Why do humans tend to behave in herds? It’s a fundamental question that only recently have researchers been able to better understand. On the one hand, it doesn’t take an advanced degree in some neurological science to see the basis behind it; survival for our ancestors often meant getting along with the crowd. There are times when that very trait applies still. In 2009, neurologists in the UK conducted function magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans on volunteers. The subjects were asked to rate the attractiveness of faces while being swayed by what they were told were the group’s overall assessments. What scientists found on those scans was that when one person’s rating conflicted with the group’s view that

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: China, China Fixed Asset Investment, China Industrial Production, China Retail Sales, currencies, economy, fai, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, fixed asset investment, Global Growth, globally synchronized growth, industrial production, Markets, newsletter, Retail sales, there is no boom

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Why do humans tend to behave in herds? It’s a fundamental question that only recently have researchers been able to better understand. On the one hand, it doesn’t take an advanced degree in some neurological science to see the basis behind it; survival for our ancestors often meant getting along with the crowd. There are times when that very trait applies still.

In 2009, neurologists in the UK conducted function magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans on volunteers. The subjects were asked to rate the attractiveness of faces while being swayed by what they were told were the group’s overall assessments. What scientists found on those scans was that when one person’s rating conflicted with the group’s view that person’s brain gave off what was characterized as a “prediction error-like response.”

In other words, researchers believe that our brains rewire or retool themselves when our own opinions or beliefs fall outside those perceived of the group. It can help explain cults, Nazis, and maybe even Economists.

In the public opinion regarding the economy, what counts as the “norm” is harder to see and appreciate. We can’t observe the economy directly, so our views on it are shaped by a variety of outside factors. Figuring what everyone else thinks is left often to what “experts” believe. This top-down method becomes, I think, quite easily the case where everyone tends to think what those at the top do, especially when it is repeated so often.

For my work, that’s about the only way I can begin to explain the current economic boom. I don’t mean that this particular psychological study unleashed a torrent of similar ones, so much that there has been a burst of medical equipment spending sufficient to bring the global economy right out of its decade-long funk.

What I do mean is much simpler. “They” keep calling this a boom, and it is often characterized in the mainstream as a big one – the biggest, some people are saying, since 2007 (which isn’t really a sufficient standard to begin with, but that’s for another day). Economists are constantly characterizing the economy as great, therefore the norm has become the economy is great, leaving our brains to believe it has to be because that’s what everyone else thinks.

And I keep asking where?

Central to this boom thesis is China, in no small part because China is and has been central to the global economy. If “globally synchronized growth” is anything other than a projected slogan, we should see it inarguably in China’s numbers. What we find instead isn’t booming, but its opposite. Because that kind of interpretation is so far now from the norm, maybe that’s why even people who pay attention to Chinese econ stats don’t appear to think they are all that bad.

We can start with imports for December 2017. As noted last week, imports year-over-year gained just 4.5% last month. That was not just a weak figure but an alarmingly bad one, requiring, of course, corroboration in the form of additional weak months for imports or some other sector of China’s economy estimated to be in a similar state. We know, as I wrote last Friday, exactly what sector that would be and right where to look:

How much China imports sets the agenda for the rest of the global economy beneath it on the supply chain. Which potentially means: no acceleration in top level global growth (despite it being, purportedly, synchronized for the first time since 2007), lower Chinese exports, less manufacturing growth, reduced need for additional ghost cities, lower FAI as fewer will be constructed, leaving less of a need to import material.

| The link in the economic chain immediately before imports is Fixed Asset Investment. FAI drives everything in China, and is driven by Chinese perceptions of the global economy. It is for China’s internal economy what China’s economy is for the worldwide system.

