Twenty-fifteen was an important yet completely misunderstood year. The Fed was going to have to become hawkish, according to its models, yet oil prices crashed and the dollar continued to rise. Both of those things were described as “transitory” by Janet Yellen, and that they were helpful or positive (rising dollar means cleanest dirty shirt!), but domestically American policymakers’ clear lack of conviction and courage about that rate hike regime showed otherwise. It wouldn’t be until December 2015 that Yellen finally got on with it – and then promptly paused for an entire year (until December 2016) while explaining nothing about anything before or after. The US economy did not fall into recession, which is one key source of confusion. For most of the public,

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, balance sheet capacity, bonds, currencies, Dollar, economy, EuroDollar, exports, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, global dollar shortage, global reserve currency, global trade, harry markowitz, imports, Markets, newsletter, var

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Twenty-fifteen was an important yet completely misunderstood year. The Fed was going to have to become hawkish, according to its models, yet oil prices crashed and the dollar continued to rise. Both of those things were described as “transitory” by Janet Yellen, and that they were helpful or positive (rising dollar means cleanest dirty shirt!), but domestically American policymakers’ clear lack of conviction and courage about that rate hike regime showed otherwise.

It wouldn’t be until December 2015 that Yellen finally got on with it – and then promptly paused for an entire year (until December 2016) while explaining nothing about anything before or after.

The US economy did not fall into recession, which is one key source of confusion. For most of the public, other than a scary hiccup in stocks first in August of that year (preceded by “devaluation” in CNY just a few weeks before) and then again to begin 2016, it didn’t seem all that unusual. Lots of noise about “overseas turmoil.”

But, as I wrote in June 2015, warning about what was already unfolding:

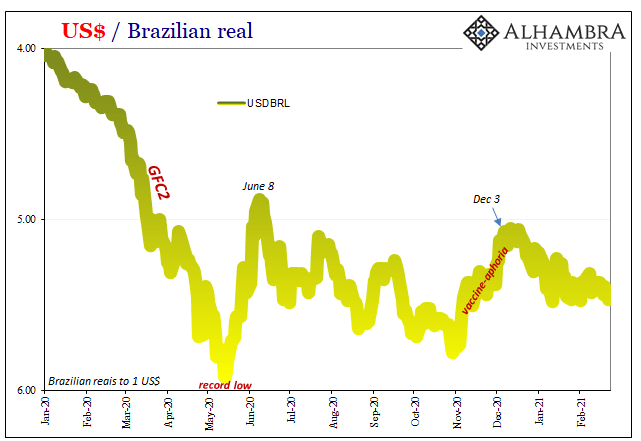

To a great extent, Americans are both sheltered and wholly unaware, but the rest of the world is very much alerted to the continued downside of the eurodollar standard. Stocks may be at or near record highs (though broader stock indices, such as the NYSE composite, have gone nowhere since the “dollar” started to rise), but Brazil is in a state of total economic and financial chaos while China flirts with what was never thought possible (growth at Great Recession levels, a massive housing imbalance and now a stock bubble that in some ways puts the dot-coms to shame). There was a “dollar” system somewhat in place, largely before the middle of 2013, which supported all those but no longer does.

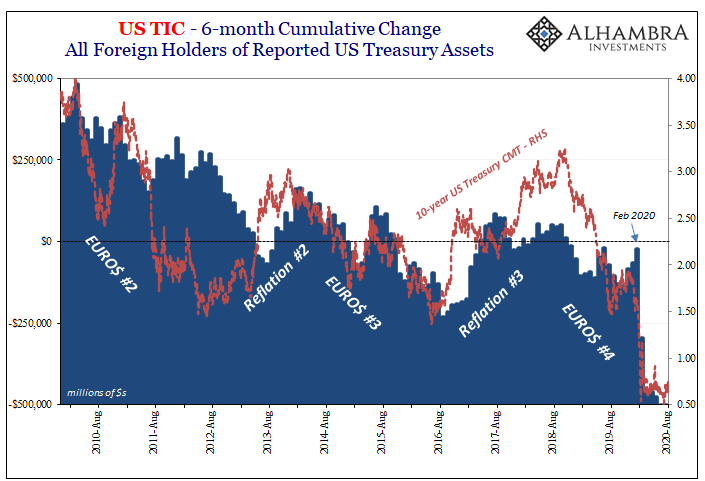

| A near miss or near recession in the US, absolute chaos and – in lots of places – nasty depression around the rest of the world. The global economy had been very synchronized long before 2017’s blusterous slogan to that effect; what’s always been different is the varying degrees to which that same underlying eurodollar problem wreaks first currency then economic havoc.

