In a recent article by Kessler Companies (hat tip Zerohedge) they correctly point out that inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, have a tendency to accelerate as the US economy moves into a recession. Contrary to popular belief, the beginning of a recession is not deflationary but the exact opposite. As can be seen from the chart, consumer prices do indeed move higher into recessions as represented by the shaded areas. Why? The most obvious explanation is simply that the Federal Reserve is forced to act, as the CPI signal (or more accurately the PCE) trigger rate hikes. This increases borrowing costs and disrupts the established money flow forcing the economic system to reallocate resources accordingly. As households home equity lines dries up, there will be less spending on, say, restaurants which concomitantly changes relative prices – wages for waiters fall relative to other wages – and resources then start to flow into other parts of the economy seeking profits where they are easier to achieve. Needless to say this process takes time and is commonly known as a recession. The obvious correlation between effective federal funds rates and the CPI substantiates our claim. The real federal funds rate or the spread between “core” CPI and the federal funds rate brings the point home.

Topics:

Eugen von Böhm Bawerk considers the following as important: Bawerk, Economics, Featured, newsletter, Price Inflation, US

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

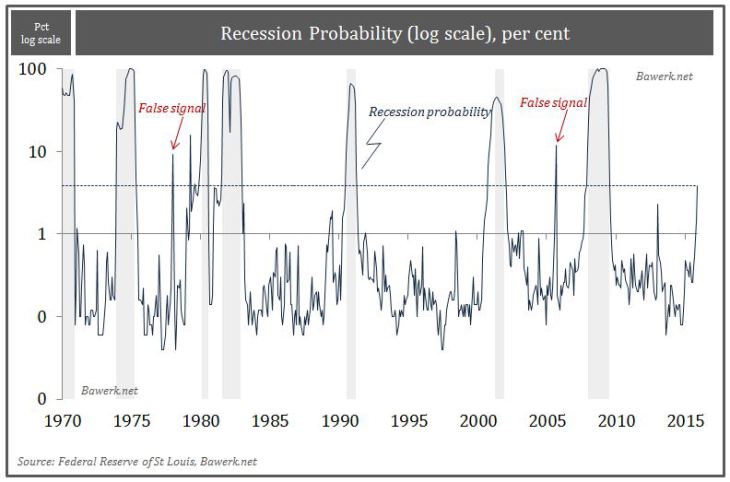

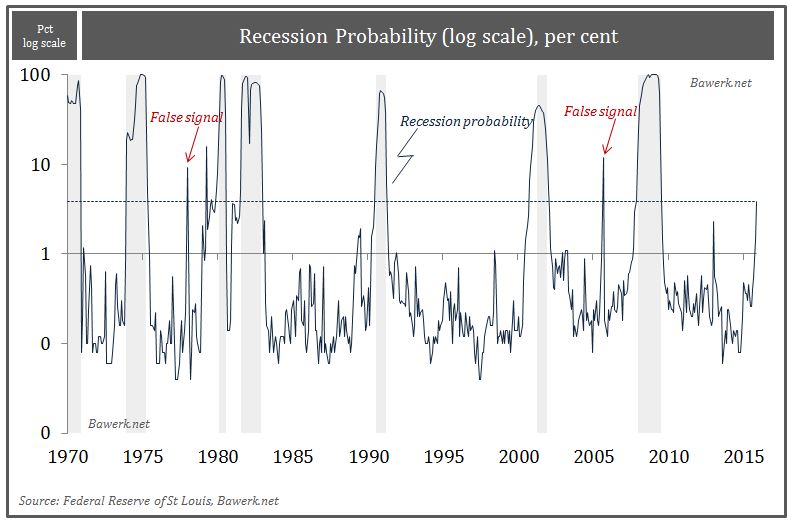

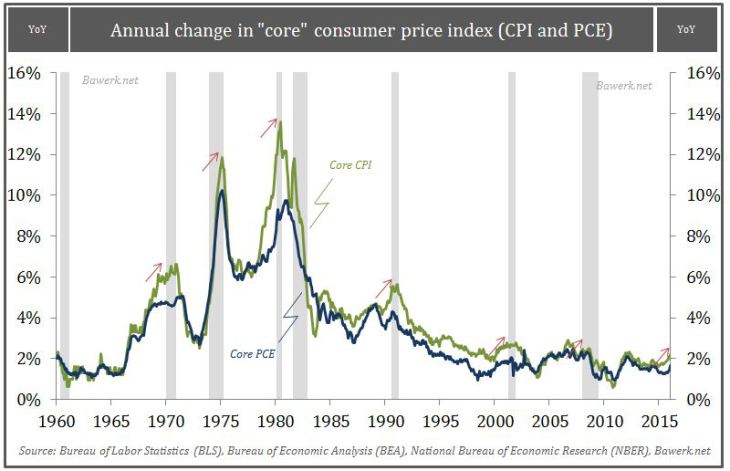

In a recent article by Kessler Companies (hat tip Zerohedge) they correctly point out that inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, have a tendency to accelerate as the US economy moves into a recession. Contrary to popular belief, the beginning of a recession is not deflationary but the exact opposite. As can be seen from the chart, consumer prices do indeed move higher into recessions as represented by the shaded areas.

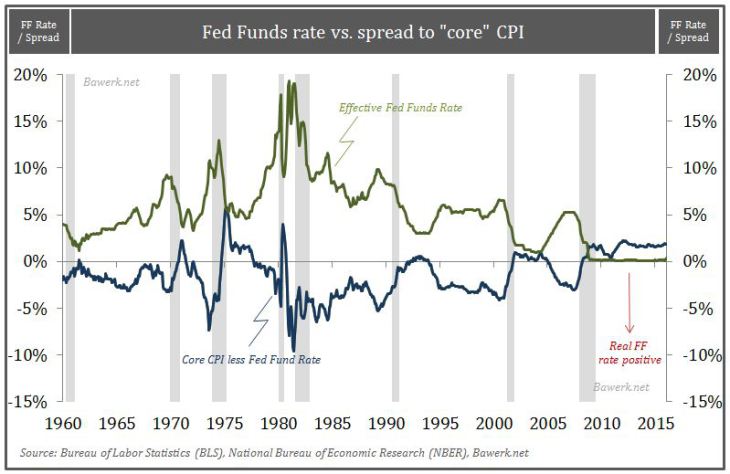

Why? The most obvious explanation is simply that the Federal Reserve is forced to act, as the CPI signal (or more accurately the PCE) trigger rate hikes. This increases borrowing costs and disrupts the established money flow forcing the economic system to reallocate resources accordingly. As households home equity lines dries up, there will be less spending on, say, restaurants which concomitantly changes relative prices – wages for waiters fall relative to other wages – and resources then start to flow into other parts of the economy seeking profits where they are easier to achieve. Needless to say this process takes time and is commonly known as a recession.

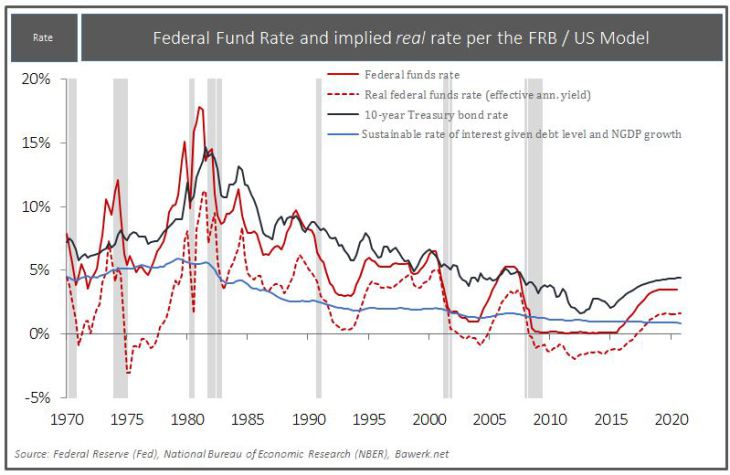

The obvious correlation between effective federal funds rates and the CPI substantiates our claim. The real federal funds rate or the spread between “core” CPI and the federal funds rate brings the point home.

