If Xi’s gambit succeeds, China could become a magnet for global capital. If success is only partial or temporary, China may well struggle with the structural excesses that are piling up not just in China but in the entire global economy. As noted here last month, the Chinese characters that comprise “crisis” are famously–and incorrectly–translated as “danger” and “opportunity.” The more accurate translation is “precarious” plus “juncture” or “change point.” (Thank you Rick D. for the explanation of juncture.) China is at a critical juncture in history as its foundations of growth–mercantilist exports and property development–have reached diminishing returns. A great deal of what’s written about China starts from an ideological position of pro-China or anti-China.

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

If Xi’s gambit succeeds, China could become a magnet for global capital. If success is only partial or temporary, China may well struggle with the structural excesses that are piling up not just in China but in the entire global economy.

As noted here last month, the Chinese characters that comprise “crisis” are famously–and incorrectly–translated as “danger” and “opportunity.” The more accurate translation is “precarious” plus “juncture” or “change point.” (Thank you Rick D. for the explanation of juncture.) China is at a critical juncture in history as its foundations of growth–mercantilist exports and property development–have reached diminishing returns.

A great deal of what’s written about China starts from an ideological position of pro-China or anti-China. The narrative cherry-picks whatever material supports the pre-selected starting point and then claims a bogus objectivity and authority to mask the bias.

Gordon Long and I take a financial perspective in our video

XI’s GAMBIT: A Bridge Too Far? (41 minutes). Ideology is all well and good but economies are systems that have to actually function in the real world to be sustainable in the long run. All geopolitical ambitions rest on the foundations of the domestic economy and social order. If those falter, geopolitical ambitions crumble into dust.

All economies are dependent on 1) real-world resources, 2) the cost of extracting and transporting those resources, 3) systemic constraints (supply chains, debt service, etc.) and 4) the initial conditions of the system, i.e. the political and financial conditions established at the beginning of the system.

All economies are also impacted by social conditions, for example, the consequences of soaring wealth/income inequality.

China’s extraordinary growth has had four primary engines:

1. Mercantilist exports, i.e. industries designed for exports by mercantilist policies such as China’s currency peg to the U.S. dollar.

2. Property development, in which local governments sell development rights to private-sector developers and developers build millions of apartments (typically in high-rise buildings) that are sold to households.

3. Infrastructure projects such as subway systems, dams, highways, high-speed rail, airports, sports arenas, etc.

4. Debt, which has expanded in all sectors: public, private, corporate and shadow banking / wealth management.

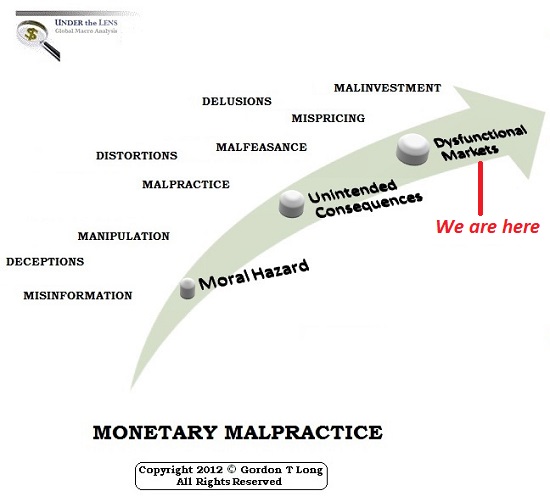

The problem is all four are running into diminishing returns that are veering into malinvestment (i.e. money that could have been better spent elsewhere) and systemic fragility.

As labor and production costs have risen in China, cheaper competitors have emerged, impacting exports. (Charts are included in the video.)

Property development is generating systemic fragility due to the initial conditions established in the early days of opening China’s economy: all land is owned by the central state, but leases (development rights) are sold by local governments.

Property development is generating systemic fragility due to the initial conditions established in the early days of opening China’s economy: all land is owned by the central state, but leases (development rights) are sold by local governments.

The twist that’s unique to China is that these development fees are the primary source of local government revenues, as property taxes are negligible. In other words, if development ceases, local governments lose the primary source of the revenues they need to function.

Property values remain high because demand for investment flats has been favorable. For financial and cultural reasons, real estate is strongly favored as a form of savings and investment. Since inhabited apartments are not as valuable as new or never-inhabited, most investment flats are not rented out; they remain empty.

While upper-middle class families already own two or three empty investment flats, the price (hundreds of thousands of dollars in upper-tier cities) is out of reach for typical workers and rural populations.