If there is any privilege to the dollar’s denomination status as a reserve (with the actual functions of that reserve carried out by the eurodollar system, not the dollar), this is it. There are times like Euro$ #3 (2014-16) as well as the pre-COVID downturn during Euro$ #4 when, as the title of my ancient article reads, Americans can be sheltered and wholly unaware. Quite helpfully, or not, I described much of this mysterious substance in the same essay; though they may be called dollars and correctly identified as eurodollars, there just ain’t any currency at least none readily recognizable:

While total bank reserves became irrelevant (and actually remain so), the “global dollar short” exploded as a combined expression of banking hubris about risk management (recency bias) and the interplay of Greenspan-type faith over smoothing out large historical variations in asset prices… By August 2007, while bank reserves were just $8 billion or so, the global dollar short had exploded to $2 trillion, $5 trillion, perhaps as much as $10 trillion! That all came from new forms of money-like behavior and the liquid ability to trade risk parameters. That meant the disruptions in 2007 were far harder for traditional monetary mechanics to reach and alleviate. Again, in terms of the same example from above, a security and a paired hedge position that suddenly deviates from expected variance requires additional hedging components to bring it back in-line; absent that ability, the bank suffers a greater capital charge which has the practical effect of reducing leverage available in other parts of the balance sheet (vega and so on). That may be several steps detached from what is commonly thought of a bank run, but it is the very same pattern carried out across multiple dimensions – especially when additional hedging comes at a far higher price, or, in the worst cases of a run, is completely unavailable (as it was in the worst parts of the crisis). |

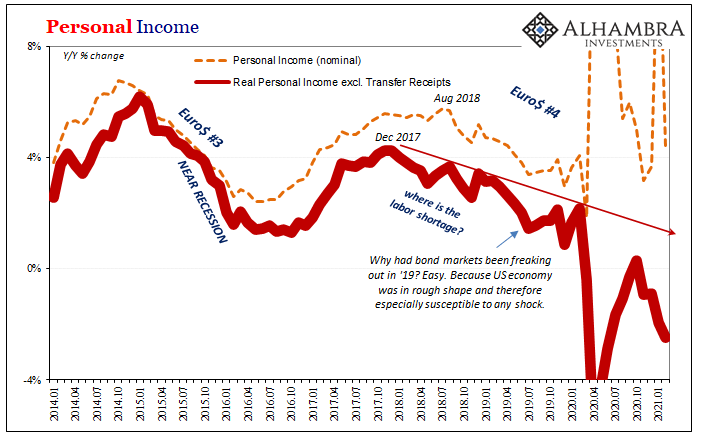

Personal Income, 2014-2021 |

| Given all that (and a whole lot more, especially concerning the role of collateral behind much of the rest), it’s exceedingly hard to get Americans to realize that ending the dollar’s regime isn’t some geopolitical loss; this isn’t a zero-sum contest. Rather, it’s a game we all lose – everyone around the world – for as much as it remains in the shadows. Global dollar shortages may emphasize the first word in that expression, but they aren’t in any way exclusive to the ex-US part of it.

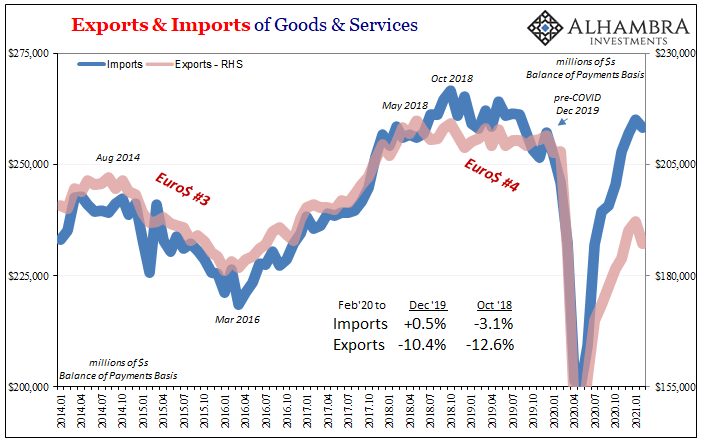

Even on the current global rebound (it’s not recovery), in 2021 the rough edges of the same discrepancies are becoming highly visible all over again. Like 2015, it’s not exactly good in the US but you should see just how it’s going outside this country. Americans are again sheltered and wholly unaware. Here’s a pretty good and clear example: The question is simply why the US economy has performed relatively better yet again (arguably using global trade values as a proxy here; imports are up on domestic demand rebounding faster and farther than foreign demand for US goods and services). Is it COVID? Not likely given how the American economy had been relatively insulated prior to corona’s arrival when compared to the globally synchronized downturn that had already pressed Europe and Japan into mild recession long before the pandemic. And it’s not as if the US’ experience during it has been all that favorable; American case counts, deaths, and lockdowns have been among the most severe. Stimulus, perhaps? CARES Act, helicopters and QE’s? Not likely, either, given that each of those things (expressed in different ways) have been used – in Europe, for example, to an even greater extent – around the rest of the world. |

Exports & Imports of Goods & Services, 2014-2021 |

| The global economy again is struggling while the US performs comparatively healthier. Ben Bernanke once tried to take credit for this (ironically, later in 2015), though this “dollar privilege” actually can account for all the instances it arises.

