Authored by Peter Cleppe, originally posted at Euro Insight, If Brexit marks the beginning of the end for the European project, Brussels will take its share of the blame If Britain leaves the EU and if the reaction to Brexit causes years of uncertainty, the EU will reap what it has sowed. British discontent is only a precursor to unrest on the Continent, where populists from across the political spectrum feel they have lost control over their fate, and are gaining popularity. We’ve seen the transfers of power to the European level after ignoring the referendums on the European Constitution in France and the Netherlands in 2004. We’ve witnessed the refusal to allow Grexit, which could have been an alternative for continued fiscal transfers and interventions into national budgetary decisions. Both have created a lot of discontent and anti-EU sentiment since 2010. Last year, there was the decision to outvote Central and Eastern Europe on the sensitive issue of forcing countries to accept refugees, which isn’t even possible in a passport-free zone, as people can travel freely, but which was decided to divert attention from criticism on Angela Merkel’s controversial refugee policy and to organize yet another transfer of power to the EU level.

Topics:

Peter Cleppe considers the following as important: Credit Suisse, David Cameron, Eastern Europe, Featured, France, Germany, Netherlands, newsletter, Norway, Switzerland

This could be interesting, too:

investrends.ch writes UBS zahlt für CS-Steuerstreit mit US-Justizministerium weitere halbe Milliarde

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Authored by Peter Cleppe, originally posted at Euro Insight,

If Brexit marks the beginning of the end for the European project, Brussels will take its share of the blame

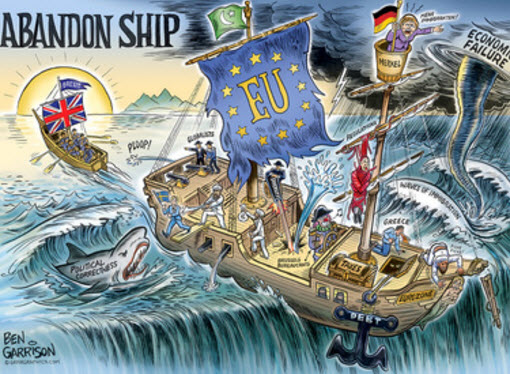

If Britain leaves the EU and if the reaction to Brexit causes years of uncertainty, the EU will reap what it has sowed. British discontent is only a precursor to unrest on the Continent, where populists from across the political spectrum feel they have lost control over their fate, and are gaining popularity.

We’ve seen the transfers of power to the European level after ignoring the referendums on the European Constitution in France and the Netherlands in 2004. We’ve witnessed the refusal to allow Grexit, which could have been an alternative for continued fiscal transfers and interventions into national budgetary decisions. Both have created a lot of discontent and anti-EU sentiment since 2010.

Last year, there was the decision to outvote Central and Eastern Europe on the sensitive issue of forcing countries to accept refugees, which isn’t even possible in a passport-free zone, as people can travel freely, but which was decided to divert attention from criticism on Angela Merkel’s controversial refugee policy and to organize yet another transfer of power to the EU level.

Finally, we could see how Prime Minister David Cameron’s proposals to bridge the gap between the EU and citizens were met with a lukewarm reaction. His proposal, for example, to allow national parliaments to block EU proposals was watered down to make it harder to implement.

If the British vote to ‘Remain’, they most likely won’t do so with a majority of more than 60%. That however is the threshold needed, according to pollster Comres, to really settle the debate for the next few years.

With a narrow victory for the ‘Remain’ camp, it is therefore more than likely that the debate would just start over the next day, very much like the Scottish demand for independence which has remained a prominent feature in UK politics after 44.7% of Scots voted to secede from the UK in a referendum in 2014.

If people vote to ‘Leave’ the EU, the government is likely to activate article 50 of the EU Treaty, which foresees that the status quo is maintained for two years and that both parties are given the chance to renegotiate their relationship.

Many think that two years will be much too short for this. The British government thinks that there could perhaps be 10 years of uncertainty, while EU Council President Tusk has mentioned seven years. Some in the ‘Leave’ camp have claimed that there may even be a second referendum after a Brexit vote, whereby Britain would get the chance to remain in the EU after all, but under better conditions than those negotiated by Cameron in February this year.

It’s unlikely that the UK would want a relationship similar to that between Norway and the EU. Norway may have complete access to the European single market because of its membership of the European Economic Area but in exchange it needs to comply with over a set of EU rules without having any influence over them within the EU institutions. That surely won’t be an option for a country which just would have left the EU because of a desire to have more sovereignty.

Also, to have the EU-Canada trade deal (CETA) as a model, as advocated by the ‘Leave’ campaign’s Boris Johnson, may not be appealing, given the lack of access the financial services industry would enjoy to the EU market.

The British may prefer something like the Swiss model instead, which means that the UK and the EU would negotiate which markets they would open to each other and which rules they would harmonise or mutually recognize. At the moment, a Swiss firm like Credit Suisse is based in London in order to be able to access the EU’s single market, so some extra hurdles may emerge.

Whatever trade relationships are pursued by a post-Brexit Britain, it’s very possible that a Brexit vote would unleash protectionist sentiment on the Continent and that the EU would want to punish the “naughty pupil” by means of limiting market access for British financial firms. Diplomats have already made clear that both France and the EU Commission are keen to “punish” the UK if it would vote to leave, while Germany, which exports a lot to Britain, is planning to be more conciliatory in the event of a vote for Brexit.

This protectionism would both hurt Britain and the Continent, given that the City of London can be seen as its financial lifeline. It would in any case be similar to the EU’s reaction to Switzerland, after the Swiss expressed in a referendum the desire to restrict free movement for EU citizens and the EU Commission essentially refused to negotiate.

British proponents of EU membership have made the case that Cameron’s deal guarantees that the “high-watermark” of EU intervention in British policy has been reached.

But EU opponents have questioned how legally binding the deal is, leading to obscure debates on the relationship between international and EU law. They have claimed that even after threatening the nuclear option – a referendum on Brexit – Cameron didn’t manage to obtain more than what they consider to be peanuts.

One thing is certain: if Brexit marks the beginning of the end of the EU project, many of those responsible are to be found in Brussels.