This devaluation of financial wealth–and its transformation to a dangerous liability– will reach extremes equal to the current extremes of wealth-income inequality. Financial capital–money–is the Ring that rules them all. But could this power fall from grace? Continuing this week’s discussion of the idea that that extremes lead to reversions, let’s consider the bedrock presumption of the global economy, which is that money is the most valuable thing in the Universe because the owner of money can buy anything, as everything is for sale. The only question is the price. Reversion to the mean is a statistical dynamic but it is also a human social dynamic: for example, once the social / financial / political pendulum reaches Gilded Age extremes of wealth/income

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro

This could be interesting, too:

Charles Hugh Smith writes How Do We Fix the Collapse of Quality?

Charles Hugh Smith writes Is Social Media Actually “Media,” Or Is It Something Else?

Charles Hugh Smith writes Welcome to the Circular Firing Squad

Charles Hugh Smith writes Can We Rein In the Excesses of Financialization Without Crashing the Economy?

This devaluation of financial wealth–and its transformation to a dangerous liability– will reach extremes equal to the current extremes of wealth-income inequality.

Financial capital–money–is the Ring that rules them all. But could this power fall from grace? Continuing this week’s discussion of the idea that that extremes lead to reversions, let’s consider the bedrock presumption of the global economy, which is that money is the most valuable thing in the Universe because the owner of money can buy anything, as everything is for sale. The only question is the price.

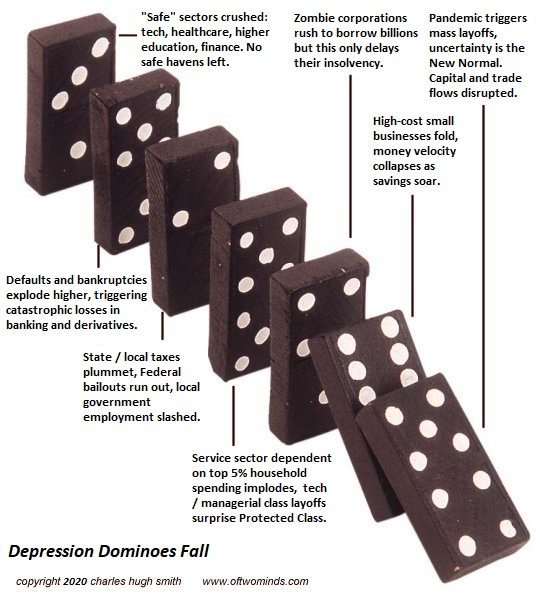

Reversion to the mean is a statistical dynamic but it is also a human social dynamic: for example, once the social / financial / political pendulum reaches Gilded Age extremes of wealth/income inequality, the pendulum swings back. The more extreme the inequality, the greater the resulting extreme at the other end of the pendulum swing.

