Rejection of the government-backed constitutional referendum opens up a period of uncertainty for the Italian economy and financial system, but ECB’s continued dovishness will provide support.The Italian referendum on Senate reform was rejected on 4 December by a surprisingly wide margin (59% versus 41%) on high voter turnout. In the short run, the main risk is that rejection of the government-backed referendum will render a market-based recapitalisation of the Italian banking sector more difficult.Italian banks will remain under considerable pressure. Adding to the profitability concerns that beset them, Italian banks could end up having to post more collateral to keep ECB funding should Italy’s sovereign rating be downgraded, for example.But as of Monday financial markets were not in panic mode. The European Central Bank is unlikely to make any specific response to the Italian vote. The ECB should not and will not be involved in the management of market volatility triggered by political events. For now, the ECB will front-load its monthly asset purchases via quantitative easing (QE) as it has already signalled in order to allow for a pause between 22 December and 30 December. But if sovereign spreads widen more significantly than expected as we move toward the end of the year, then the ECB could reassess the situation ahead of its 19 January 2017 meeting.

Topics:

Frederik Ducrozet and Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Italian politics, Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

Rejection of the government-backed constitutional referendum opens up a period of uncertainty for the Italian economy and financial system, but ECB’s continued dovishness will provide support.

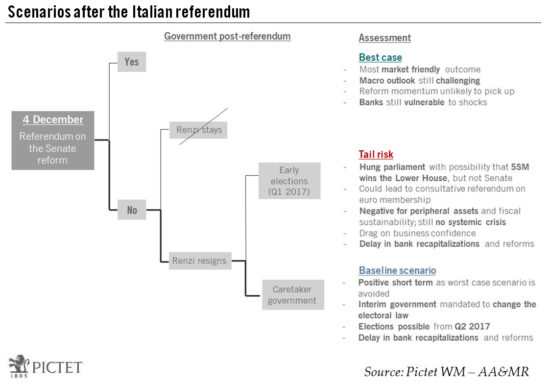

The Italian referendum on Senate reform was rejected on 4 December by a surprisingly wide margin (59% versus 41%) on high voter turnout. In the short run, the main risk is that rejection of the government-backed referendum will render a market-based recapitalisation of the Italian banking sector more difficult.

Italian banks will remain under considerable pressure. Adding to the profitability concerns that beset them, Italian banks could end up having to post more collateral to keep ECB funding should Italy’s sovereign rating be downgraded, for example.

But as of Monday financial markets were not in panic mode. The European Central Bank is unlikely to make any specific response to the Italian vote. The ECB should not and will not be involved in the management of market volatility triggered by political events. For now, the ECB will front-load its monthly asset purchases via quantitative easing (QE) as it has already signalled in order to allow for a pause between 22 December and 30 December. But if sovereign spreads widen more significantly than expected as we move toward the end of the year, then the ECB could reassess the situation ahead of its 19 January 2017 meeting.

However, political uncertainty and banking concerns will only reinforce the ECB’s long-term dovish bias. At its Thursday meeting, we still expect the ECB to announce the extension of QE by six months, until September 2017, with the same monthly pace of asset purchases of EUR80 billion per month. We also expect the ECB to make a number of changes to QE’s technical parameters which would add to the programme’s flexibility and allow it to run into 2018, if needed.

Prime minister Matteo Renzi has announced his resignation. But snap elections seem unlikely. Instead, the President of the Republic is likely to call for a temporary government to be formed tasked with amending the new electoral law and approving the 2017 budget.

A ‘No’ vote has limited direct impact on the Italian economy, at least in the short term, but a larger indirect impact. A prolonged period of political uncertainty could dent consumption and investment prospects in Italy, hurting an already fragile and modest recovery. Moreover, higher government bond yields (even if the ECB’s monthly asset purchases continue to provide support) could put sovereign debt sustainability at risk. Current nominal GDP growth of around 2% (in Q2 2016) is not high enough to offset any large, sustained increase in average borrowing costs. Thus, the macroeconomic outlook is likely to remain challenging in the months ahead.