Prior to every recession the real federal funds rate moves higher (more negative in the chart) and then make an abrupt about-turn as the Federal Reserve realize they have moved too far as the process becomes deflationary. It is also highly noteworthy that since the GFC the real federal funds rate have been negative for an unprecedented amount of time. Compare that to the brief period of negative real yields prior to the GFC and what that lead to and you quickly realize how much economic malinvestments and dislocations are present in the system.

If we are going with the current forecast by the Federal Reserve staff the implied real federal funds rate will go from unprecedented negative to strongly positive in short order. It is also highly concerning that the calculated sustainable rate of interest given federal debt levels and assumed nominal GDP growth falls below the expected path of the federal funds rate. In other words, as the Federal Reserve intend to move us away from ZIRP with the rest of the world rushing headlong into NIRP (good luck with that) we are bound to bump against the recession ceiling. It has happened every time they tried it before.

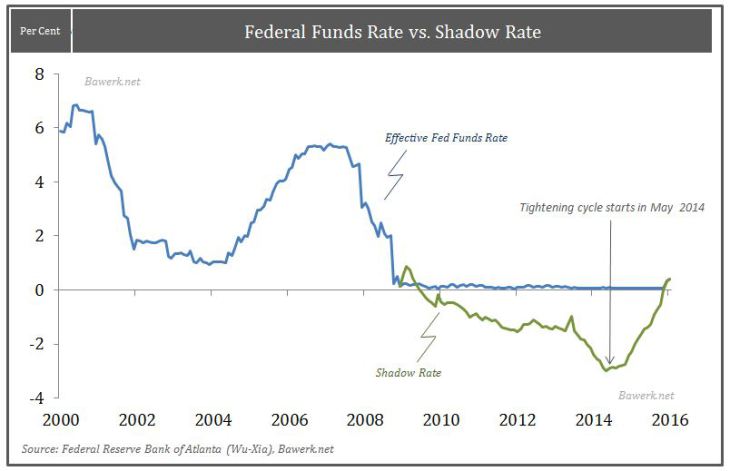

In addition, the tightening cycle is actually far more mature than the tiny hike in December would have you think. Wu and Xia’s “shadow rate” tries to estimate the effect forward guidance and various QE and MEPs have had on financial conditions and from that provide what the actual rate is. By their estimate the tightening cycle started already back in May of 2014

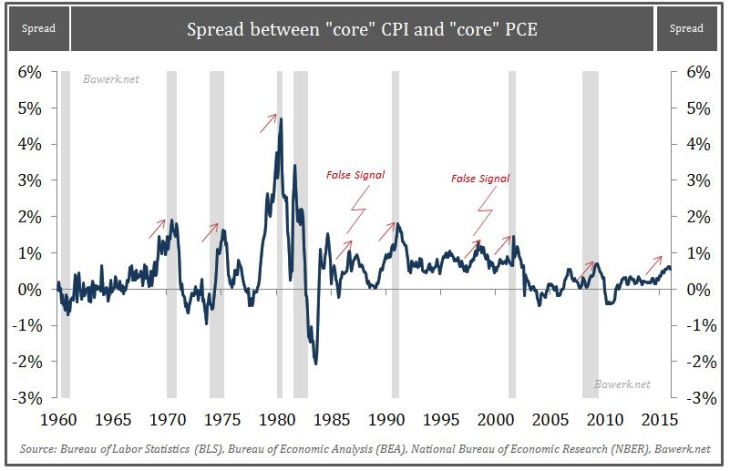

This is all well and good, but what caught our eyes when looking at the Kessler chart recreated above was the increasing spread between “core” CPI and PCE as the economy entered into a recessions. The CPI historically starts to accelerate into a recession while the PCE seems to lag behind. The spread between the two widens into recessions and then comes back down and stabilizes after the recession.

