Last month, British black studies professor Kehinde Andrews argued that the British Empire was “far worse than the Nazis.” It was a controversial comparison to be sure, but it raises the question: Compared to other expansionist regimes, how bad was the British Empire? A survey of the evidence suggests that the British Empire was relatively less harmful than other imperial efforts, and this is reflected in outcomes—in terms of health and economic growth, among other outcomes—compared among British colonies and other sovereign states in similar times and places. This should not surprise us, since, as far as empires go, the British one was unusually liberal and open in terms of trade, centralization, and economic regulation. One can certainly argue that colonial

Topics:

Lipton Matthews considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Last month, British black studies professor Kehinde Andrews argued that the British Empire was “far worse than the Nazis.” It was a controversial comparison to be sure, but it raises the question: Compared to other expansionist regimes, how bad was the British Empire?

Last month, British black studies professor Kehinde Andrews argued that the British Empire was “far worse than the Nazis.” It was a controversial comparison to be sure, but it raises the question: Compared to other expansionist regimes, how bad was the British Empire?

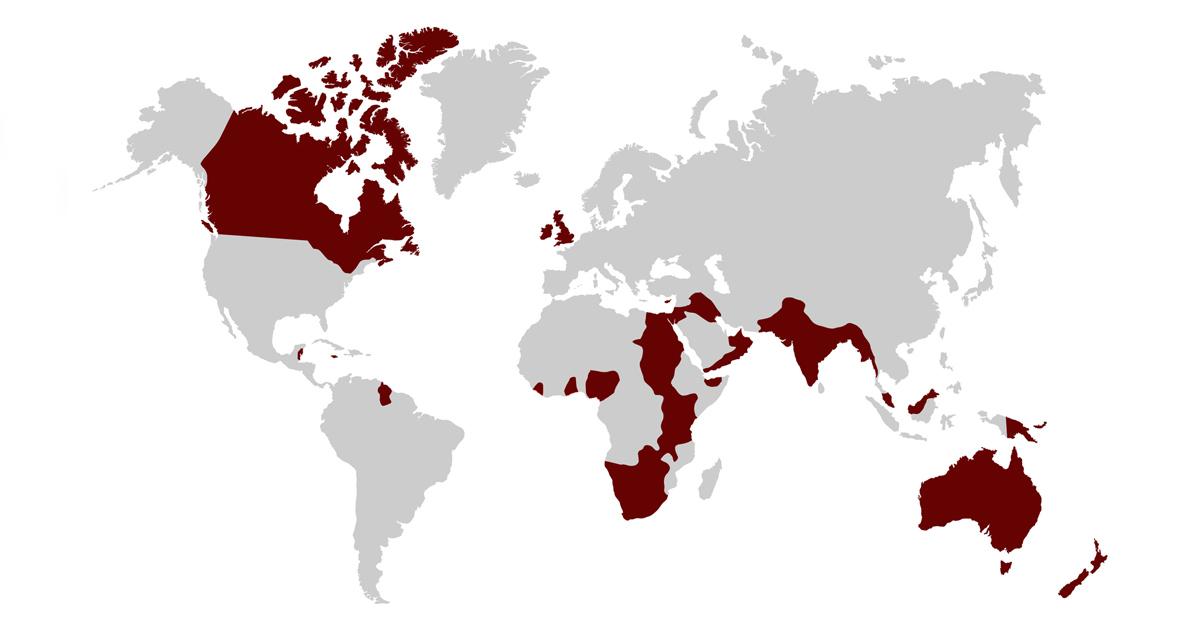

A survey of the evidence suggests that the British Empire was relatively less harmful than other imperial efforts, and this is reflected in outcomes—in terms of health and economic growth, among other outcomes—compared among British colonies and other sovereign states in similar times and places.

This should not surprise us, since, as far as empires go, the British one was unusually liberal and open in terms of trade, centralization, and economic regulation.

One can certainly argue that colonial empires are in themselves morally unacceptable—as Ludwig von Mises did—but the fact that colonial empires often differ significantly in their outcomes can serve to provide us with insights into what sorts of government policies are the most and least harmful.

British vs. French Education Policy

For example, Bolt and Bezemer (2008) assert that differences in human capital among former colonies are explained by the identity of the colonizing power. Unlike the French, who sought to centralize education and often clashed with missionaries, the British provided missionaries with greater latitude to design curricula. Missionaries were even given the option to contextualize education to meet the needs of natives. Whereas the French aimed to train a cadre of officials who were assimilated into French culture, British officials promoted an inclusive approach. Furthermore, by popularizing vocational education the British enabled locals to obtain technical skills that aided in boosting human capital.

