In this note we look at the drivers of the ECB's staff upbeat inflation projections. We find that the ECB relies to a large extent on a further pass-through from unconventional measures. In a previous note focusing on euro area consumer prices, we looked at recent trends in core inflation and came to the following conclusions: Most indicators are consistent with a gradual increase in underlying inflation in 2016, albeit with a weak momentum and downside risks. The ECB will monitor core prices very closely in 2016, looking for potential second-round effects from low energy prices, in particular. Although we expect HICP inflation to gradually rise towards the 2% target by 2018, risks are tilted to the downside relative to ECB staff projections (core inflation at 1.6% in 2017; headline inflation at 1.7%). In this note we look more specifically at the drivers of those upbeat ECB staff projections. We find that the ECB relies to a large extent on a further pass-through from unconventional measures (QE and TLTROs), including a further depreciation in the trade-weighted EUR that may not fully materialise. Any disappointment in core price data would likely force the ECB to respond with additional monetary stimulus, including another deposit rate cut and/or QE expansion, by Q2 2016 in our view.

Topics:

Frederik Ducrozet and Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

In this note we look at the drivers of the ECB's staff upbeat inflation projections. We find that the ECB relies to a large extent on a further pass-through from unconventional measures.

In a previous note focusing on euro area consumer prices, we looked at recent trends in core inflation and came to the following conclusions:

- Most indicators are consistent with a gradual increase in underlying inflation in 2016, albeit with a weak momentum and downside risks.

- The ECB will monitor core prices very closely in 2016, looking for potential second-round effects from low energy prices, in particular.

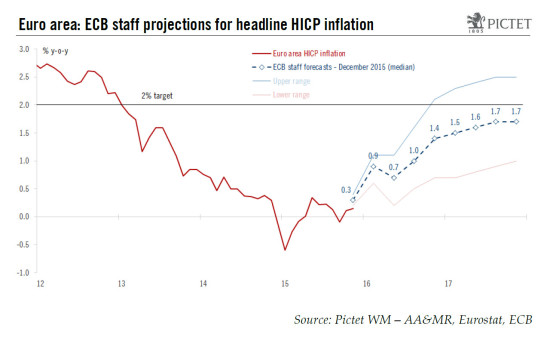

- Although we expect HICP inflation to gradually rise towards the 2% target by 2018, risks are tilted to the downside relative to ECB staff projections (core inflation at 1.6% in 2017; headline inflation at 1.7%).

In this note we look more specifically at the drivers of those upbeat ECB staff projections. We find that the ECB relies to a large extent on a further pass-through from unconventional measures (QE and TLTROs), including a further depreciation in the trade-weighted EUR that may not fully materialise.

Any disappointment in core price data would likely force the ECB to respond with additional monetary stimulus, including another deposit rate cut and/or QE expansion, by Q2 2016 in our view. The ECB staff will update their projections in March 2016, extending them through 2018, while QE modalities will be reviewed again in the spring.

Deflation risk is “off the table”, then what?

We agree with ECB President Mario Draghi’s view that deflation risk is “off the table”. At the aggregate euro area level, there has been no evidence of consumers postponing their purchases based on expectations that prices would fall in the future. Most likely, households have been either unable (because of income constraints) or unwilling (because of precautionary savings motives) to spend as much as they would have otherwise.

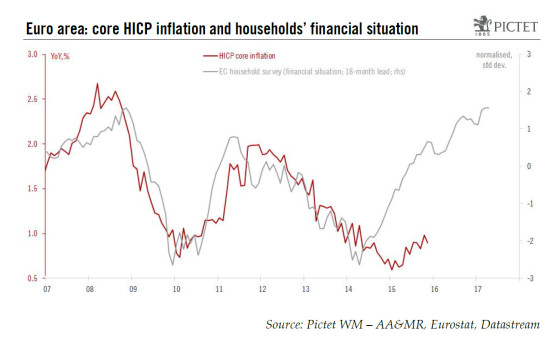

The chart below shows one of our favourite “No Deflation” relationships, with the improving financial situation for households largely inconsistent with a further decline in core inflation. A similar conclusion could be drawn from other business surveys of labour conditions, or expectations of broader economic conditions.

Rather, the key question facing the ECB in 2016 is how fast and how far (core) inflation can rise in the current macro environment.

On the bright side, a healthy domestic recovery should help. We expect another strong increase in private consumption, a pick-up in investment spending fuelled by bank credit and a steady rise in employment, all helping to reduce output from current levels (which the European Commission estimates at -1.8% in 2015). Domestic conditions are in place for sustained wage growth and for core inflation to rise in the next couple of years — albeit gradually due to remaining deleveraging pressures. We currently forecast core HICP inflation at 1.1% in 2016 (from 0.8% in 2015), rising to 1.3% on average in 2017.

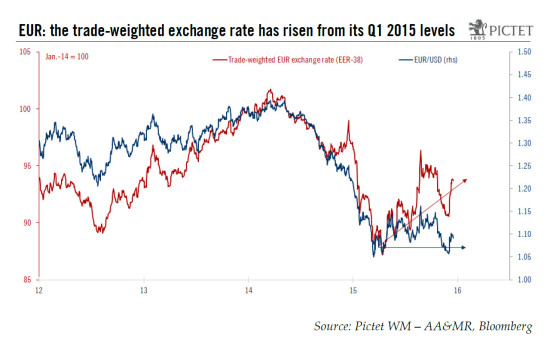

We see two main downside risks to (core) inflation over the medium-term. First, Emerging Markets growth could get worse before it gets better, exporting further disinflationary pressures to Developed Markets. Second, ECB staff projections rely heavily on the positive pass-through from unconventional policy measures to inflation (QE and TLTROs), especially via the FX channel. While we forecast some further EUR/USD weakness in 2016, the euro’s depreciation on a trade-weighted basis could be more limited. In other words, the lagged effect of past currency depreciation could fade in 2016. Second-round effects from lower commodity prices might weigh, too.

