One of the most commonly cited arguments initially against Brexit, and now against a no-deal scenario, is the towering threat of businesses leaving the UK. A great many campaigners and leading figures of the Remain camp have warned voters time and time again of the dangers to British industry and ultimately to their jobs. They will often point to early evidence of such a shift, to companies moving either their headquarters or part of their operations to Germany, the Netherlands or other EU member states. They also like to highlight the concerns of various business leaders that have taken the Remain position, while some have supported the idea of a “People’s Vote”, a second referendum that they hope will reverse the original decision. The dire warnings and the near-apocalyptic visions

Topics:

Claudio Grass considers the following as important: Economics, Finance, Gold, Politics

This could be interesting, too:

Investec writes The Swiss houses that must be demolished

Claudio Grass writes The Case Against Fordism

Claudio Grass writes “Does The West Have Any Hope? What Can We All Do?”

Investec writes Swiss milk producers demand 1 franc a litre

One of the most commonly cited arguments initially against Brexit, and now against a no-deal scenario, is the towering threat of businesses leaving the UK. A great many campaigners and leading figures of the Remain camp have warned voters time and time again of the dangers to British industry and ultimately to their jobs. They will often point to early evidence of such a shift, to companies moving either their headquarters or part of their operations to Germany, the Netherlands or other EU member states. They also like to highlight the concerns of various business leaders that have taken the Remain position, while some have supported the idea of a “People’s Vote”, a second referendum that they hope will reverse the original decision.

The dire warnings and the near-apocalyptic visions of post-Brexit destruction have managed to gather wide media coverage, with panic-stricken headlines like the BBC’s “Brexit threat to sandwiches” and the Independent’s “Butter, yogurt and cheese could become occasional luxuries after Brexit”. However, what is hardly ever mentioned is the failure of most of these projections to materialize, at least so far. What is also frequently omitted in the discussions over the fears of businesses leaving the UK, are the departures that already took place while the UK was still in the EU.

Much ado about nothing?

Early in the Brexit campaign, Remainers published extensive research and projections regarding the potential job losses and company relocations should the Leave camp prevail. After it did, the numbers kept coming, with predictions of a mass exodus of jobs and business. The finance sector soon emerged as the one most likely to suffer the heaviest losses, with terrifying analyses like that by Oliver Wyman, warning that a hard Brexit could result in a loss of 75,000 jobs and £10bn of tax revenue. And yet, by last September, only 630 UK-based finance jobs had actually moved, according to a Reuters survey, a mere fraction of the estimates. More recent projections have been slashed, reflecting a much milder impact and highlighting the degree of exaggeration in previous predictions.

Overall, the concerned voices and the doom-and-gloom narratives coming out of the business world have also been largely proven hyperbolic and inaccurate, at least up to this point. Moreover, strong counterarguments have gained traction, as a few well-respected and successful businessmen and women have publicly adopted a much calmer and more confident outlook for the post-Brexit reality in the UK. Sir James Dyson, billionaire inventor, has described his expectations for trade as “enormously optimistic”, while Sir Jim Ratcliffe, the wealthiest man in the UK, also expressed similar views: “The Brits are perfectly capable of managing the Brits and don’t need Brussels telling them how to manage things”.

The split in the business world

At the same time, it has become apparent that the interests of small businesses and large corporations are not at all aligned when it comes to Brexit. Among the most vocal and fervent Remainers and supporters of the idea of a second referendum, one finds a large share of executives and representatives from the corporate arena, together with industry lobbyists. On the other hand, small and family business owners are much more likely to support to be optimistic over Brexit. According to the Daily Telegraph’s Business Tracker, small firms have a positive outlook, despite mounting concerns over Brexit, as positive sentiment vastly overshadowed negative sentiment in 2018.

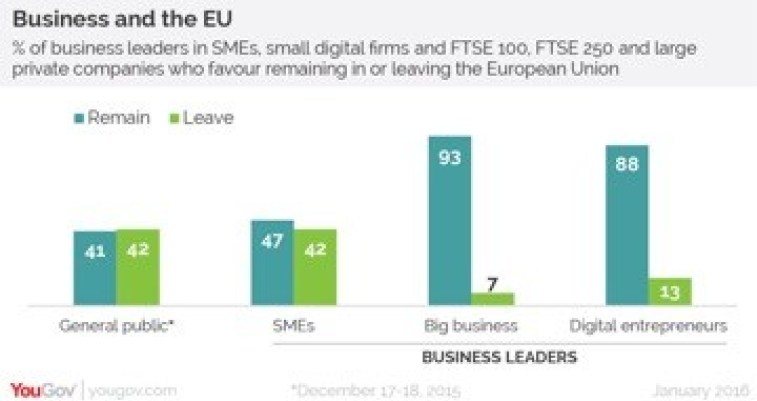

All in all, small business owners have been inclined to be more Eurosceptic than their much larger and multinational counterparts. That sentiment reinforces the idea that Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) owners are much more in touch with the realities on the ground than senior figures in FTSE companies or Tech entrepreneurs, whose views were statistically massively out of sync with the public.