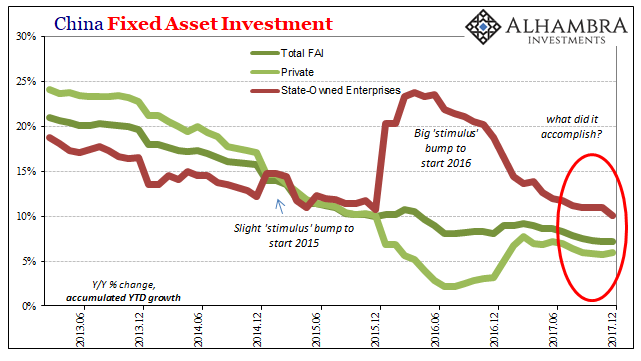

The way in which Chinese officials calculate and present FAI is a bit peculiar. They have their reasons (which are immaterial to this discussion) which in the past justified producing estimates for FAI on an accumulated basis. That means that for December 2017, the National Bureau of Statistics estimates what FAI was in all months of 2017 up to and including the last one. Accumulated FAI last year was RMB 63,168 billion, up from RMB 59,650 billion accumulated throughout 2016. That’s an increase of 5.9%, which is not good (and it isn’t the same as what the NBS press release claims). In terms of just Private FAI, on an accumulated basis it was up 4.5%, which is not good. State-Owned FAI, that had been the basis for growth at least in the first half of last year, was up by its end an accumulated 9.3%, which, given everything else, is not good. |

China Fixed Asset Investment, June 2013 - Dec 2017(see more posts on China Fixed Asset Investment, ) |

| But all that accumulating has the effect of obscuring more recent changes, growth rates in single months later in the year become more and more entangled in the full year basis. Since 2017 started relatively more positive, that ends up coloring the rest of the estimates for last year (which was often the point).

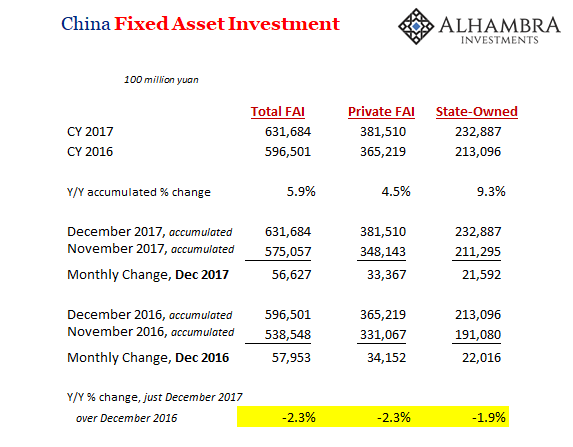

Fortunately, it requires very little effort to produce monthly figures. When doing so, however, suddenly December’s conspicuously weak import number appears all-too-consistent. |

China Fixed Asset Investment, Dec 2016 - 2017(see more posts on China Fixed Asset Investment, ) |

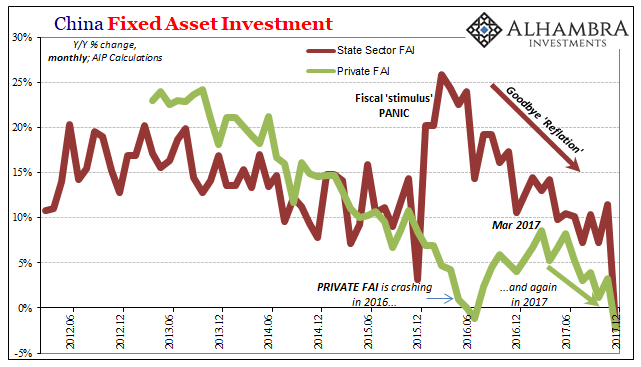

| Here it is in more startling and dramatic graphical form: |

China Fixed Asset Investment, June 2012 - Dec 2017(see more posts on China Fixed Asset Investment, ) |

| Where do we even begin here? I’ll start with the State-owned portion. It seems to further confirm the idea emanating from the 19th Party Congress, the one where China has accepted a no-growth world and is no longer interested in stretching its finances via fiscal “stimulus” that does it and everyone around it no good. You can, I hope, further understand why they appear to have put all the eggs in the Hong Kong basket. Stable CNY, and however far they might manage to de-dollarize along the way, may be all that’s left for them. |

