In times of crisis, governments have a tendency to overcompensate for risk. This tendency may be in the public’s best interest, but it could also serve broader governmental interests. The public and government’s interest are not always one and the same. After the September 11 attacks, a bipartisan Congress enacted the disastrous USA PATRIOT Act (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act) in an alleged attempt to stop terrorism. After the 2008 financial crisis, the progressive Congress implemented Dodd-Frank, which dramatically expanded federal regulatory authority over the financial sector. During today’s novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, legislators are contemplating similarly

Topics:

Mitch Nemeth considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

In times of crisis, governments have a tendency to overcompensate for risk. This tendency may be in the public’s best interest, but it could also serve broader governmental interests. The public and government’s interest are not always one and the same.

In times of crisis, governments have a tendency to overcompensate for risk. This tendency may be in the public’s best interest, but it could also serve broader governmental interests. The public and government’s interest are not always one and the same.

After the September 11 attacks, a bipartisan Congress enacted the disastrous USA PATRIOT Act (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act) in an alleged attempt to stop terrorism. After the 2008 financial crisis, the progressive Congress implemented Dodd-Frank, which dramatically expanded federal regulatory authority over the financial sector. During today’s novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, legislators are contemplating similarly disastrous measures. Some politicians have called for the nationalization of the medical supply chain, while others propose draconian quarantining measures that could result in the expansion of government surveillance.

Crises often provide the public with a useful case study for understanding how systems can operate under stress, which is why some institutions are “stress tested” in times of peace and prosperity. Interestingly enough, the federal government conducts these sorts of national security exercises on a regular basis; however, presidential administrations, past and present, have largely ignored warning signs. There is even evidence that the government downplayed the warning signs of the inevitability of the September 11 attacks.

History would have us believe that government is not adept at formulating the necessary strategies to confront crises, but governments are simply comprised of people. People are inherently imperfect, and it is incredibly difficult to adequately address risks of these proportions.

We are in uncertain territory during this pandemic. This virus, as its name implies, is novel. We lack adequate information about its transmissibility, mortality rate, degree of criticality, and treatment. As the Wall Street Journal reports, “Uncertainty makes it impossible to weigh costs and benefits, such as whether reducing the spread of a virus is worth the cost of an economic shutdown.” This feeling of uncertainty has thoroughly resulted in a “tsunami of negative news” by the media, which has in turn influenced politicians to act irrationally. Former Secret Service agent and Fox News contributor Dan Bongino has referred to some in the media as “hysteria merchants” and “panic salesmen.” This feeling of insecurity is precisely why I wrote about the need to refrain from exaggerating “the novelty of our situation.”

Measures Proposed

Some elected officials and media pundits have been promoting the hysterical notion that we can either implement draconian (national) lockdown measures on both the economy and individuals or be complicit in the mass death of millions. This line of binary thinking has become all too common, but it is surely no way to govern a nation, let alone a nation the size of the United States (roughly 320 million people). Given the overwhelming diversity of our population and geography, it is prudent to evaluate the situation on a state-by-state basis, which is precisely why the US’s political structure—even after decades of centralization— still relies on the principles of federalism. To mitigate the risk of exposing mostly unaffected populations to “hot-spots,” public health agencies and professional medical associations could propose some base measures for states to implement, such as ensuring that individuals do not unduly interact outside of maintaining essential services.

As of March 25, more than half of all coronavirus cases have occurred in just four states (New York, New Jersey, Washington, and California). The question remains: what to do to ensure that the growth in the number of cases is not exponential? Some lawmakers seek indefinite lockdowns at the national level, while others prefer a more targeted approach. One of the questions we should immediately ask is what authority or powers do the federal government have and what authority are we, the people, willing to let it have?

Federal lawmakers are confined to measures that are arguably within the bounds of the United States Constitution and within legal precedent. Citizens around the world are enduring the full brunt of their leaders “never letting a crisis go to waste.” Some politicians have engaged in a bevy of civil liberty–infringing responses, such as mass surveillance techniques, enforced lockdown measures, restrictions on movement, and the closure of public facilities including places of worship.

The United States has been comparatively safe from autocratic tendencies at the federal level—compared, that is, to many foreign regimes—with officials offering recommendations rather than explicit mandates. For example, President Trump has sought more targeted measures to lock down so-called hot spots affected by the virus. Critics have derided this as putting money above public health, but as economist Paul Romer writes, “we need to shift within a couple of months to a targeted approach that limits the spread of the virus but still lets most people go back to work and resume their daily activities.” Romer rightfully acknowledges that if Treasury secretary Mnuchin’s prediction of 20 percent unemployment comes true, the economy as we know it may fail.