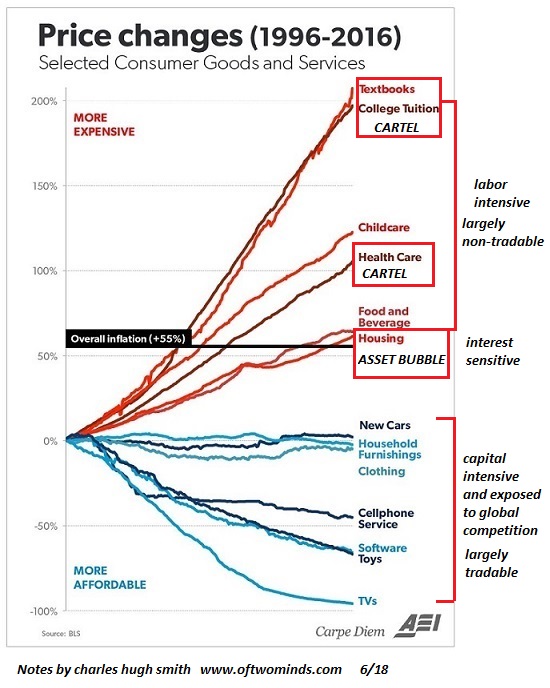

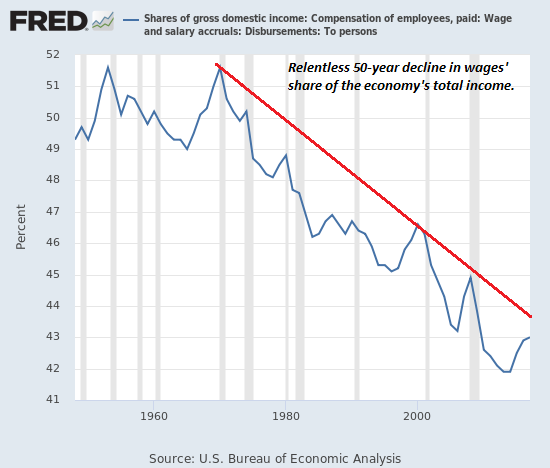

In the heyday of the postwar boom in the early 1960s, finance–banks, lending, mortgages, loans, investment banking, derivatives, futures, FX, all financial market trading, research firms, hedge funds, mutual funds, etc.–was about 5% of the economy. It now exceeds 20% of the economy, and its actual role and impact is much larger than 20%. Finance is now the dominant force in the economy in terms of wealth creation and influence.

(This parallels healthcare, which went from less than 5% of the economy to 20% in the same time span.)

While finance creates some jobs, it is essentially extractive: it produces no goods, it extracts wealth from the goods-producing economy via debt and speculation.

Thus a reversion that reduces finance back to 5% of the economy can be expected. How will this reversion to a much more constrained and modest role in the economy play out?

There is much to be said about such a complex and consequential process, but today I want to focus on one potential dynamic: the idea that social capital–our connections and loyalties to groups and other people–will become more valuable than financial wealth, i.e. “money.”

The past 45 years can be characterized as the ascendance of finance: finance rules everything. Most people would say this has been true for all of human history, but it isn’t quite so simple.

In many instances, loyalties, membership and devotion to causes far outweigh the influence of money. In periods of severe labor shortage, labor has more value that money, in the sense that labor sets the price of labor rather than capital setting the price.

This article caught my eye a few weeks ago: The Rich in New York Confront an Unfamiliar Word: No The pandemic is causing inequality to soar, but increasingly the privileged are discovering that they can’t bend the world to their will.

The wealthy are accustomed to buying whatever they want with money, and the possibility that there might be limits on the power of money is shocking to them.

The wealthy are accustomed to buying whatever they want with money, and the possibility that there might be limits on the power of money is shocking to them.

These limits might take political forms such as regulatory limits on what wealth can buy, they might take financial forms such as bans on certain speculative skims, and they might also take social forms, where people refuse to provide some good or service for cash because they’ve been reserved for family, friends or exchanges within trusted networks where membership cannot be purchased at any price.

Here is a simple example. Let’s say I have an in-law unit adjacent to my house. It’s been promised to a family member, and so when a prospective tenant offers me $1,000 a month to rent it, I decline.

In the unmoored, soulless world ruled by money, the prospective tenant reckons the “problem” (my refusal) can be solved with more money. So he offers me $1,500 a month. I decline, because the bonds of family are more important and valuable than a few more dollars.

The “problem” for the wealthy isn’t money; the “problem” is that social ties, obligations and commitments are more valuable and binding than money. The wealthy assume that “everyone has a price,” a truism proven by Jeffery Epstein, who bought his way into Harvard, MIT, etc. with bundles of cash.

But as the status quo unravels, the wealthy will discover that not everyone can be bought. Indeed, accepting a big bribe might terminate all sorts of much more valuable connections.

Thus it seems likely to me that social capital–our connections, loyalties, memberships, obligations and bonds–will become more valuable and financial capital will become not only less valuable, but an actual liability–a “Mark of the Beast” if you will.

This devaluation of financial wealth–and its transformation to a dangerous liability– will reach extremes equal to the current extremes of wealth-income inequality: in other words, an extremely-extreme extreme in which trying to buy what cannot be bought will be the path to a poverty unlike any other.

A reversal of this magnitude is considered “impossible.” We’ll see.

Tags: