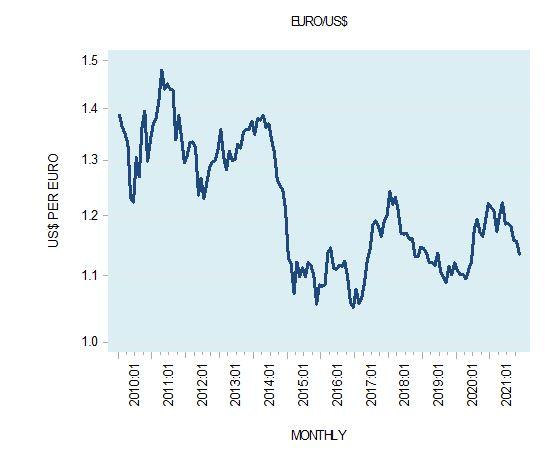

The price of the euro in terms of the US dollar closed at 1.135 in November, against 1.156 in October and 1.193 in November last year. The yearly growth rate of the price of the euro in US dollar terms fell to –4.8 percent in November from –0.7 percent in October. Some commentators are of the view that the US dollar is likely to weaken against the euro (i.e., the price of the euro in US dollar terms is likely to increase). The reason for this is the massive US trade balance deficit. . In September 2021 the US trade balance stood at a deficit of .9 billion, against a deficit of .6 billion in September last year (see chart). Again, some commentators regard a widening in the trade deficit as an ominous sign for the exchange rate of the US dollar against

Topics:

Frank Shostak considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| The price of the euro in terms of the US dollar closed at 1.135 in November, against 1.156 in October and 1.193 in November last year. The yearly growth rate of the price of the euro in US dollar terms fell to –4.8 percent in November from –0.7 percent in October. Some commentators are of the view that the US dollar is likely to weaken against the euro (i.e., the price of the euro in US dollar terms is likely to increase). The reason for this is the massive US trade balance deficit. | |

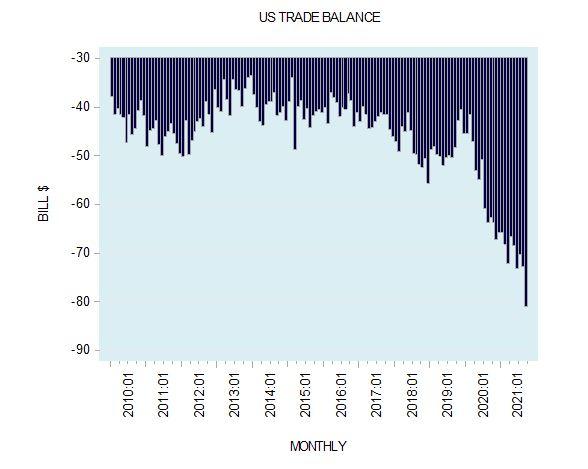

| In September 2021 the US trade balance stood at a deficit of $80.9 billion, against a deficit of $62.6 billion in September last year (see chart). Again, some commentators regard a widening in the trade deficit as an ominous sign for the exchange rate of the US dollar against major currencies in the times ahead. | |

| For most economic commentators, a key factor in determining the currency rate of exchange is the trade account balance. In this way of thinking, a trade deficit weakens the price of the domestic money in terms of foreign money while the trade surplus works toward the strengthening of the price.

By this logic, if a country exports more than it imports, there is a strengthening in the relative demand for its goods, and thus for its currency, so the price of the local money in terms of foreign money is likely to increase. Conversely, when there are more imports than exports, there is relatively less demand for a country’s currency, so the price of domestic money in terms of foreign monies should decline. Similarly, following this way of thinking, all other things being equal, if for some reason there is a sudden increase in foreigners’ demand for a country’s currency, this is going to strengthen the currency rate of exchange versus other currencies. If, however there is a sudden decline in foreigners’ demand for a country’s currency, this is going to weaken the currency rate of exchange against other currencies. Notwithstanding, this way of thinking is questionable. Here is why. |

The Purchasing Power of Money and the Supply and Demand for Money

The subject matter of the currency rate of exchange is the price of one money in terms of another money. The rate of exchange of a given money with respect to something is the amount of money paid per unit of something. Alternatively, we can say that the price of something is the amount of money paid for it. The amount of money paid for something is the money’s purchasing power with respect to something.

If the supply of money increases, the purchasing power of money with respect to the given stock of goods is going to weaken, since now there is more money per good.

