Central banks are prepared to take fresh measures to strengthen and extend the business cycle primarily because price pressures are below what their predecessors thought would be acceptable levels. Draghi, speaking for the ECB, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of Japan ratcheted up their concerns, which, even without new initiatives, were sufficient to drive interest rates lower. Eurozone There is no real definition of many terms economists throw around like recession or depression. The “two negative quarters of declining GDP” is not a technical definition but a rule of thumb. Ironically there weren’t recessions before the Great Depression. The end of business or credit cycles were called panics and crises. The use

Topics:

Marc Chandler considers the following as important: 4) FX Trends, Featured, Interest rates, newsletter, Surplus Capital, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Central banks are prepared to take fresh measures to strengthen and extend the business cycle primarily because price pressures are below what their predecessors thought would be acceptable levels. Draghi, speaking for the ECB, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of Japan ratcheted up their concerns, which, even without new initiatives, were sufficient to drive interest rates lower.

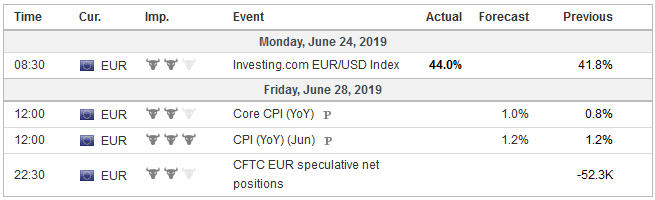

EurozoneThere is no real definition of many terms economists throw around like recession or depression. The “two negative quarters of declining GDP” is not a technical definition but a rule of thumb. Ironically there weren’t recessions before the Great Depression. The end of business or credit cycles were called panics and crises. The use of “recession” appears to have been applied to economies to distinguish the end of the business cycle from the Great Depression. Neither the US nor Europe seems to be on the verge of an economic contraction. Given a shrinking population, the Japanese economy can contract, and per capita GDP can still rise. The Bundesbank warned last week that the German economy may have contracted in Q2, but the eurozone flash composite PMI suggests the region expanded. Although the composite PMI averaged 51.8 in Q2, following a 51.5 average in Q1, GDP growth maybe half of the 0.4% in recorded in the first three months of the year. The most important data point for the eurozone next week is the flash CPI reading. Some may see it as a non-story as headline inflation is expected to remain at 1.2% and the core rate at 0.8%. Unchanged data is the story. Draghi was clear: if conditions do not improve, the ECB needs to provide more stimulus. |

Economic Events: Eurozone, Week June 24 |

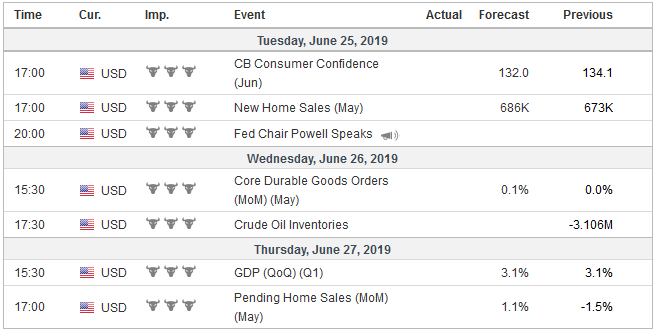

United StatesThe Federal Reserve took a different spin. The median economic forecasts were little changed but acknowledged softer price pressures. The Fed argued that it was the uncertainty around the economic forecasts that spurred the change in stance. It exited its patient mode and appears poised to pounce on signs that the economy is faltering. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP tracker puts Q2 US growth near 2.0% annualized. The US report a revised estimate of Q1 GDP on June 27. It is likely to remain a little above 3.0%, so even if the NY Fed’s GDP tracker is right and growth in Q2 is closer to 1.4%, growth in H1 has seen been above trend. Although job growth appears to have slowed, it has been enough to keep the unemployment rate at the lowest in a generation. The low participation rate likely reflects a myriad of social issues, well beyond the reach of monetary policy. The day after the Q1 GDP revisions, the government reports personal consumption expenditures. The continued jobs growth and wages growing above the rate of inflation has helped underpin consumption. Household consumption averaged a monthly increase of 0.5% a month in Q1 after 0.2% in Q4 18 and 0.3% for the entire year. After a 0.3% increase in April, consumption is expected to have firmed to 0.5%. The American consumer remains the bedrock of the economy. The year-over-year pace of the PCE deflator is likely to be unchanged, like eurozone’s CPI, though a bit higher of levels (1.5% at the headline, which is what Fed formally targets, and the 1.6% core rate). |

Economic Events: United States, Week June 24 |

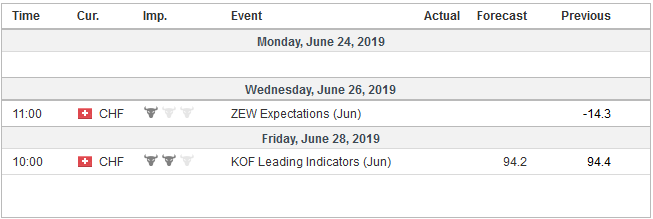

Switzerland |

Economic Events: Switzerland, Week June 24 |

The market has discounted three Fed rate cuts in H2 when there are four meetings. Some economists expect the first move to be 50 bp, though the two precedents cited began with significantly higher interest rates. Fed President Kashkari, a non-voting member of the FOMC this year, said that he advocated a 50 bp cut now. However, he failed to convince a single colleague, even Bullard who gave the first dissent under Powell’s chairmanship, in favor of an immediate cut. Nor did Kashkari convince the seven Fed officials who do agree that 50 bp of cuts may be appropriate this year.

