In recent months, Ray Dalio seems to be undergoing a deep midlife and identity crisis, which has not only led to dramatic recent management changes at the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater, but also resulted in some fairly spectacular cognitive dissonance, as Dalio first praised, then slammed, president Trump. Yesterday. in the latest expression of his building anti-Trumpian sentiment, Bridgewater released a 61-page report looking at “Populism: the Phenomenon“, which describes what Bridgewater sees as the “archetypical populist template,” which the fund built out through studying 14 past populist leaders in 10 different countries. The unspoken message in the report is that the US is the 15 example of the “populist leader”, and since all 14 cases presented by Dalio had less than happy endings, the implication is that Bridgewater is hardly optimistic or excited about the near-term future for the US. Dalio’s politics aside, however, the report, among other notable historical observations, has a fascinating aside into what happened some 100 years ago in post-World War I and Tsarist Russia under Vladiir Lenin and the Russian Revolution.

Topics:

Tyler Durden considers the following as important: Bolshevik Party, Bolsheviks, Bridgewater, Capital Markets, Cognitive Dissonance, Councils, default, Eastern Front, Economic history, Featured, February Revolution, German army, Germany, Hyperinflation, Nassim Taleb, Nationalization, newsletter, October Revolution, Political parties in Russia, Politics, PrISM, Ray Dalio, Red Army, Russia’s military, Russian Civil War, Russian Revolution, Socialism, Socialist Party, Socialist Revolutionary Party, Soviet Union, Switzerland, Turkey, Vladimir Lenin, War

This could be interesting, too:

Investec writes The Swiss houses that must be demolished

Claudio Grass writes The Case Against Fordism

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

In recent months, Ray Dalio seems to be undergoing a deep midlife and identity crisis, which has not only led to dramatic recent management changes at the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater, but also resulted in some fairly spectacular cognitive dissonance, as Dalio first praised, then slammed, president Trump. Yesterday. in the latest expression of his building anti-Trumpian sentiment, Bridgewater released a 61-page report looking at “Populism: the Phenomenon“, which describes what Bridgewater sees as the “archetypical populist template,” which the fund built out through studying 14 past populist leaders in 10 different countries.

The unspoken message in the report is that the US is the 15 example of the “populist leader”, and since all 14 cases presented by Dalio had less than happy endings, the implication is that Bridgewater is hardly optimistic or excited about the near-term future for the US.

Dalio’s politics aside, however, the report, among other notable historical observations, has a fascinating aside into what happened some 100 years ago in post-World War I and Tsarist Russia under Vladiir Lenin and the Russian Revolution.

Here are the key highlights;

World War I proved to be Tsarist Russia’s death knell: Russia’s military suffered severe defeats against Germany, leading to massive casualties, as well as high inflation and food shortages. In response, an initial revolution occurred in early 1917 (the February Revolution), forcing the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and producing a liberal republic that legalized political parties.

It was during Russia’s short-lived and weak democratic period that Vladimir Lenin and the Bolshevik Party were able to seize power. The new provisional liberal government, formed by members of the prior legislative assembly, was barely more effective than the earlier regime. It was forced to share power with the councils of workers (the “Soviets”) that helped organize the revolution and had more support from workers and soldiers. The provisional government became unpopular when it unsuccessfully continued Russian participation in WWI. With political parties no longer barred, Lenin decided to return from his exile in neutral Switzerland (with the help of the German army, which hoped to create further disorder in Russia). Lenin helped lead the Bolshevik Party to prominence, and in the October Revolution of 1917, he led a second (initially largely bloodless) revolution against the new Russian republic, seizing power. Hoping to give the revolution democratic legitimacy, the Bolsheviks still held a previously planned election in November—which they lost to a different socialist party (the Socialist Revolutionaries) that was broadly supported by the rural poor. But Lenin was able to take advantage of Russia’s weak democratic institutions, no rule of law, and disunity among the Socialist Revolutionaries to void the election and maintain control. Almost immediately, anti-communist forces rebelled against Bolshevik rule, sparking a brutal, multi-sided civil war that resulted in the victory of the more united and better organized Red Army, and the creation of the USSR in 1922.

Lenin aimed to create an economy where the means of production were state-owned and centrally planned. As a central Bolshevik policy, abolishing private property was one of Lenin’s first moves. Following the Russian revolution, the Decree on Land in October 1917 abolished private property and seized the estates of wealthy Russians with no compensation, giving the land to the state and allowing peasants to continue to farm. Lenin also launched a campaign to seize the personal wealth of the aristocracy and return it to the government, rallying mobs to prevent the wealthy from escaping the country:

The bourgeoisie are concealing in their coffers the riches which they have plundered, and are saying, ‘We shall sit tight for a while.’ We must catch the plunderers and compel them to return the spoils.