Conversely, for a given stock of money, an increase in the production of goods implies that there are now more goods per unit of money. This means that, all other things being equal, the purchasing power of money with respect to goods is going to strengthen.

For example, let us say we observe that a given basket of goods is exchanged in the US for one dollar and the same basket of goods is exchanged for two euros in Europe. This means that the purchasing power of one dollar is this basket of goods in the US. It also means that the purchasing power of two euros is this basket of goods in Europe.

We can infer from this that, all other things being equal, the rate of exchange between the US dollar and the euro is going to be one dollar for two euros. Any deviation of the exchange rate from the level dictated by the purchasing power of the currencies will set corrective forces in motion.

Suppose that because of a US trade surplus and the consequent relative increase in the demand for US dollars the rate of exchange was set in the market at one dollar for three euros. In this case, the dollar is now overvalued in terms of its purchasing power versus the purchasing power of the euro.

Because of the strengthening of the dollar due to the trade balance surplus, it will pay to sell baskets of goods for dollars, exchange the dollars for euros, and then buy baskets of goods with euros—thus making a clear arbitrage gain.

For example, individuals are going to sell a basket of goods for one dollar, exchange the dollar for three euros, and then exchange the three euros for 1.5 basket of goods, gaining an extra half basket of goods.

The fact that the holders of dollars are going to increase their demand for euros in order to profit from the arbitrage is going to make euros more expensive in terms of dollars and this in turn is going to push the exchange rate back in the direction of one dollar to two euros.

Why the Trade Balance Is not the Fundamental Cause of Exchange Rate Determination

In order to establish that the trade balance determines the currency rate of exchange, we need to show that the trade balance determines the purchasing power of money.

Only central bank monetary policies and fractional reserve banking can determine the supply of money. Similarly, the balance of trade does not determine the amount of goods produced, which determines the demand for money. The balance of trade only records the value of given goods bought and sold by an individual or a group of individuals. Since the trade balance as such has nothing to do with either the supply of money or the demand for money, we can conclude that trade balances do not determine the purchasing power of a country’s money.

This is not to say that relative changes in exports or imports as mirrored by the trade balance do not influence the currency rate of exchange, but rather that these changes are not the fundamental causes of the exchange rate determination. Consequently, the influence of these changes is likely to vanish over time as the currency rate of exchange converges toward its fundamental value as dictated by the relative purchasing power of money.

