The Baby Boom generation may be the first generation to leave less to their children than they inherited. Or to leave nothing at all. We hear lots—often from Baby Boomers—about the propensities of their children’s generation. The millennials don’t have good jobs, don’t save, don’t buy houses in the same proportions as their parents, etc. We have no doubt that attitudes have changed. That the millennials’ financial decision-making process is different. And that millennials don’t see things like their parents (if you’ve ever seen pictures of Woodstock, you may think that’s not a bad thing). However, we believe that the monetary system plays a role in savings and employment. And the elephant that is trumpeting in the

Topics:

Keith Weiner considers the following as important: 6) Gold and Austrian Economics, 6a) Gold & Bitcoin, Basic Reports, capital consumption, dollar price, falling interest, Featured, gold basis, Gold co-basis, gold price, gold silver ratio, newsletter, purchasing power, silver basis, Silver co-basis, silver price, yield purchasing power

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The Baby Boom generation may be the first generation to leave less to their children than they inherited. Or to leave nothing at all. We hear lots—often from Baby Boomers—about the propensities of their children’s generation. The millennials don’t have good jobs, don’t save, don’t buy houses in the same proportions as their parents, etc.

We have no doubt that attitudes have changed. That the millennials’ financial decision-making process is different. And that millennials don’t see things like their parents (if you’ve ever seen pictures of Woodstock, you may think that’s not a bad thing). However, we believe that the monetary system plays a role in savings and employment. And the elephant that is trumpeting in the monetary room is: the falling interest rate. Interest has been falling since 1981. That’s when the first millennial was born.

By the time the oldest millennial cohort was ready to enter the work force, the dot-com boom was blowing up. What a time to look for a job, eh? Seven years later—when more than half of millennials were still not old enough to work full-time—was an even bigger bust. And what have we had since then? Seven years of interest rates pinned at zero (on the short end of the curve). And then a tepid rise since then.

The yields of all assets are tied to the Treasury bond yield by a process of arbitrage. As goes the yield on Treasurys, so goes the yield on other bonds, bank deposits, stocks, and real estate.

As an aside, even the dollar yield on gold, known as the gold forward rate. People sometimes mistake the gold forward as a yield on gold. But look at the mechanics. You buy gold (with dollars) and sell it forward (for dollars) pocketing a spread (in dollars). It happens to use the gold market, but it’s a dollar return on dollars.

Anyways, the yield of every asset falls with the yield on Treasury bonds. And the asset price is the inverse of its yield. So to those who already own assets, this seems wonderful. What homeowner could object to seeing home values double and then double again? What shareholder could be angry at a ten-bagger?

Somewhere, Emperor Palpatine is chuckling with a dry, mirthless laugh. “Good.”

Monetary policy is working its dark magic. People see the falling yield as rising asset prices. They don’t see the life being sucked from the economic carcass. Instead they see themselves getting rich. At least homeowners. And shareholders.

But what about millennials? They see saving, if not as a Sisyphean task, then at least as a daunting one like counting grains of sand on the beach. And as fruitful. Not only do they get no interest on their bank deposits (we won’t even get into devaluation of the dollar), but the interest rate has done something else to them as well.

People not counted in the workforce hit and remained at record highs. It’s currently about 96 million people in the US. That’s bad enough, at nearly a third of the population. Worse, while workforce participation rates increased for older workers, it decreased for younger people. That is, while almost twice the percentage of workers over 65 have jobs now compared to 1996, a smaller percentage of young workers have jobs.

And those who do have jobs, are under pressure. You see, to their employers, a job is like a perpetuity. It is a stream of payments out indefinitely into the future. The net present value of a perpetuity doubles with every halving of the interest rate. So after the great financial crisis, the burden of employing someone became very high indeed. And employers in turn pass the pressure through to employees. With every halving of the interest rate, the marginal productivity of labor doubles. That is, a worker must produce twice as much or else slip under the margin and be laid off.

This is a picture of having to work harder, just to stay even.

Meanwhile, every kind of tax and fee, audit and compliance, zoning and licensure, lawsuit and regulatory action, regulation and arbitrary rules bear down on businesses. Business profit margins come further under pressure from these non-monetary factors. This leaves them less to pay workers. And they try to pass their rising costs through to consumers (which is what workers are, when they are not on the job).