Official figures from YouGov, also indicate that the smaller the company, the less likely they are to support retaining EU membership. Such findings are even more significant when one considers that SMEs account for 60% of all private sector employment in the UK and 47% of private sector turnover.

Sins of Omission

During the many debates on the future of the business world, a lot of attention and airtime is given to the fears that businesses will leave as a result of Brexit. However, the ones that have already left during the country’s membership, are seldom mentioned. Although various claims and reports on this issue are riddled with inaccuracies and have wildly exaggerated the number of these relocation cases, there is still a factual basis and numerous solid examples of instances when EU funding or other incentives encouraged companies to move operations out of the UK.

In 2012, Ford relocated the production of Ford Transit vans to a factory in Turkey, a move that was facilitated by an £80m loan approved by the European Investment Bank and cost the UK more than 500 jobs. In 2011, Twinning’s Tea tried and came very close to securing a €12m grant for a factory in Poland, while planning to cut 400 jobs in the UK. The grant was denied at the last minute, after accusations of breached EU rules and the subsequent media attention. In 2018, EU leadership in Brussels approved a bid by Slovakia to provide €125m in funding for a new Jaguar Land Rover plant, a move that has raised considerable objections and concerns over lost jobs in the UK.

Lost faith in government

As the government’s approval rating has taken a nosedive since the negotiations began, the public’s doubts over the leadership’s ability to handle the exit process and to deliver on what they voted for have spiked. After Theresa May’s performance during the talks with the EU and her failure to secure the assurances she promised, confidence in her government has plummeted. Official statements and commitments have largely lost their credibility, to the point that despite repeated assurances against a no-deal exit, the public still believes this is the most likely scenario. Moreover, a survey by the Enterprise Investment Scheme Association (EISA) showed that 59% of UK investors do not think the government is doing a good job in negotiating a deal that would protect the interests of the UK’s financial services sector.

Source: Bloomberg, Opinium

At the same time, the EU is sticking to its extremely hard stance on the matter, firmly refusing any meaningful concessions and sharply focused on making an example out of the UK, rather than achieving a sustainable and mutually beneficial deal. Recent comments by European Council President Donald Tusk exemplified this vindictive position, as he gleefully mentioned a “special place in hell” for “those who promoted Brexit”.

No matter how this ends, the damage already done to the British public and the country’s social cohesion is considerable. Deep divisions, fuelled and aggravated by both the media and by political figures, will not heal easily. Civilized conversation and free debate on the topics that really matter have long given way to personal attacks and name-calling. Such a devolution and corrosion of civil dialogue is bound to have a lasting and widespread impact on British society and on the country’s political future.

However, despite all the noise, one thing is clear: the United Kingdom will eventually regain its national sovereignty, one way or another. Delays are likely, and so are potential political maneuvers to void the public’s will, which are destined to fail. Today, the main focus might lie in a Hegelian dialectic, in divisive tactics and in massive fearmongering campaigns, nevertheless, the country is on track to free itself from the centralized authority of Brussels. The only real question is how this regained freedom will be channeled. Will the government use it to enforce an even more centralized system than today on a national level, or will it empower the individual and take a turn towards more personal responsibility and self-determination?

Either way, it is bound to be a bumpy and eventful road ahead for the UK and for the EU as well, as the scars of Brexit are still fresh. Dissatisfaction with Brussels is far from a confined phenomenon and dissenting voices continue to get louder all over the continent. From an investor’s perspective, preparing for the very likely political and economic turbulence that awaits is essential. With European markets under pressure, a near-impotent Central Bank and a currency that will struggle when the next downturn commences, physical precious metals and their lack of counterparty risk provide a much-needed hedge and a way to protect one’s wealth.

Although it’s impossible to predict the ultimate outcome of this historic turning point, Britain appears to be on the right track, especially if the British people will remember and hopefully be guided by Lord Acton’s words: “Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end.”

Claudio Grass, Hünenberg See, Switzerland

This article has been published in the Newsroom of pro aurum, the leading precious metals company in Europe with an independent subsidiary in Switzerland. All rights remain with the author and pro aurum.