Changes in the Relative Money Supply Growth and Currency Exchange Rate

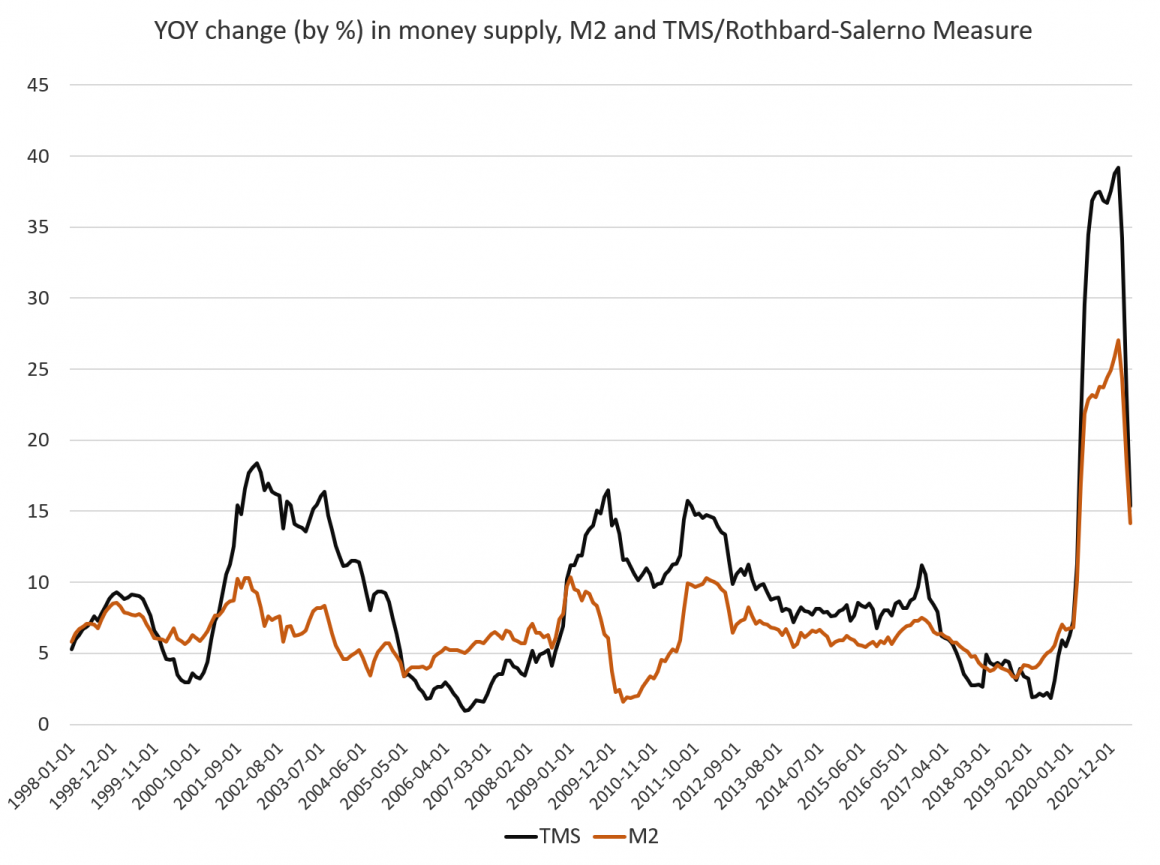

Again, what matters for the determination of the currency exchange rate is a currency’s purchasing power relative to a basket of goods. With all other things being equal, a major factor behind the change in the purchasing power of money is changes in the supply of money.

Thus, an increase in the supply of dollars implies a greater amount of dollars on offer for the basket of goods. This means a decline in the purchasing power of dollars with respect to the basket of goods. Likewise, a decline in the supply of euros for the same basket of goods implies a smaller amount of euros for the basket of goods. This means an increase in the purchasing power of the euro with respect to the basket of goods.