This was followed by the compulsory nationalization of Russian industry. Nationalizations started at the company level, with workers, empowered by Lenin’s decrees, replacing the factory owner with newly formed committees to run the business. Later on this process became more centralized, as entire sectors were nationalized at once as the Bolsheviks installed commissioners to oversee major corporations or industries. By mid-1918, the Bolsheviks had nationalized most factories, mines, and farms, and the government was strictly regulating production and prices—ordering workers to produce, then seizing and reissuing the output.

* * *

Lenin’s nationalization of the banks appeared to precipitate an economic crisis. In late 1917, Lenin seized all deposits of the aristocracy and corporations, sparing only the small savings accounts of workers, effectively creating capital controls on the aristocracy’s ability to get wealth out of Russia. In addition, Lenin’s policies criminalizing capitalism expanded through 1918 to outlaw interest payments and he defaulted on all government debt (worth over $600 billion in today’s dollars), wiping out most of the wealth that investors had left in Russia.

Liquidity seized up in response. A strike by bank workers in response to nationalization, starting in December 1917 and going for months, effectively shut down the banking system, meaning many newly nationalized businesses that relied on banks couldn’t pay their workers. The government responded to the crunch by printing money to fund the newly nationalized industries. Still, many factory committees, in search of someone to blame for late wages, fired managers and other senior employees, making it difficult to function and meet the decreed production quotas. At the same time, foreign governments retaliated against the Russian default by freezing Russia’s foreign assets. As controls escalated, many Russians tried to move what remained of their wealth, and often themselves, out of the country, reinforcing the squeeze. From 1917 to 1920, between 1 and 2 million Russians left the country and settled across the globe.

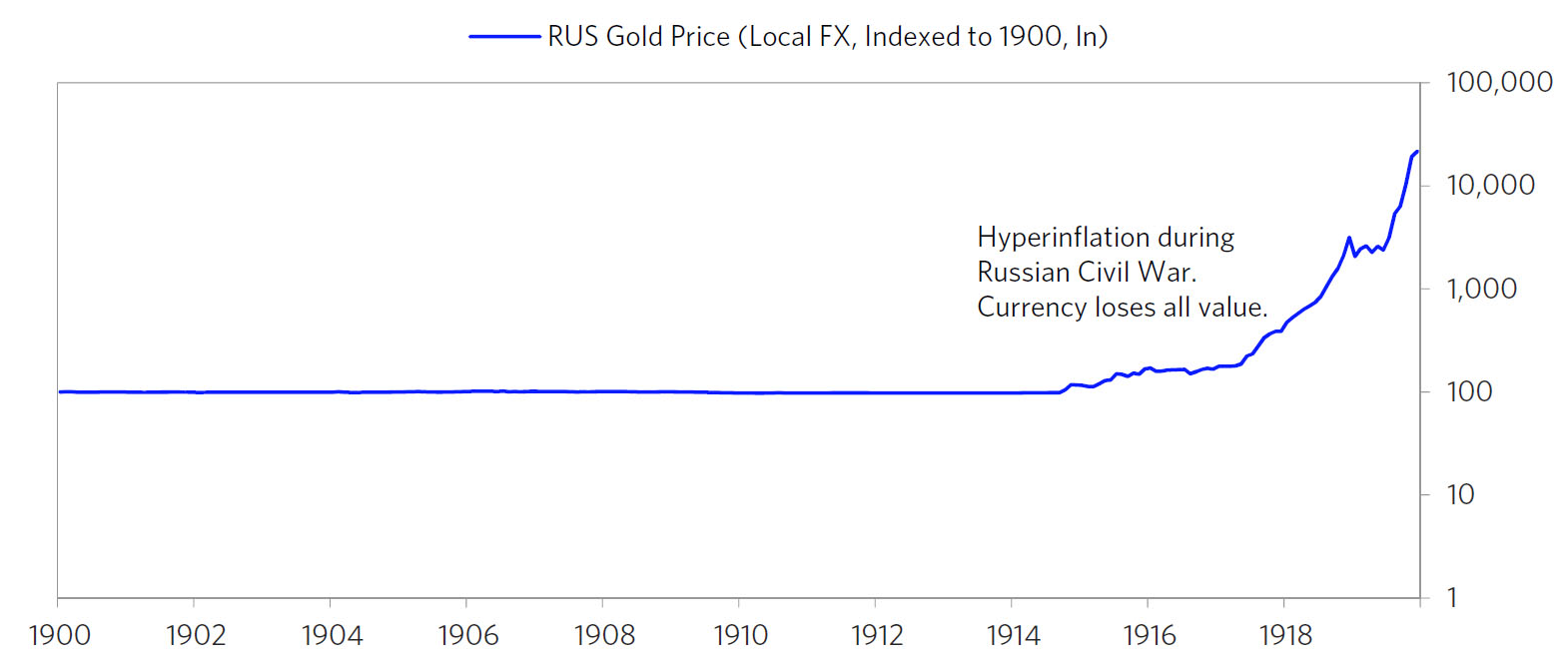

The resulting economic collapse—caused by the combination of asset confiscation, civil war, and a banking crisis—was devastating. As capital pulled out, the ruble collapsed, and the economy spiraled into hyperinflation.