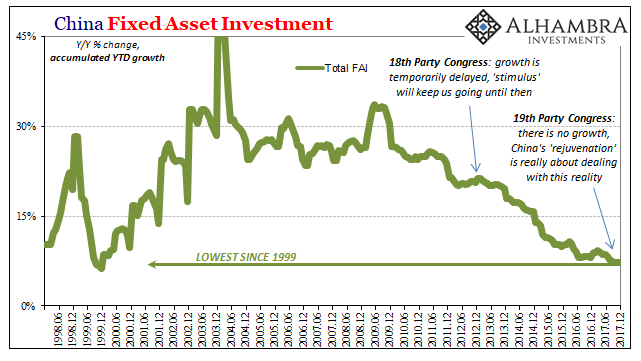

China Fixed Asset Investment, Jun 1998 - 2017(see more posts on China Fixed Asset Investment, ) |

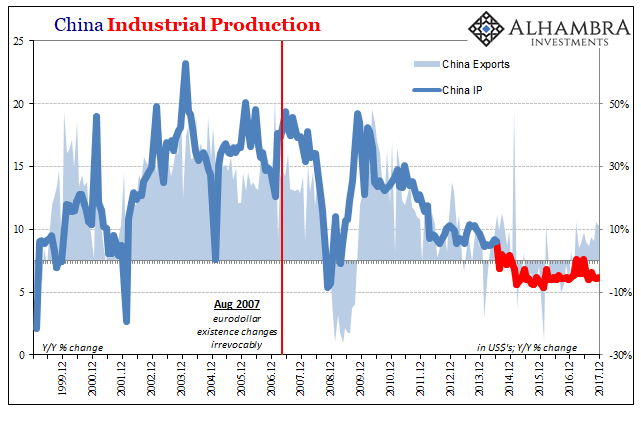

| If Chinese officials are throwing in the towel, why would private entities do anything different? The other two of China’s Big 3 economic stats (GDP doesn’t count for anything besides pure, adulterated propaganda) continue to confirm the utter lack of growth within and more so without. Industrial Production was again growing at just more than 6% in December, which actually calls further into question its veracity (what are the chances IP, or any economic estimate, can remain pretty steady at and near 6% for going on three years?). |

China Industrial Production, Dec 1999 - 2017(see more posts on China Industrial Production, ) |

| And since there are all sorts of questions about China’s GDP, we can reasonably assume that 6% for IP if it is similarly “massaged” is something like a ceiling; if it came out better in the raw data, they would have no reason to reduce it.

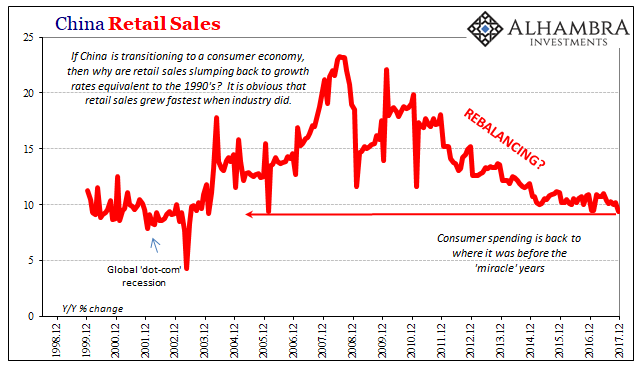

At the same time, retail sales growth was the lowest since a single monthly aberration in 2006, and really the worst since China’s economy accelerated into its “miracle” years fifteen years ago. |

China Retail Sales, De 1998 - 2017(see more posts on China Retail Sales, ) |

Therefore, if China’s economy is still persisting with downside rather than upside bias and risks, and at the same time Chinese officials have thrown up their hands about changing this, why wouldn’t private companies begin cutting back on capex and production? A seriously lower growth baseline like that, however, isn’t what everyone keeps talking about.

It is not a boom. It is, in fact, the very reverse of one. This about a whole lot more than China. The only way it makes sense that the media continues to pound this growth story is that nobody wants to challenge what has become the unverified but accepted norm. Who’s going to argue China FAI with the Ivy League statistician?

What a way to start 2018. What an unbelievably dishonest state of affairs. Globally synchronized growth.

Tags: China,China Fixed Asset Investment,China Industrial Production,China Retail Sales,currencies,economy,fai,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,fixed asset investment,global growth,globally synchronized growth,industrial production,Markets,newsletter,Retail sales,there is no boom