Is it any wonder that millennials struggle to set aside even a small part of their paychecks? And at zero interest, even if they do, it does not compound.

What’s that? They should buy a house you say? Saving enough for the down payment may be as far away as the moon, for many of these people.

Oh, you said buy stocks? Is that really prudent for someone with only a few months’ cash buffer against a rainy day? Sorry, we misheard, didn’t realize you said they shouldn’t have borrowed so much to attend university. Well, we won’t address those who made the mistake of majoring in a subject for which there is no employment demand. Instead, let’s assume that our hapless millennial majored in something that will help him land a good job.

A degree that increases one’s earnings is an asset. The value of all assets goes up, when interest rates fall. This means people are willing to pay more to get a degree. Should be willing to pay more. Because it’s worth more. And they can borrow more cheaply to get that greater amount of cash to pay for that degree.

You get the picture. Falling interest screws the young people, who are just starting out. Now let’s turn our crosshairs on to their parents, the Baby Boomers who blame them for being screwed.

This is the generation who remodelled their kitchen, with granite counter tops and exotic wood floors, and called it an investment. And it worked, that kitchen increased the purchasing power of their homes!

It was baby boomers, in the room applauding then-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dick Fisher. Fisher was asked in Q&A about the wealth effect. This is the term used by economists to describe the rise in GDP that occurs when asset prices rise.

“Let me just say,” he said with a broad smile, “the wealthy have been very affected!”

This room full of 1%ers, nearly all Baby Boomers as Keith recalls, applauded. Yes, wonderful. The Fed was making them richer. Increasing their purchasing power. By printing wealth, which is magic.

No, wait. The Fed can’t print wealth. So if the rich got richer, their nouveau riches did not come from the Fed and its magical printing press. Ahah, it came from the poor and the middle class. The Fed engineered a transfer.

No, wait. The poor don’t have any wealth. So logically, the rich didn’t get richer by stealing from them. And the middle class also feels richer, at least those who have assets do. So if everyone who has some wealth feels richer, then how do we explain this?

The wealth effect is wealth, the way pasteurized cheese food is cheese.

Which is to say, it’s not wealth. It makes people feel wealthier. It’s an analgesic, to dull the pain of the real loss of wealth they are suffering under a government, whose borrowing and spending has gone off the charts.

And now we get to the punchline. The Baby Boomers can no more earn interest than can their kids. Their yield purchasing power is falling.

The difference is that, unlike their kids, they have accumulated assets. So they can liquidate those assets to continue living their lifestyles. So long as asset prices keep rising, they may not see it as liquidation. They see it as buying and selling houses and cars and stocks. Or taking out a home equity loan. But whether the debt is on their own balance sheet or someone else’s, their generation is leveraging up to own assets. That is, they are borrowing and bidding up asset prices. And using rising asset prices to fuel consumption.

Borrowing, we must never forget, gives you the means to consume today in exchange for a promise to repay with interest. There is a seemingly infinite loop of borrowing backed not by more and more income, but by assets used as collateral.

Get that, consume today and pledge a house as collateral. And then sell it to consume more, while the buyer pledges the same old house as collateral for the loan that pays the seller and allows the seller to consume. Then the price rises, so he borrows more to fuel his own consumption.

It’s a seemingly endless process, of rising asset values and rising debt levels. The difference between them, is that the debt level is hard, but the asset price can get soft.

And it’s not endless. It has an end. Economics teaches us (or should teach us!) that consumption must be preceded by production. If a whole generation can seemingly get away with consuming above their production, thanks to the magic of rising asset prices, then they are consuming the capital stock which was previously produced.

We don’t know what the prices of the assets they will leave to their kids. But we do know that, net of debt, they will leave less real wealth.

This Report was written from Auckland. Keith is also visiting Sydney. If you would like to meet, please contact us.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

The price of gold rose $26, and the price of silver rose $0.44. And bitcoin fell $560.