No Need to Nationalize the Medical Supply Chain

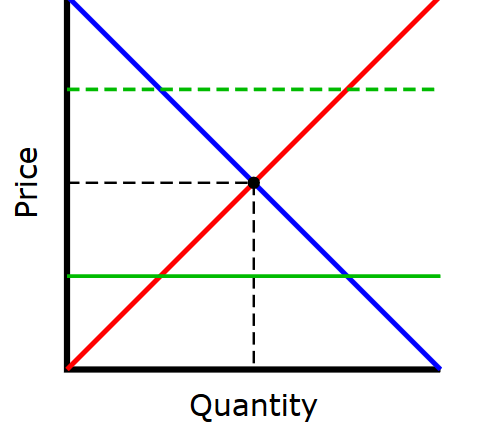

Rather than nationalizing the medical supply chain to “improve distribution of equipment,” public health and emergency management agencies could assist states by connecting states and localities to medical equipment producers and distributors on an as-needed basis. This would ensure that states take the lead in determining which medical supplies are necessary given their levels of viral cases. This facilitation would ensure that states with more novel coronavirus cases receive adequate supplies until supply can meet demand.

Nationalization of the supply chain, on the other hand, would distort the price signals present in a free enterprise system. As Jon Miltimore writes, “No single producer and central authority can possibly know what is most needed in a given economy consisting of millions of people and products. We overcome this problem by relying on information that comes from price signals.” Profit-seeking entrepreneurs will enter to meet the demand, just as Elon Musk has proposed to do.

Private enterprise is mobilizing at levels not seen since World War II to combat the “invisible enemy,” as President Trump calls it. Since private businesses are voluntarily working to supply healthcare workers with needed resources, President Trump has been hesitant to enforce the Defense Production Act. While private enterprise works with government agencies to boost supply, governments around the world are “imposing massive closures on schools, travel and gathering places, and barring many workers from going to work.” These limits on freedom are troubling but expected.

Mass Surveillance Is Not the Answer Either

Wartime measures are being modified to combat this pandemic. Some foreign lawmakers have proposed and implemented mass surveillance measures to track infected patients. For example, the Israeli government recently passed a law allowing the Shin Bet, or Israel Security Agency, to utilize cellphone location data to “track down the persons that had contact with known infected hosts, and then notify them via SMS about the next steps they must take.”

The White House has proposed partnering with American technology companies such as Facebook and Google to use “geolocation data for disease tracking.” Perhaps even more worrisome, the White House has initiated conversations with these companies over how to limit the spread of misinformation during this pandemic, which could lead to censorship.

There may be potential economic benefits to tracking the location of infected Americans. If we can properly assess the spread of the virus, then parts of the country could reopen, assuming the virus can be contained. Such data may inform government decision-making, but government should not have access to geolocation data of individuals, especially if it is not deidentified. If country-specific surveillance is not sufficiently frightening, there has been talk about “an international mobile tracing scheme” to enable “authorities to monitor movements and potentially track the spread of the disease across borders.”

While this pandemic continues, the public must ensure that any infringements “in the public interest” do not last beyond this crisis. Governments have a tendency to continue to find new justifications for old war powers. The Guardian, a progressive outlet, writes, “As we witnessed with the authoritarian reactions to 9/11, emergency violations of civil liberties are not easily rolled back, and often aggregate over time.” At the Financial Times, Yuval Noah Harari outlines the citizen empowerment needed during this pandemic. He writes, “When people are told the scientific facts, and when people trust public authorities to tell them these facts, citizens can do the right thing….A self-motivated and well-informed population is usually far more powerful and effective than a policed, ignorant population.”

Mass surveillance in the name of public health, nationalization of industry, and legally enforced quarantine measures—these are all very real possibilities in the United States. This crisis has provided policymakers or thought leaders the opportunity to demonstrate their true character while allowing everyday Americans to display their entrepreneurial spirit. Unlike past economic crises, this public health crisis is a government-mandated shutdown of “nonessential business.”

Conclusion

As the novel coronavirus began infecting Americans, some industries and businesses voluntarily closed operations to protect the public health. Other industries and businesses followed suit as a result of CDC and other public health expert guidance. To manage the shock to the medical supply chain, private enterprise has mobilized en masse to fill the gap between production and demand. As free enterprise mitigates the public health risks of the virus, government should use this opportunity to learn that the best path forward is to provide leadership and guidance rather than coercion. Government may be useful in providing oversight during this pandemic, but we cannot let the cure be worse than the problem.

Drastic measures are less necessary when businesses and individuals voluntarily cooperate to combat a public health crisis. If this case study can teach one lesson, it is that humanity can solve problems when given proper incentives, making coercion unnecessary. This is largely why the White House has not enforced the Defense Production Act to coerce businesses into building up the medical supply chain. Additionally, technology companies such as Facebook and Google voluntarily provide information to nonprofits and public health researchers so that they can provide adequate insight.

Although some would like to blame capitalism for the early missteps in the federal response to the virus, the opposite is true. It was federal public health regulators who hampered the private sector response to this crisis. To ensure that the United States moves past this pandemic, we must take an approach that minimizes government infringements of civil liberties; we must also maximize the incentives of private businesses and individuals who want to assist in our efforts to combat this “invisible enemy.”

Tags: Featured,newsletter