Technology is the main reason why so many of us are still alive to complain about technology. —Garry Kasparov If I take 30 steps linearly, I get to 30. If I take 30 steps exponentially, I get to a billion. —Ray Kurzweil While world leaders try to decide whether their interests are best served by World War III or some other imposed atrocity, various forces have states targeted for extinction. Chief among these forces is the exponential nature of evolution and technology, working together to advance human life. The other threat to the state’s existence is untreated self-inflicted wounds, which I’ll discuss later. Let’s start with evolution. Shortly after the big bang, atoms started forming, then later, atoms combined into molecules. Carbon in particular gave rise to

Topics:

George Ford Smith considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Technology is the main reason why so many of us are still alive to complain about technology.

If I take 30 steps linearly, I get to 30. If I take 30 steps exponentially, I get to a billion.

While world leaders try to decide whether their interests are best served by World War III or some other imposed atrocity, various forces have states targeted for extinction. Chief among these forces is the exponential nature of evolution and technology, working together to advance human life. The other threat to the state’s existence is untreated self-inflicted wounds, which I’ll discuss later.

Let’s start with evolution. Shortly after the big bang, atoms started forming, then later, atoms combined into molecules. Carbon in particular gave rise to more complicated structures. As renowned inventor, entrepreneur, and futurist Ray Kurzweil writes in his magnum opus, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology,

It’s clear that the physical laws of our universe are precisely what they need to be to allow for the evolution of increasing levels of order and complexity . . . carbon-based compounds became more and more intricate until complex aggregations of molecules formed self-replicating mechanisms, and life originated. Ultimately, biological systems evolved a precise digital mechanism (DNA) to store information describing a larger society of molecules.

DNA-guided evolution led to organisms that could detect and process information and store it in their brains and nervous systems. Eventually early life forms began to detect patterns, then later, humans evolved the ability to form abstractions about the world. When man developed an opposable thumb, he began creating methods that improved his chances of survival, such as using a long stick to reach high-hanging fruit.

He also learned that he could drive off competitors for the fruit by threatening them with the stick. Technology evolved as something with more than one edge.

The Law of Accelerating Returns

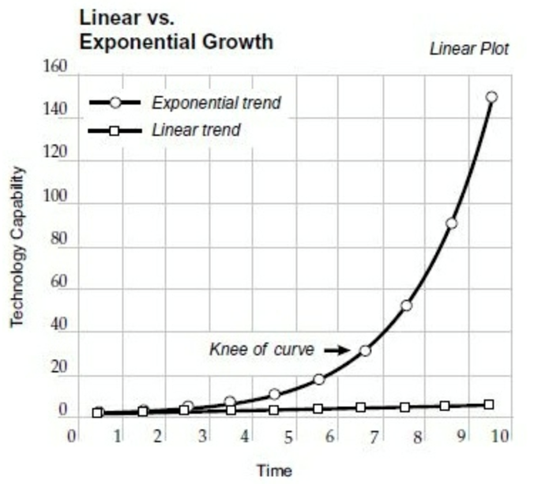

What is not often understood about evolutionary processes is that they progress along an exponential curve. The exponential nature of the progression is not obvious in its early stages, and even in advanced stages such as information technology today, progress doesn’t seem all that profound. The reason is that even an exponential will seem linear over a short-enough time span—even after it reaches the knee of the curve, defined as the point where y-axis values begin to rapidly increase.

Figure 1: Linear versus exponential growth

The subtle power of the exponential is revealed in a 2013 Mother Jones article, as I discussed in my book The Fall of Tyranny, the Rise of Liberty:

Imagine if Lake Michigan were drained in 1940, and your task was to fill it by doubling the amount of water you add every 18 months, beginning with one ounce. So, after 18 months you add two ounces, 18 months later you add four ounces, and so on. Coincidentally, as you were adding your first ounce to the dry lake, the first programmable computer in fact made its debut.

You continue. By 1960 you’ve added 150 gallons. By 1970, 16,000 gallons. You’re getting nowhere. Even if you stay with it to 2010, all you can see is a bit of water here and there. In the 47 18-month periods that have passed since 1940, you’ve added about 140.7 trillion ounces of water. You’ve done a lot of work but made almost no progress. You break out a calculator and find that you need 144 quadrillion more ounces to fill the lake.

You’ll never finish, right? Wrong. You keep filling it as you always have, doubling the amount you add every 18 months, and by 2025 the lake is full.

In the first 70 years, almost nothing. Then 15 years later the job is finished.