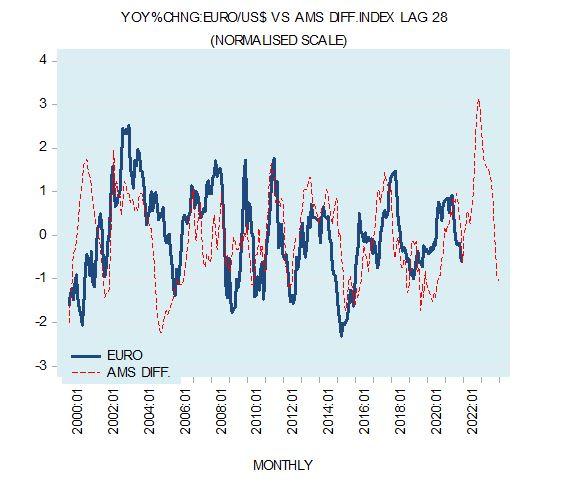

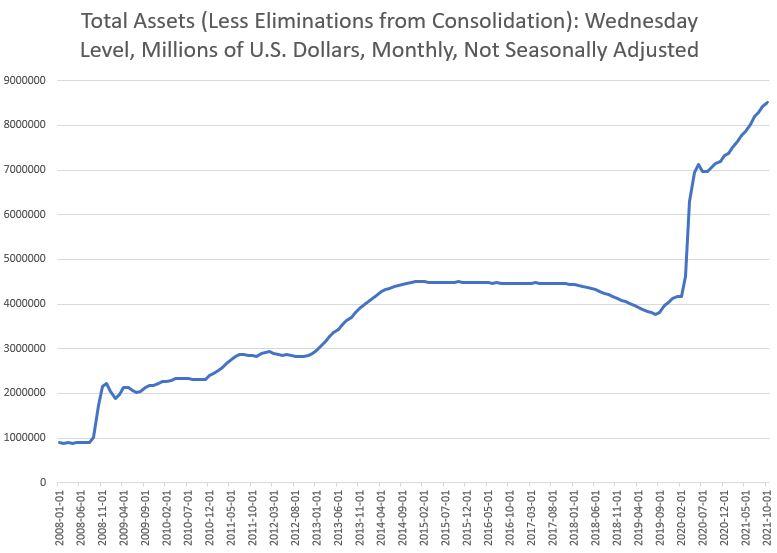

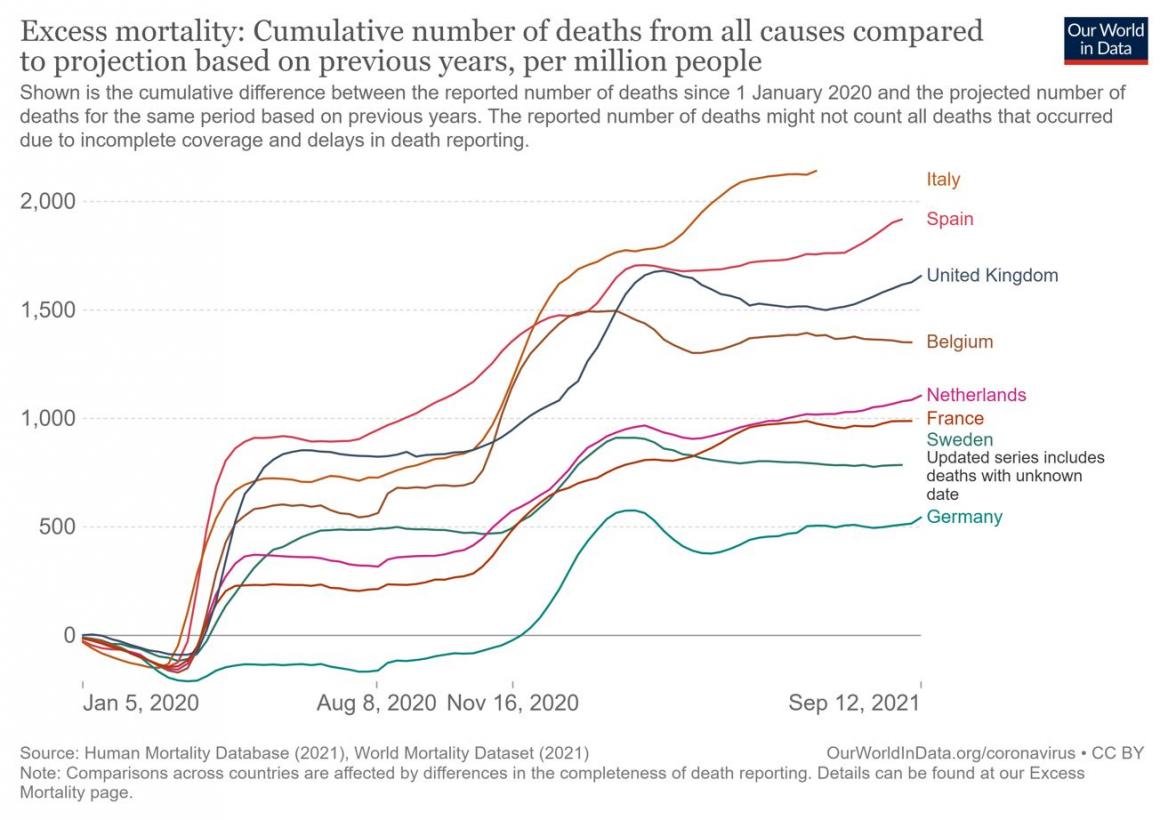

Hence, over time, if the growth rate of the US money supply exceeds the growth rate of the eurozone money supply, with all other things being equal, the US dollar is going to depreciate against the euro. The lagged money growth differential between the US money supply and the eurozone money supply suggests that the momentum of the price of the euro in terms of the US dollar is likely to strengthen sharply during 2022 (see chart below). This could mean that the US dollar is likely to visibly weaken against the euro.

Fundamental versus Nonfundamental Causes

Often various nonfundamental factors are perceived to be important in determining a currency’s rate of exchange because “it feels right.” A sharp widening in the trade deficit is regarded as a sign of a likely deterioration in economic fundamentals ahead. This provides the rationale for the selling of the currency of concern.

Alternatively, let us say that an analyst forms a view that the growing US government debt at some stage will likely cause foreigners to stop buying US Treasurys. Consequently, with all other things being equal, this is going to lower the demand for dollars and result in the dollar’s collapse. It would appear that various factors such as the government debt, the interest rate differential, the state of the economy, and the balance of trade could be employed to illustrate a scenario of a collapsing dollar. But all this amounts to curve fitting.

What matters for currency exchange rate determination is the relative changes in the purchasing power of the respective currencies. All other things being equal, one can infer that a major driving factor in exchange rate determination is the relative change in currencies’ respective money supplies. Again, various nonfundamental factors are likely to influence currencies’ rate of exchange as well; however, arbitrage will push the exchange rates back toward their fundamental values as dictated by the relative growth rates in money supplies.

Tags: Featured,newsletter