And it becomes self-reinforcing, one of the worst aspects shown of the chart above. Foreign economies suffer more, and as a result their dollar problems get bigger (risk) making these foreign economies suffer still more. |

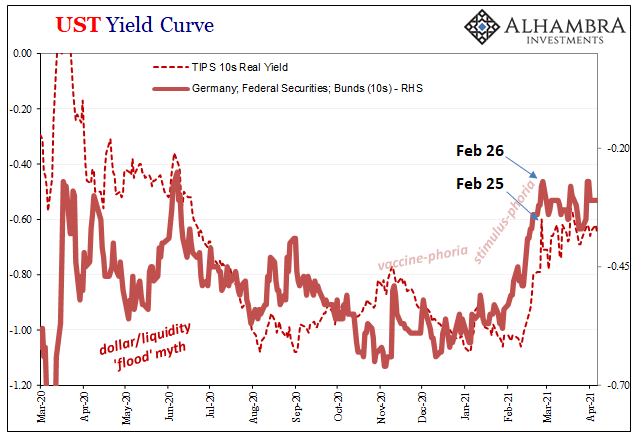

UST Yield Curve, 2020-2021 |

As I wrote nearly six years ago, the modern “currency” of balance sheet capacity is all about “risk”:

Collateral as in repo (SFTs more broadly) behave and suffer the same way. |

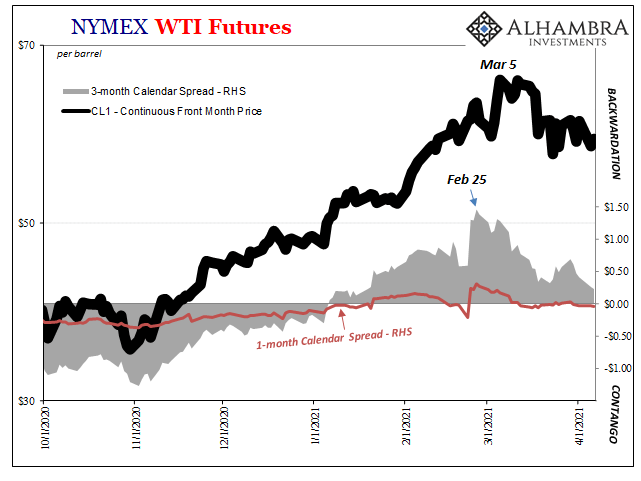

NYMEX WTI Futures, 2020-2021 |

| Cleanest dirty shirt again? Yes, but that just doesn’t mean as much as it sounds. Economic conditions might not be synchronized as in proportional levels of distress, but eurodollar “stuff” in 2021, especially since late February, sure has been. |

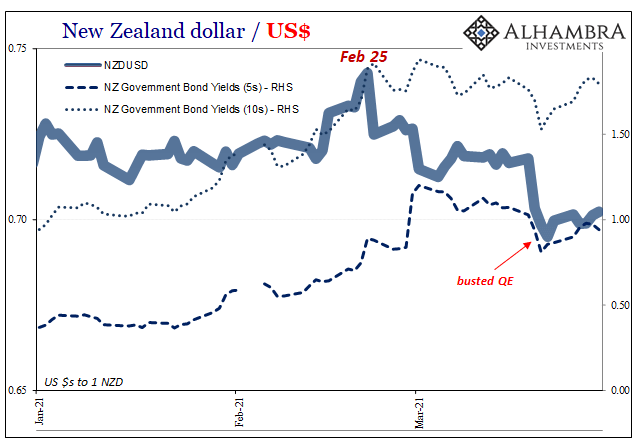

New Zaeland Dollar / US Dollar |

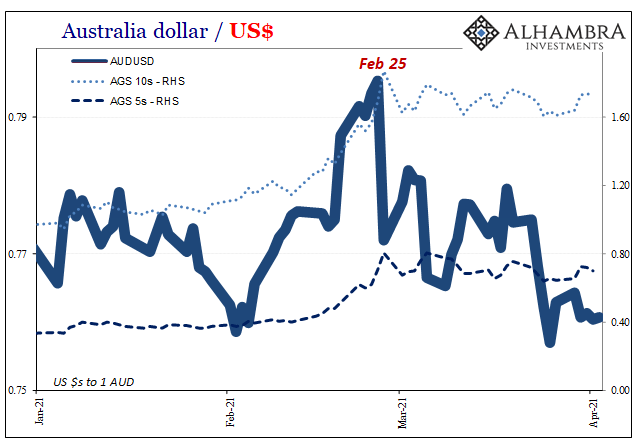

Australia Dollar / US Dollar |

Tags: balance sheet capacity,Bonds,currencies,dollar,economy,EuroDollar,exports,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,global dollar shortage,global reserve currency,global trade,harry markowitz,imports,Markets,newsletter,var