The medium-term outlook for core inflation: solving the ECB’s (apparent) inconsistency

The latest ECB staff forecasts published in December were revised lower in terms of headline inflation (from 1.7% to 1.6% in 2017), but to a lesser extent in terms of core inflation. The median projection for HICP excluding energy and food was left unchanged at 1.6% in 2017, although the pace of normalisation was revised slightly lower.

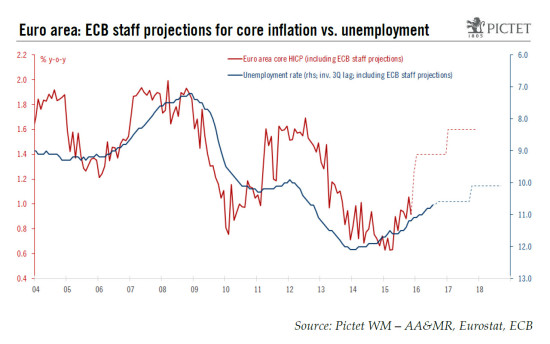

Importantly, these relatively upbeat staff forecasts for core inflation appear somewhat at odds with the ECB’s macro assumptions on the output gap and unemployment, as show in the chart below.

One reason for this apparent inconsistency between core HICP and unemployment projections may be related to the ECB’s assumptions in terms of the (lagged) pass-through of unconventional monetary measures (QE and TLTROs) on inflation through various channels. Indeed the staff changed their methodology in March 2015 in order to explicitly account for those effects of balance sheet expansion, not only to the extent that they had already affected market-based variables (FX, interest rates), but also their future effects via the “portfolio rebalancing channel, certain expectational channels and real-financial feedback loops”.

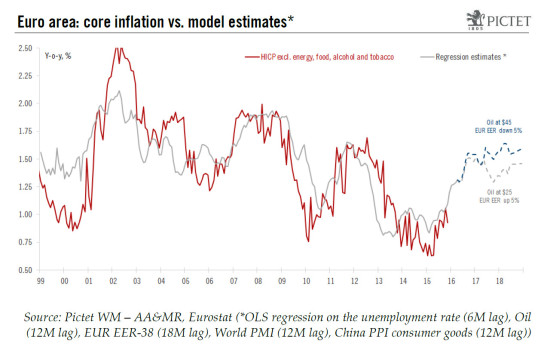

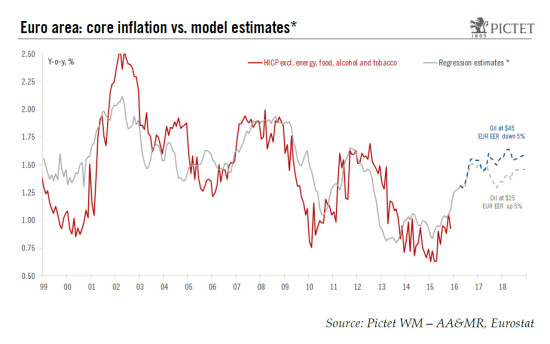

In practice, we know little about the ECB’s internal models and we suspect that a large part of the QE pass-through is modelled via the currency transmission channel*. Our findings confirm this suspicion. We run a simple, Ordinary Least Squares regression for core HICP inflation against the following variables:

- the euro area unemployment rate (with a 6-month lag);

- the EUR nominal effective exchange rate against a broad basket of 38 currencies (with a 18-month lag);

- oil prices (with a 12-month lag);

- the World manufacturing PMI index (with a 12-month lag);

- the Chinese Producer Price Index (PPI) consumer goods inflation rate (with a 12-month lag).

Despite a simple specification, the model estimates are fairly robust (R-squared of 70%) and all explanatory variables are statistically significant. The time lags allow for out-of-sample forecasts using our own projections for the unemployment rate as well as various assumptions for oil prices and FX developments.

The output chart below (also on the front page) illustrates our main findings:

- ECB staff projections for core inflation appear consistent with their forecasts for the unemployment rate or output gap once accounting for the lagged effects of currency depreciation and controlling for “global inflation factors” encapsulated in the World PMI index and Chinese PPI;

- The lagged effects of currency depreciation are expected to fade later in 2016, unless the trade-weighted EUR falls by a further 5% and oil prices rebound to around $45 per barrel.

The bottom line is that the ECB staff projections rely on optimistic assumptions in terms of global inflation and currency effects as well as, more generally, the pass-through from unconventional monetary policy measures. Even though we forecast core inflation to rise gradually in the next couple of years, we see downside risks relative to ECB staff projections, keeping the pressure on the Governing Council to respond to any further disappointment in the data. Therefore we see the risks tilted towards more, not less, monetary stimulus in H1 2016.

It looks less clear to us which tool the ECB would favour. Another deposit rate cut would be on the table in the event of a more significant EUR appreciation, say to above 1.15 against the USD. That said, if currency strength leads to another downward revision to ECB staff projections for inflation, then the appropriate answer should be a further QE expansion, this time possibly via an increase in the monthly pace of asset purchases (from EUR60bn currently) as well as technical changes to QE modalities (including higher issue/issuer limits, broader substitute purchases or even a deviation from capital keys weights) aimed at a smoother programme implementation.

* Note that the ECB staff projections are based on the assumption of broadly stable FX over the forecast horizon (EUR/USD at 1.09 and EER-38 stable at early November 2015 levels). However, the staff may well include some further depreciation in their models as part of those indirect effects of QE.