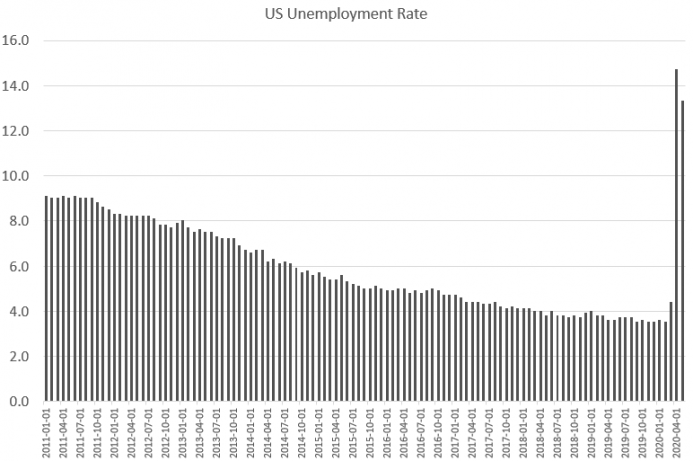

Last Friday, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released new unemployment data. The report surprised many because it showed a decrease in the unemployment rate, while many observers had expected an increase. According to the official headline (seasonally adjusted) number, the unemployment rate was 13.3 percent in May. That was down from April’s rate of 14.7 percent. This data point was seized upon by commentators who insist that there will be a “V-shaped” recovery. “The economy is fundamentally in great shape,” this narrative goes, “and everything will bounce back as soon as mandated lockdowns are lifted.” Those who support this narrative thus concluded that May’s drop in unemployment proved the “V-shaped” recovery was already underway. But it may yet be much too

Topics:

Ryan McMaken considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Last Friday, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released new unemployment data. The report surprised many because it showed a decrease in the unemployment rate, while many observers had expected an increase.

According to the official headline (seasonally adjusted) number, the unemployment rate was 13.3 percent in May. That was down from April’s rate of 14.7 percent. This data point was seized upon by commentators who insist that there will be a “V-shaped” recovery. “The economy is fundamentally in great shape,” this narrative goes, “and everything will bounce back as soon as mandated lockdowns are lifted.”

Those who support this narrative thus concluded that May’s drop in unemployment proved the “V-shaped” recovery was already underway.

But it may yet be much too early to rejoice and declare the economy on the mend.

For one, it turns out that the unemployment rate in May may have actually increased depending on how the “absent” workers are counted.

BLS economists called this a “misclassification error” and it was noted in the BLS report itself, near the end:

There was also a large number of workers who were classified as employed but absent from work. As was the case in March and April, household survey interviewers were instructed to classify employed persons absent from work due to coronavirus-related business closures as unemployed on temporary layoff….However, it is apparent | that not all such workers were so classified. BLS and the Census Bureau are investigating why this misclassification error continues to occur and are taking additional steps to address the issue. If the workers who were recorded as employed but absent from work due to “other reasons” (over and above the number absent for other reasons in a typical May) had been classified as unemployed on temporary layoff, the overall unemployment rate would have been about 3 percentage points higher than reported (on a not seasonally adjusted basis).

| In other words, it is likely that the unemployment rate was closer to around 16 or 17 percent. How much did the misclassification error affect April’s numbers? That’s not quite clear.

What we do know is that it’s rather odd to point to an unemployment rate of 16 percent and declare the economy to be roaring back or well into a “V-shaped” recovery. At this time there is no evidence at all to support such a conclusion. After all, the data that has come out since Friday’s numbers hardly points to an economy that’s roaring back. New data on initial unemployment claims released today shows that 1.5 million new workers filed for unemployment over the past week. This was hailed by some commentators as great news. Yes, this number was “good” compared to the previous eleven weeks, but it’s hardly anything to celebrate. After all, keep in mind that during the Great Recession initial claims peaked at around 960,000. So, even accounting for growth in total employment, a jobless claims number of 1.5 million is still a disaster. But this round of job losses certainly didn’t peak at 1.5 million. It peaked (hopefully) at 6.2 million in early April. |

US Unemployment Rate, 2011-2020(see more posts on U.S. Unemployment Rate=, ) |

| Thus, last week’s 1.5 million is just another 1.5 million in addition to the 40.3 million newly unemployed that have cropped up since March.

