In response to the coronavirus, central banks worldwide are currently pumping massive amounts of money. This pumping, it is held, is going to arrest the negative economic side effects that the virus-related panic inflicts on economies. As appealing as it sounds we suggest that this view is erroneous. The view that more money can revive an economy is based on the belief that money transmits its effect through aggregate expenditure. With more money in their pockets, people will be able to spend more and the rest will follow suit. Money then, as one can see in this way of thinking, is a means of payments and a means of funding. Money, however, is not the means of payments but the medium of exchange. It does not have a life of its own; it only enables one producer to

Topics:

Frank Shostak considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

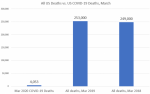

In response to the coronavirus, central banks worldwide are currently pumping massive amounts of money. This pumping, it is held, is going to arrest the negative economic side effects that the virus-related panic inflicts on economies. As appealing as it sounds we suggest that this view is erroneous.

In response to the coronavirus, central banks worldwide are currently pumping massive amounts of money. This pumping, it is held, is going to arrest the negative economic side effects that the virus-related panic inflicts on economies. As appealing as it sounds we suggest that this view is erroneous.

The view that more money can revive an economy is based on the belief that money transmits its effect through aggregate expenditure. With more money in their pockets, people will be able to spend more and the rest will follow suit. Money then, as one can see in this way of thinking, is a means of payments and a means of funding.

Money, however, is not the means of payments but the medium of exchange. It does not have a life of its own; it only enables one producer to exchange his produce for the produce of another producer.

The means of payments are always real goods and services, which pay for other goods and services. All that money does is facilitating these payments – it makes the payments for goods and services possible.

Thus, a baker exchanges his bread for money and then uses money to buy shoes. He pays for shoes not with money but with the bread, he produced. Money just allows him to make this payment. Also, note that the baker’s production of bread gives rise to his demand for money.

When we talk about demand for money, what we really mean is the demand for money’s purchasing power. After all, people do not want a greater amount of money in their pockets so much as they want greater purchasing power in their possession.

On this Mises wrote,

The services money renders are conditioned by the height of its purchasing power. Nobody wants to have in his cash holding a definite number of pieces of money or a definite weight of money; he wants to keep a cash holding of a definite amount of purchasing power. [1]

In a free market, in similarity to other goods, the price of money is determined by supply and demand. Consequently, if there is less money, its exchange value will increase. Conversely, the exchange value will fall when there is more money.

Within the framework of a free market, there cannot be such thing as “too little” or “too much” money. As long as the market is allowed to clear, no shortage of money can emerge.

Consequently, once the market has chosen a particular commodity as money, the given stock of this commodity will always be sufficient to secure the services that money provides. Hence, in a free market, the whole idea of the optimum growth rate of money is absurd.

According to Mises:

As the operation of the market tends to determine the final state of money’s purchasing power at a height at which the supply of and the demand for money coincide, there can never be an excess or deficiency of money. Each individual and all individuals together always enjoy fully the advantages which they can derive from indirect exchange and the use of money, no matter whether the total quantity of money is great, or small. . . . the services which money renders can be neither improved nor repaired by changing the supply of money. . . . The quantity of money available in the whole economy is always sufficient to secure for everybody all that money does and can do. [2]

In a market economy, the purpose of production is consumption. People produce and exchange with each other goods and services in order to promote their life and wellbeing – their ultimate purpose.

This in turn means that consumption cannot arise without production while production without consumption will be a meaningless venture. Hence, in a free market economy both consumption and production are in harmony with each other. In a free market economy, consumption is fully backed up by production.

What permits the baker to consume bread and shoes is his production of bread. Thus, a portion of his bread goes to his direct consumption while the other portion is used to pay for shoes.

Note that his consumption is fully backed up i.e. paid by his production. Any attempt then to raise consumption without the corresponding production leads to unbacked consumption, which must come at somebody else’s expense.

This is precisely what monetary pumping does. It generates demand, which is not supported by any production. Once exercised, this type of demand undermines the flow of real savings and in turn weakens the formation of real capital and stifles rather than boosts economic growth.

It is real savings and not money that fund and make it possible the production of better tools and machinery. With better tools and machinery it is possible now to lift the production of final goods and services – this is what economic growth is all about.

Hence, contrary to the popular way of thinking setting in motion an unbacked-by-production consumption by means of monetary pumping will only stifle and not promote economic growth.

This is because unbacked consumption will weaken the flow of real savings and thus weaken the source that funds real economic growth. If it had been otherwise then poverty in the world would have been eliminated a long time ago. After all everybody knows how to demand and to consume.

The only reason why in the past loose monetary policies seemed to grow the economy is because the pace of real savings generation was strong enough to absorb increases in unbacked consumption.

Once, however, the pace of unbacked consumption reaches a stage where the flow of real savings weakens the economy falls into a severe recession.

Any attempt by the central bank then to pull the economy out of the slump by means of more pumping makes things much worse for it only further strengthens unbacked or non-productive consumption, thereby destroying whatever is left of real savings.

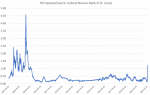

The collapse in the sources of real economic growth exposes commercial banks’ fractional reserve lending and raises the risk of a run on banks. Consequently, to protect themselves banks curtail the creation of credit out of “thin air”.

Under these conditions, further monetary pumping cannot lift banks’ lending. On the contrary, more pumping destroys more real savings and destroys more businesses, which in turn makes banks reluctant to expand lending.

Under these conditions, banks would likely agree to lend only to creditworthy businesses. However, as an economic slump deepens it becomes much harder to find many creditworthy businesses.

Even more, good businesses because of price deflation are reluctant to borrow. Furthermore, because of loose monetary policy the low interest return against the background of a growing risk further diminishes banks’ willingness to expand credit. All this puts downward pressure on the stock of money.

Hence, the central bank may find that despite its attempt to inflate the economy money supply will start falling. Obviously, the Fed could offset this fall by aggressive monetary pumping.

The central bank could monetize the government budget deficit – it could mail checks to every citizen of the US. All this, however, will only further undermine real savings and devastate the real economy.

But surely the government and the central bank should be doing something to prevent the economic deterioration because of the coronavirus. Unfortunately, neither the central bank neither the government have the real resources to grow an economy.

Neither the central bank nor the government are wealth generators they are supported by diverting resources from the wealth-generating private sector.

This means that any measures that the government is going to undertake must be at the expense of activities that are generating wealth. Needless to say that this will weaken the ability of the economy to generate goods and services.

Hence, regardless of good intentions neither the central bank nor the government are capable to help the economy to counter the damage inflicted by the coronavirus. Only the wealth-generating private sector could do it.

The critics of our way of thinking argue that monetary pumping creates a temporary illusion of richness and this is going to boost the demand for goods and services. On this way of thinking, an increase in the demand will trigger an increase in the supply i.e. in the production of goods and services.

We have however, seen that without the increase in real savings it is not possible to increase the production of goods and services. Hence if the ability of the economy has been damaged boosting the demand is not going to repair the damage if the flow of real savings was weakened.

Tags: Featured,newsletter