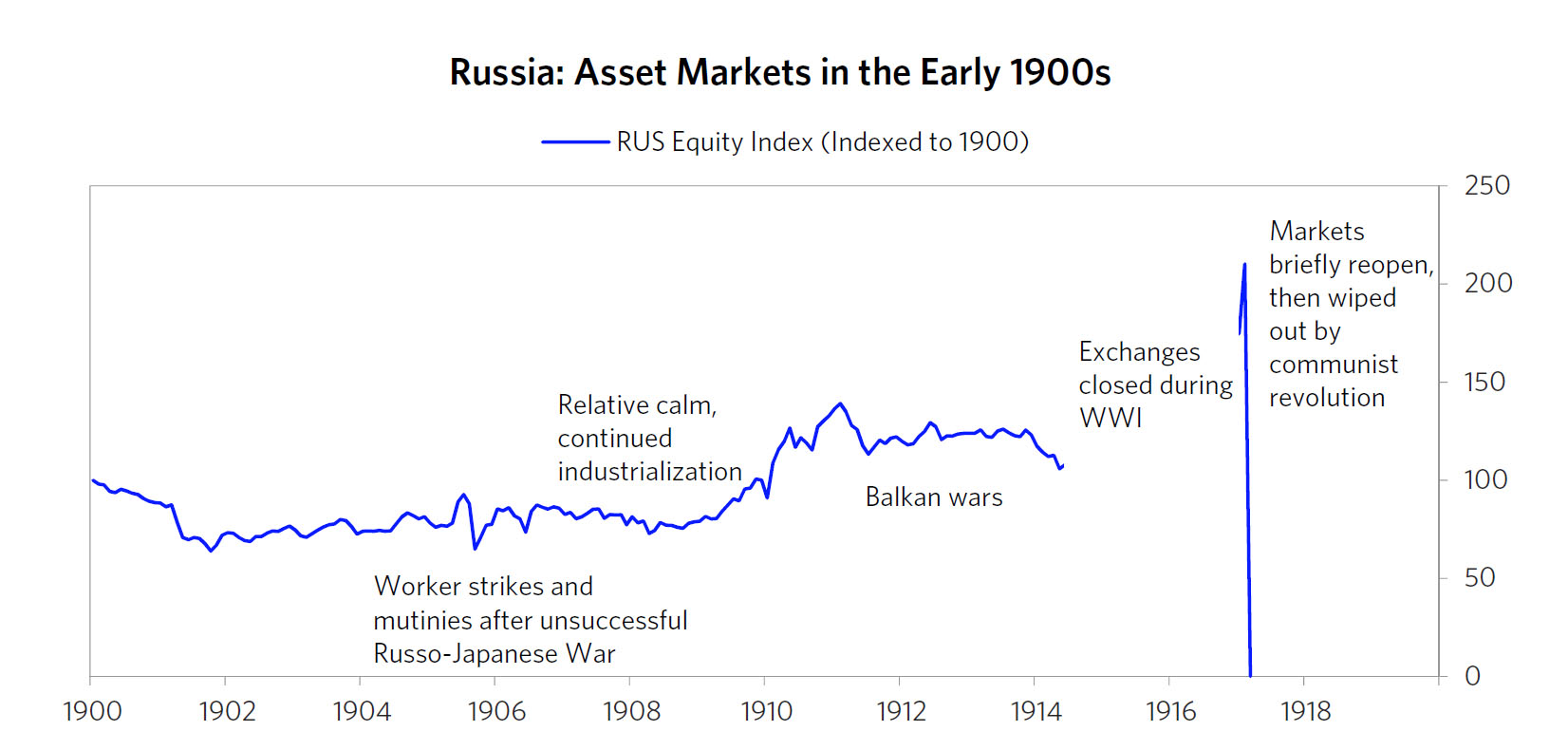

| How did all of the above look like through the prism of capital markets? Actually, very much like something out a Nassim Taleb book, specifically when looked at from the perspective of the Turkey, because while stocks were shut down during World War I, they nearly doubled upon reopening after the fall of the Tsarist regime, however not for long… Because just a few days later, Russian stocks had a very bad day, and once Lenin nationalized everything and abolished private property, Russian equities lost all their value overnight. | |

| Ironically, “Turkey” investors were just as delighted with not only the early days of the post-tsarist regime in Russia, but also of Hitler Germany. where the stock market nearly tripled between Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor in January 1933, and March 1938 when Germany annexed Austria.

As for the only asset that survived the disintegration of the Russian economy one century ago, it is shown in the chart below. It would be ironic, and painfully amusing, if the US – as Dalio is implying tongue-in-cheek – and its stock market, ends up as Russia circa 1917. |

Russia Gold Price 1900 - 1918 |