A famous quote from Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises suggests an exponential process when one of the characters was asked how he went bankrupt: “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”

In his book The Age of Intelligent Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence, Kurzweil makes the same point with a real-world example: “Consider Garry Kasparov [World Chess Champion (1985–2000)], who scorned the pathetic state of computer chess in 1992. Yet the relentless doubling of computer power every year enabled a computer to defeat him only five years later.”

In 2020 Kasparov put his loss in perspective, saying his defeat was sobering and that artificial intelligence (AI) development is moving too slow rather than too fast. Yet many (though not, as you might expect, Ray Kurzweil) believe we’re being replaced by machines. Speaking at the Council on Foreign Relations five years ago, Kurzweil said: “AI will benefit us in the same way that previous technologies have. My view is not that AI is going to displace us. It’s going to enhance us. It does already.”

Those fearful of tech innovation want to know if anything can stop it. According to Kurzweil, there is:

When I started my optical character recognition (OCR) and speech-synthesis company (Kurzweil Computer Products) in 1974, high-tech venture deals in the United States totaled less than thirty million dollars (in 1974 dollars). Even during the recent high-tech recession (2000–2003), the figure was almost one hundred times greater. We would have to repeal capitalism and every vestige of economic competition to stop this progression. [my emphasis]

The World Economic Forum Has Big Plans for Us

Catchphrases like “the Green New Deal,” “the Great Reset,” “Build Back Better,” “climate change,” “the Fourth Industrial Revolution”—along with the recent covid pandemic—signal an orchestrated attempt to repeal what’s left of capitalism.

It won’t work. Projects need funding, and the inflatable money states are using, which has undergone perpetual debasement since the creation of the Bank of England in 1694 and especially since the Fed opened its doors in late 1914, is nosediving to zero. Switching to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) might have saved them, but Schwab and company have lost too much trust to pull it off. People will reject CBDCs and the organizations that promote them, and states will die off from their self-inflicted wounds.

As Newsweek author Aubrey Strobel put it, “CBDCs are a wolf in sheep’s clothing, co-opting Bitcoin’s appeal while undermining every one of its underlying principles.”

We’ll still be riding the exponential superjet, with a lot less violent (government) interference.

The Fermi Paradox

Yet there’s still a chilling effect from technological advance when we consider earth’s place within the universe. Humans are likely not the only ones driving technology.

If this is true, why haven’t we heard from any other civilization (a question raised by physicist Enrico Fermi in 1950)? Surely on some planet somewhere there are civilizations far more advanced than any on earth, and not just by a few decades. And it’s not as if searches for extraterrestrial intelligence have lacked support, monetarily or otherwise, as the long history of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence makes clear. Kurzweil supposes, “Most of those that are ahead of us would be ahead by millions, if not billions, of years. . . . The skies should be ablaze with intelligent transmissions. Yet the skies are quiet.”

Does the silence mean that at some point intelligent life self-destructs? He thinks not. With so many possible civilizations, “It is not credible to believe that every one of them destroyed itself.”

If Kurzweil is right, then at least one civilization has managed to live without coercion being central to its existence—in contrast to earth’s states where it is their defining characteristic. As Ludwig von Mises made clear in Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War, “The total complex of the rules according to which those at the helm [of the state] employ compulsion and coercion is called law. Yet the characteristic feature of the state is not these rules, as such, but the application or threat of violence.”

It’s not surprising, then, with states in their death throes, that many people see planet earth approaching some kind of existential disaster. Yet as Steven Pinker has argued at length in his data-rich book The Better Angels of Our Nature, the world is less violent today than ever before. “Across time and space, the more peaceable societies . . . tend to be richer, healthier, better educated, better governed, more respectful of their women, and more likely to engage in trade.”

How did these societies become more peaceable? In various ways. Among the key drivers were

the Age of Reason and the European Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries. [These societies] saw the first organized movements to abolish socially sanctioned forms of violence like despotism, slavery, dueling, judicial torture, superstitious killing, sadistic punishment, and cruelty to animals, together with the first stirrings of systematic pacifism. [my emphasis]

As we’ve seen, Western states have aggressively scuttled their Enlightenment past, since it is anathema to their one-world agenda. People resisting this movement in the name of freedom have exploited the power of the technological exponential to counter their offensive, while states and their private-sector allies struggle to silence them.

Conclusion

States are violence incorporated. They’re an existential violation of the nonaggression axiom. Without their badges and guns, states wouldn’t be threatening global destruction. Contrary to popular opinion, we don’t need them.

Let that sink in: States have no place in a civilized society. The good news is despite their grandiose proclamations, they’re on their last legs, about to go down for the count. Let them go.

Will humanity self-destruct and become a dead planet? Only if we allow states to control us. The free market with its built-in incentives will govern our lives as tech development continues to empower us.

Tags: Featured,newsletter