Somebody should look into if the Fed and the Plunge Protection Team and the Bitcoin Banks are in cahoots to sell bitcoin naked-short…

Anyways, on a serious note, the S&P index fell 122. So far, this is the scenario towards which we said we are leaning. When the next bust hits, obviously stocks will dive (when the debt is impaired, the equity should be worth zero). And we said that after 7 years of a bear market, gold and silver are not likely much owned with leverage and therefore may not see price drops as they did in 2008 (which was after years of a bull market).

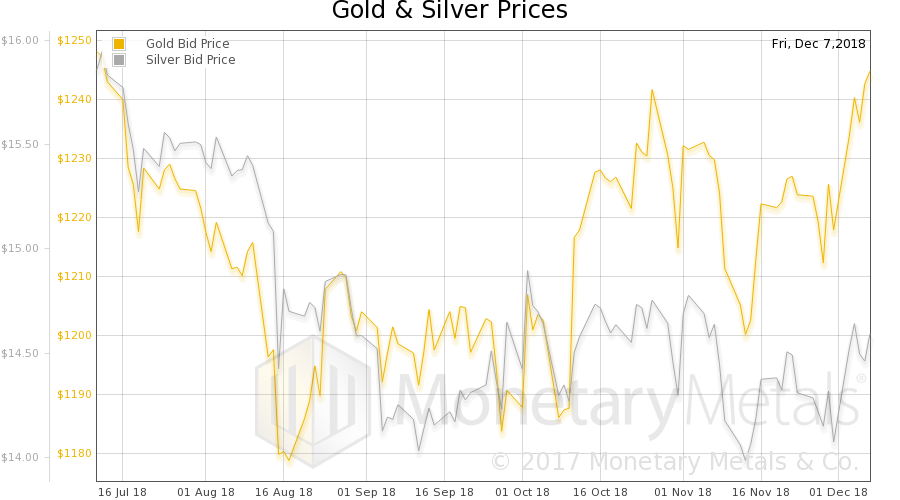

And while equities have had a rocky road since the beginning of October, the price of gold has been in a slight rising trend since then (silver, not so much).

Perhaps some of those Serious Right Thinking People will come to realize that they do need gold? Or maybe they will just buy it when next its price is obviously and significantly rising. You know, to make dollars (i.e. money). What else is good for? As Warren Buffet said, gold is “neither of much use nor procreative”…

Gold and Silver PricesThat’s sarcasm, by the way. We believe it’s good for financing productive activity. Better than the dollar in certain businesses. We would hate to predict that our own actions will be a driver for the gold price, but in this case, we do. When the world sees the re-emergence of gold bonds for the first time in 85 years, this will likely spur lots of people to buy gold. As to today, let’s look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals of gold and silver. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver. |

Gold and Silver Price(see more posts on gold price, silver price, ) |

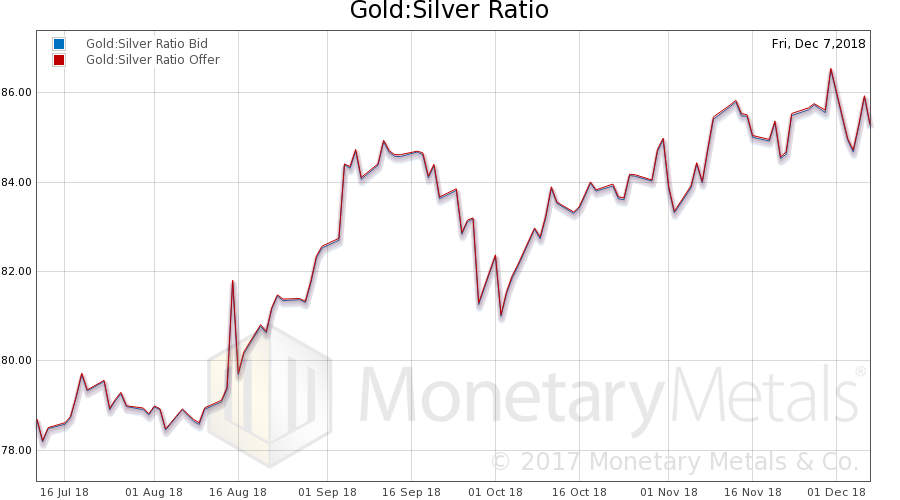

Gold:Silver RatioNext, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It fell this week. |