The main difference between the “core” CPI and PCE is the weight allocated to shelter. The CPI is far more sensitive to changes in cost of shelter, as the index allocates over 40 per cent to housing, than what the PCE index is.

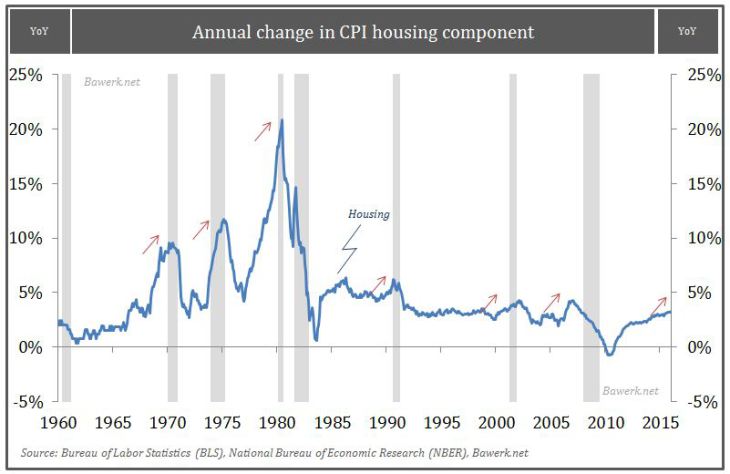

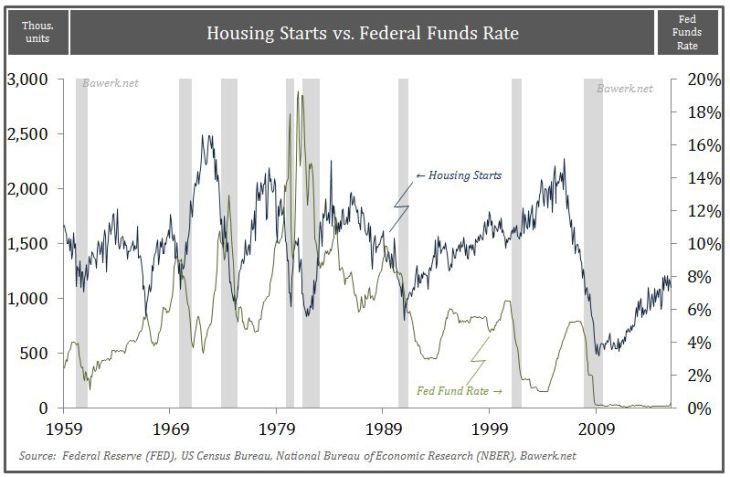

Housing is obviously very interest rate sensitive and thus easier for monetary authorities to manipulate than many other goods that enter into the CPI basket. A look at the housing component reveals the same pattern. Housing costs, either through increased price of houses or higher rent for shelter in general tend to accelerate higher as we move into recessions. With housing cost driving up CPI, the Federal Reserve hike rates and pull the rug under a very interest rate sensitive sector of the economy.

Housing starts drop as higher interest rate reduces affordability and increases debt servicing cost (which put pressure on discretionary spending) and then regain traction as the Federal Reserve start to ease into the recession as household’s affordability improve.