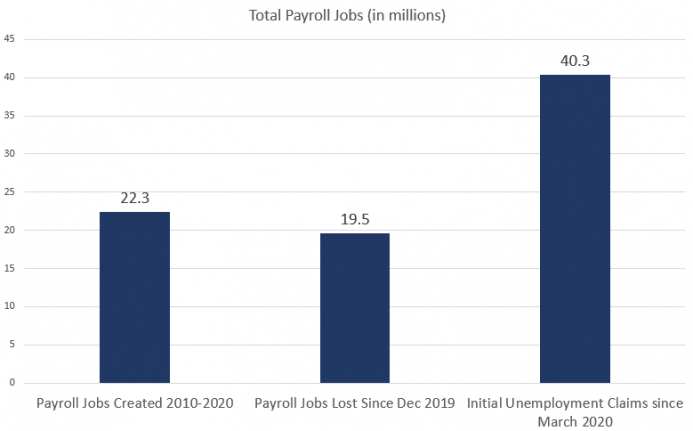

To put this in perspective, note that over the past decade the US economy has added 22 million payroll jobs, (and has lost 19.5 million jobs since the end of 2019): Basically job losses in recent months are “off the charts.” Meanwhile, in May our alleged V-shaped recovery added back 2.9 million jobs from April to May. But that’s only 7 percent of the 40 million people who filed for unemployment claims in recent months. Yes, that 2.9 million jobs is an improvement but not exactly a reason to throw a party. Here’s another way to look at the employment situation. How far below the jobs peak are we, even after May’s gains? Let’s compare to other job recovery periods. Here we see the current job losses indexed to the peak level. Using payroll jobs data we see that employment was already off peak in late 2019. |

Total Payroll Jobs, 2010-2020 |

| This may have very well been largely due to wintertime drops in employment. But, of course, total jobs then collapsed in March, and to a level far below anything we’ve seen in well over forty years:

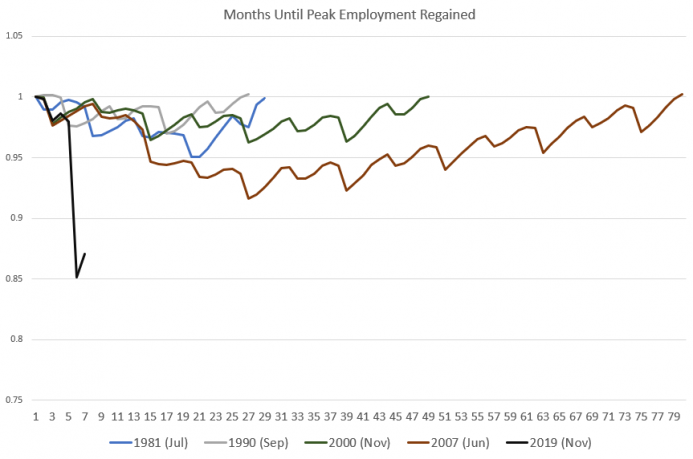

In April, total jobs were at 85 percent of peak levels. Happily, that number improved to 87 percent in May. But, it’s quite clear that we have a long way to go. Now, it’s entirely possible that job growth will completely buck the trend of the past forty years. That trend has been one in which each new round of job losses takes longer and longer to be erased. For instance, it took more than six years after the Great Recession for total jobs to reach previous peak levels. That’s compared to just 2.5 years during the early 1990s recession. So, are May’s job gains just the first part of a rapid surge of employment back toward the previous peak? Or will job gains be a long, hard slog, as they have typically been during the past twenty years? That’s unknown at this point. |

Months Until Peak Employment Regained, 1981-2019 |

But in order to have a recovery that is indeed V-shaped we’ll need to see job gains of several million with each passing month. The economy is in a very odd position, to say the least, so I’m not saying that’s impossible. But I’m also looking in vain for any evidence that such a thing is likely. After all, the economy was already weakening in late 2019, as suggested by the relaunch of QE (quantitative easing) to “stabilize” the repo (repurchase) market, and the Fed’s repeated cuts to the federal funds rate at the time.

For what it’s worth, Federal Reserve economists have already weighed in against a V-shaped recovery. As Bloomberg reports:

In updating its projections for growth and unemployment Wednesday, the Federal Reserve poured cold water on the notion that last week’s surprise jobs report signaled a sharp V-shaped recovery for the U.S. economy….The Fed’s latest economic forecasts suggest a 6.5% contraction in gross domestic product in 2020 that would take 2 years to reverse. The projection for the unemployment rate was also downbeat with a 9.3% unemployment rate at the end of the year.

Fed economists have shown no particular skill in producing accurate forecasts, but the Fed does tend to take a more optimistic and measured tone than is frequently warranted. Fed economists predicted a very fast bounceback after the Great Recession. They were wrong. And during the past twenty years Fed reports typically soothe the reader with descriptions of an economy that is “moderate” or “strengthening.” The fact that the Fed doesn’t have much good news to share suggests there isn’t much good news to share.

On the other hand, it’s not too late to put into place some policy measures that could help spur a fast recovery. But what is required is contrary to what most policymakers consider to be politically acceptable: widespread deregulation, lowering of minimum wages, and free trade. These measures would significantly reduce costs to employers and bring a real jobs bounce to those employers who adapt to the new realities of the 2020 economy.

Tags: Featured,newsletter