPP), the larger the expansion in size, the higher the pressure on the ECB to provide increased flexibility, in order to ensure a smooth implementation of the programme.

Some options are unlikely to face a strong resistance within the ECB, including a potential broadening of asset purchases to include local and regional debt (especially relevant in Germany), or (semi-)corporate debt, as suggested by recent press reports. There are other debt securities eligible as collateral for refinancing operations but not for QE, including bank loans, but it could prove too early for such an aggressive change in QE composition. Needless to say, buying Non-Performing Loans or equities would be even more controversial.

Meanwhile, the ECB could decide to increase the issue limits for QE again, which were raised from 25% to 33% in September, at least for the best rated sovereign bonds. This would also provide a meaningful boost to the QE universe while fuelling market expectations of future QE expansions.

The biggest bazooka on that front would be an explicit deviation from asset purchases based on ECB’s capital keys towards a more periphery-friendly rule, e.g. based on outstanding marketable debt. The ECB has hinted at targeted deviations in some specific cases initially, including in the small EMU countries with not enough debt outstanding, via “substitute purchases”. A bolder shift cannot be ruled out, in our view, although perhaps not until later in 2016.

[1] See question 9 of our Q&A on negative rates.

[2] The general idea being that the deposit rate at which the ECB remunerates (or taxes for that matter) bank reserves can be seen as a proxy for the ECB’s financing cost. If the ECB were to buy securities with a yield below this threshold, it could lose money on the operation, although the reality of central bank accounting is much more complex.