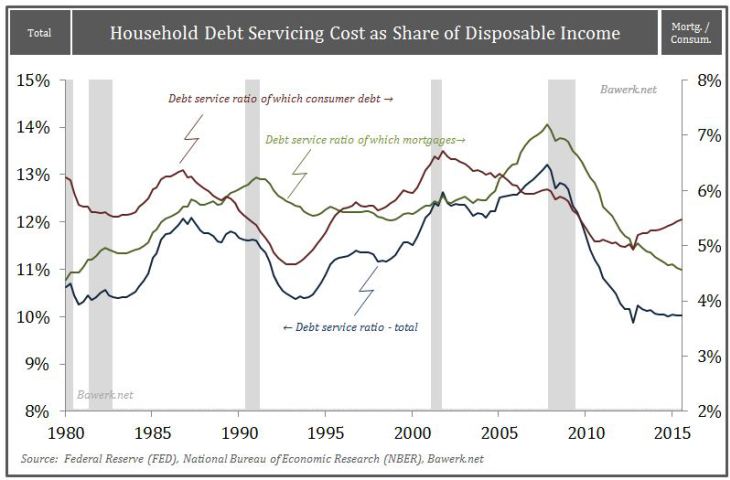

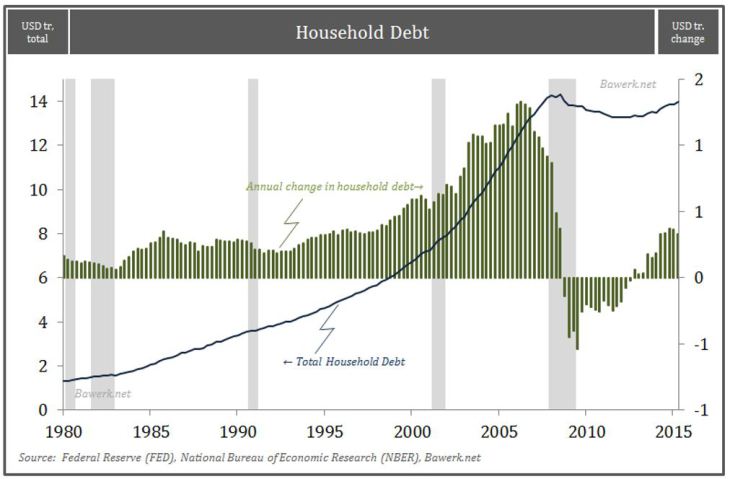

At today’s level US household’s debt servicing cost are at record low levels, while their overall debt is close to record high. This is obviously a function of extremely low rates of interests. However, if, and that is a big if, the Federal Reserve hikes rates, an indebted household sector will rapidly come under pressure, just like the high yield energy space already has.

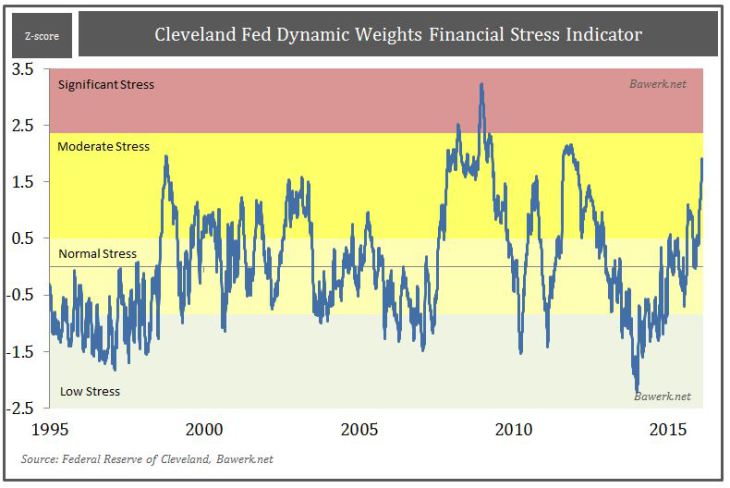

After tightening policy since 2014 with a consequent shift in the US dollar, financial stress is already at very elevated levels and further monetary policy divergence with the rest of the world will only exacerbate this unfortunate development.

Bottom line is simply that the probability of recession is increasing. As we outlined here on several occasions in 2015, we expect a recession by the end of 2016, and if that projection turns out to be wrong due to a massive turnaround in Fed policy, the cataclysmic event will only be postponed till 2017.