Gold:Silver Ratio(see more posts on gold silver ratio, ) |

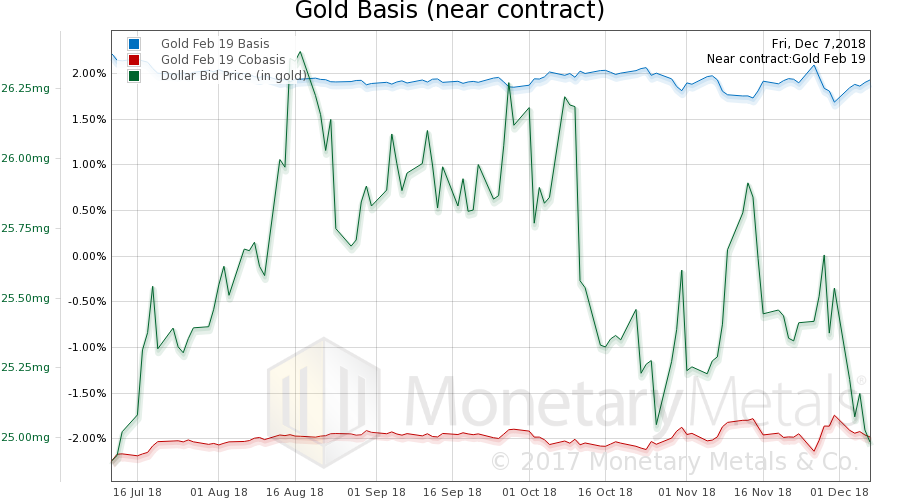

Gold Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar PriceHere is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price. We see a sizeable drop in the price of the dollar (inverse of the price of gold, which rose). And a slight drop in the scarcity of metal (i.e. cobasis). The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell another $6 this week to $1,293. This shows the value of the fundamental price. It shows that true supply and demand for the metal did not change much, even those the market price did. |

Gold Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar Price(see more posts on dollar price, gold basis, Gold co-basis, ) |

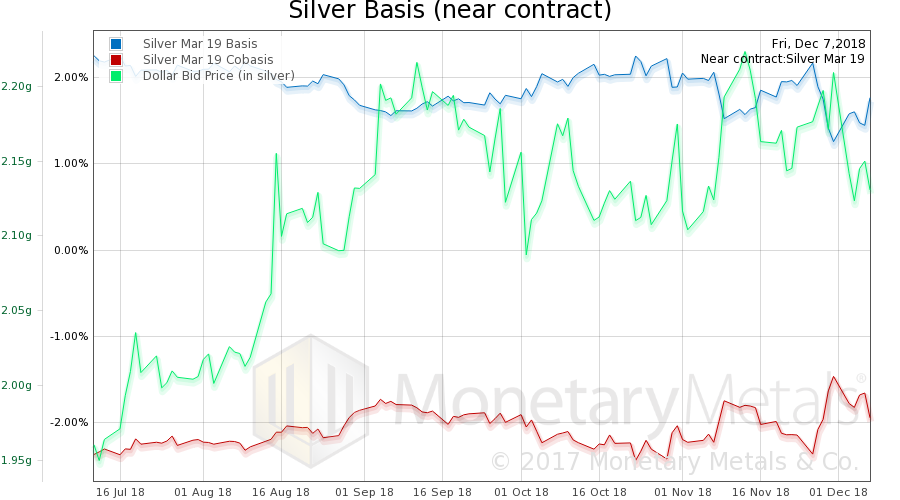

Silver Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar PriceNow let’s look at silver. In silver, we had an even bigger drop in the dollar price, proportionally. And a bit of a drop in scarcity of the metal, at the higher price of silver. And unlike in gold, the Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 13 cents, to $15.06. |

Silver Basis and Co-basis and the Dollar Price(see more posts on dollar price, silver basis, Silver co-basis, ) |

© 2018 Monetary Metals

Tags: Basic Reports,capital consumption,dollar price,falling interest,Featured,gold basis,Gold co-basis,gold price,gold silver ratio,newsletter,purchasing power,silver basis,Silver co-basis,silver price,yield purchasing power