Similarly, Agbor (2011) submits that the educational policy of the British is a mechanism through which colonial origin impacts economic growth in African countries during 1960–2000. The British felt that education should solve the problems of colonial society, hence they adopted an indirect approach allowing instruction to be administered “through village schools using native teachers and the local vernacular languages of the people, whilst in former French colonies, pupils were generally boarded from their homes to far away schools where they were taught in French by French teachers, using French textbooks.” As a result, the practical outlook of the British was more favorable to natives, who acquired useful skills, in contrast to the selective model of the French, who invested in creating an elite crop of bureaucrats to administer colonial policy. These findings have been confirmed by recent research identifying an educational advantage for adults born in the British part of Cameroon compared to their peers from French Cameroon.

Economic Growth

Historically, Britain has been more committed to free trade than other European powers. For example, in the nineteenth century, British colonies were never obliged to export solely to Britain. Hence economist Julius Agbor opines that “one of the most important legacies of British colonisation on its former colonies has been a long exposure to world competition through trade openness, which might possibly explain why former British sub-Saharan colonies adjusted more rapidly through structural adjustment programmes implemented in the 1980s in comparison with their French counterparts.”

Moreover, Bertocchi and Canova (2002) contend that, on average, British ex-colonies report superior economic performance to French ex-colonies. This is consistent with the earlier research of Grier, who attributes the stronger economic performance of former British colonies to educational policy. Likewise, Agbor in a recent study informs readers that “former British colonies have had marginally higher income levels than former French colonies during 1960–2000, and that this is attributable to the favourable contribution of the legacy of British colonisation in trade openness and human capital.”

Health

Based on his assessment of health policy in colonial Kenya, Moradi (2009) concludes that “the net outcome of colonial times was a significant progress in nutrition and health.” He continues: “Colonial times were not as bad as commonly believed. In fact, Kenya … outperformed places like Mexico and India.” Additionally, Klerman et al. (2011) concur with him by noting that life expectancy in former British colonies was significantly higher around 1960.

Flexible Labor Markets

For years economists have posited that the common law is flexible and more conducive to investment than civil law. As such, countries with a common law legal system report dynamic labor markets and lower levels of regulation. According to Botero et al. (2013), heavy regulation of labor is associated with lower labor force participation and higher unemployment, especially among young people. Singapore is a perfect example of a former British colony that successfully appropriated British institutions, as Shankar Singham points out in a recent piece:

Singapore embraced open trading regimes, open and competitive markets, property rights protection and the rule of law…. This was the result of deliberate choices made by political leaders, in particular Lee Kuan Yew, who, as Prime Minister from 1959 to 1990, embedded English common law. Having returned from Cambridge, he was impressed by the power of the common law to support business and encourage investment by balancing the competing rights of market participants in a flexible and yet certain way. By contrast civil law, which operates on the basis of statutes rather than precedents, can be rigid and legalistic.

The Postcolonial Rejection of Liberalism

Obviously, some are wondering why many former British colonies do so poorly even though British institutions seem to generate progress. Yet this irony is easily explained by the policies of postcolonial leaders. After gaining independence in 1962, the Jamaican economy experienced record economic growth. But unlike the pragmatic Lee Kuan Yew, who sought to transform Singapore into a competitive economy, Jamaica had the idealistic Michael Manley.

Under the spell of democratic socialism, he aggressively advocated statist policies, thus inducing economic collapse. Economist Peter Blair Henry in “Institutions vs. Policies: A Tale of Two Islands” illustrates the terrible effects of the Manley years:

In 1972 the People’s National Party (PNP) rose to power under the leadership of Prime Minister Michael Manley and the promise of “democratic socialism.” The two cornerstones of democratic socialism and the PNP’s economic policies were “self-reliance” and “social justice.” Self-reliance translated as extensive state intervention in the economy. The PNP nationalized companies, erected import barriers in the form of higher tariffs and outright bans, and imposed strict exchange control…. Whatever merits the PNP’s economic program may have had, it was expensive. Government spending rose from 23 percent of GDP in 1972 to 45 percent of GDP in 1978. Revenue did not keep pace with the rise in expenditure. From 1962 through 1972 Jamaica’s average fiscal deficit was 2.3 percent of GDP…. In contrast, from 1973 to 1980 the average fiscal deficit was a whopping 15.5 percent of GDP…. By 1980 inflation was 27 percent per year, investment had collapsed (to 14 percent of GDP down from 26 percent in 1972), and the PNP was voted out of power.

Apologists for the Manley regime usually ascribe economic turmoil to external shocks, like the oil crisis of the 1970s, but economist Derick Boyd avers that this view is untenable:

The economy’s structure and the policies followed by the Michael Manley government were important contributing factors in the decline. The government pursued its primary social objectives refusing to recognize the constraints imposed by the persistent balance of payments disequilibria on an open economy, holding to this course as long as it could. The subsequent result of this and other factors brought about rapid social and economic decline which attracted the attention of the world.

Andrews’s attempt at comparing the British colonial experience to that of the Nazi conquests should be regarded as obvious hyperbole. But even when far more mild comparisons are made—such as with the French colonies—we find it was the relatively liberal British who left behind colonies that were comparatively heathier, more educated, and more economically developed than was the case where there was less embrace of free trade and economic freedom.

Tags: Featured,newsletter