Still, it is difficult to imagine how much more Fed easing can be discounted this year, suggesting the market may have reached peak dovishness. An insurance policy move of 25 or maybe even 50 bp is one thing but a campaign as the market has discounted into next year (frontloaded due to political considerations) is a horse of a different color.

Operating broadly under the decision-making principle of minimizing your maximum regret, the Fed wants to nurture and extend the recovery. That seems like a noble goal. However, the widespread narrative, which Fed officials themselves have helped to propagate, that the Fed kills recoveries have led to poor economic outcomes. Over the past thirty years, there have been three crises–in the vernacular, the S&L Crisis, the tech bubble, and the Great Financial Crisis. Exactly none were caused by the Federal Reserve tightening monetary policy.

To the contrary, each seems to have emanated from too lax of policy, broadly understood to include regulatory authority. Have we collectively forgot amount the insight from Hyman Minsky again? To the extent the Great Moderation of longer and flatter business cycles and low inflation is due to a structural shift market economies (rise of the less cyclical service sector, international competition, better inventory management, big business becoming more self-financing, and changing demographics), low-interest rates for an extended period of time require other (macroprudential?) tools.

In the framework I presented in my book Political Economy of Tomorrow, the underlying problem is one of absorbing surplus capital or what a Bain study called the Super Abundance of Capital. The implication is that the long-term secular decline in interest rates will persist until we find a way to absorb or destroy the capital. We are cursed as old King Midas was, with wealth beyond what previous generations could only dream of and more. There is so much capital that if all you want is a passive “risk-free” return you increasingly are penalized for that–isn’t that the meaning of $13 trillion of negative yielding bonds?

The Swiss 30-year yield has been negative since the start of the month, and now some are asking whether the 30-year German Bund, currently yielding a little less than 30 bp can join it in negative territory. The yield of the US 10-year note has been trending lower since 1981 through business cycles and a range of monetary policy frameworks and content. The surplus capital challenge is secular, not cyclical.

Lower interest rates mean that investors should lower expectations for future returns. There is another implication. The internal hurdle rate for investments by corporations also needs to be reduced. The failure to do so leads to under-investment and more cash, which is paying a diminishing return.

Just like the idea of carbon traps is to taking this poisonous gas out of the air, what is popularly called financialization was an attempt to create a place that could absorb the vast amounts capital that was being built, which industry did need so much. What the Great Financial Crisis did was to illustrate the limitations or challenges in managing the consequences. Said differently, an important takeaway from the GFC was that the financialization process can lead to instability that has a feedback loop into the real economy.

China is part of the story too, and also a part that we seem to lose track of the underlying strategy. From a political economy point of view, the real threat from China does not come from the places that seem to capture people’s attention, like bad loans and ghost cities. These are issues for China, but the global challenge arises from China’s huge capacity. The strategy was to integrate China into the world economy with things like the WTO ascension to help manage this process. Like Brexit, the absorption of China’s vast scale can happen orderly or disorderly, and the risks of a disruptive outcome appear to have increased. Either way, the thrust is deflationary, aggravating those forces that are pushing down the cost of capital in the high-income countries.

News that US and Chinese negotiators are talking again ahead of Trump and Xi’s meeting next weekend was greeted with a spurt optimism and equity buying. The combination of the monetary signals and the trade talks lifted the Shanghai Composite nearly 4.5% last week to two-month highs, while the S&P 500 was up half as much but closed at new record highs. Apparently, The US Administration thinks that a speech by the Vice President criticizing China’s human right practices is too provocative before the trade talks, so it has been delayed again, but blacklisting five more tech companies that are involved with China’s super-computer efforts, is acceptable and was announced before the weekend.

The declaratory position of each side suggests little scope for an agreement. China insists on unilateral disarmament–the US must rescind all of its tariffs that have been imposed. The US demands a concession from China for past wrongs, and that fundamentally alter its economic development model. Comments by President Trump have fanned Chinese fears that America’s real goal is to contain it. China’s flaunting of international trade norms is disruptive and perceived as aggressive acts.

The most that can reasonably be hoped for from the Trump-Xi meeting is another cease-fire in the trade war. Trump would suspend the 25% tariff on the remaining $325 bln or so of Chinese imports that could go into effect as early as next month. Trade talks would resume, perhaps for some fixed period. A trade agreement will be hard enough to strike, let alone a Grand Bargain. Despite the implications of Chinese demographics, Chinese officials see time on their side. It has not peaked, while many see the US as in an inexorable decline.

Tags: Featured,Interest rates,newsletter,Surplus Capital,Trade