In effect, the enormous property development sector is dependent on upper-middle class households buying third, fourth and fifth investment flats as the majority of average workers cannot afford to buy an apartment. For an average worker to buy a flat, the entire family’s wealth must be assembled and huge debts taken on, often in the unregulated shadow banking system.

The marriage prospects of young men who cannot buy a flat diminish greatly, and so there is tremendous pressure on individuals and families to risk their entire store of wealth and mortgage their future to buy a flat.

Most infrastructure has already been built out, so new projects offer only marginal utility. The new airport, train station or mall is mostly empty, the new sports facility is rarely used, and so on. Once high-utility infrastructure has been built, constructing “bridges to nowhere” creates temporary jobs but adds little or nothing to productivity or well-being.

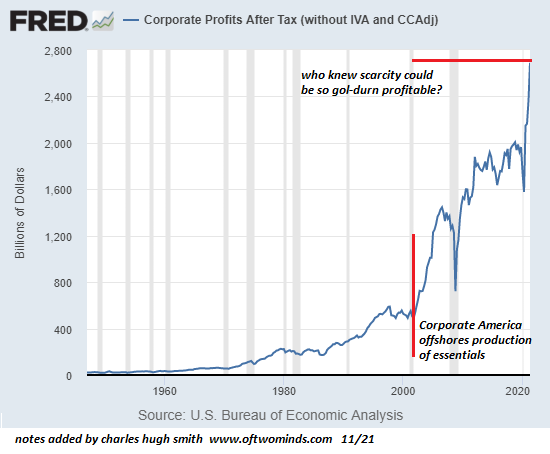

Debt is another dynamic that has positive results early on but eventually becomes a source of systemic fragility if it continues expanding to serve malinvestments and speculation. One word says it all: EverGrande.

Just as in the U.S., politically powerful “too big to fail” players in China have been bailed out by the central government, generating moral hazard: the disconnection of risk and consequence. These central bank/state bailouts of highly leveraged and indebted developers has encouraged players to extremes of leverage, risk and debt that now pose a systemic threat to China’s financial system and public trust.

We’ve seen where malinvestment, moral hazard, declining exports, ballooning debt, dependence on development and “bridges to nowhere” lead: to decades of stagnation and social depression, i.e. present-day Japan, which failed to transition from an export / development dependent economy that worked brilliantly for three decades (1955 to 1985) but then generated a speculative bubble that popped in 1989 with devastating consequences.

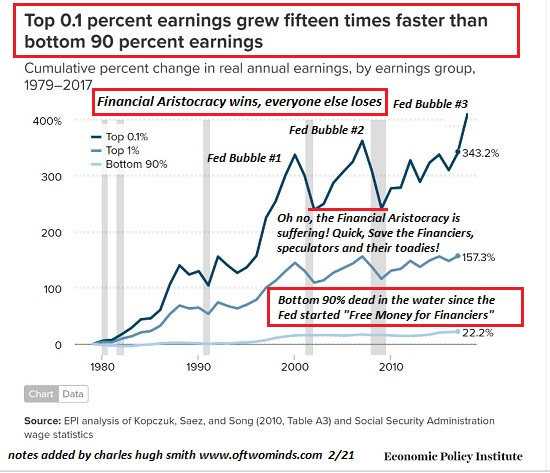

President Xi must foster (or force) a transition to new more sustainable engines of growth, or China will slide down the path to stagnation and speculative bubbles that pop. Xi must also address another source of systemic fragility, soaring wealth inequality, which diverts the lion’s share of income and wealth to a thin slice of the super-wealthy while the purchasing power of workers’ wages stagnates.

If the purchasing power of wages stagnates, you can kiss your consumer-based economy good-bye. Yes, skyrocketing debt can generate a brief spurt of demand, but this is not sustainable or productive. Wages rise from prudent investments that raise productivity of the labor force and economy, not from building empty flats (China) or speculating in meme stocks (U.S.).

The irony of the rivalry between China and the U.S. is both share the same problems: dependence on systems that no longer improve productivity, soaring wealth inequality, massive malinvestment, skyrocketing systemic fragility, rising costs, unprecedented speculative bubbles and a sclerotic, self-serving parasitic elite that resists much-needed reforms.

President Xi has an opportunity to address these systemic challenges. Whether he will succeed or not is unknown; for example, his proposal to institute a property tax–a wise policy transition–immediately encountered enormous resistance from the status quo of private developers and local government officials.

Gordon Long and I discuss Xi’s challenges and opportunities in this precarious juncture in history. If Xi’s gambit succeeds, China could become a magnet for global capital. If success is only partial or temporary, China may well struggle with the structural excesses that are piling up not just in China but in the entire global economy.

Tags: Featured,newsletter