America’s financial system and state are themselves the problems, yet neither system is capable of recognizing this or unwinding their fatal synergies. why do some systems/states emerge from crises stronger while similar systems/states collapse? Put another way: take two very similar political-social-economic systems/nation-states and two very similar crises, and why does one system not just survive but emerge better adapted while the other system/state fails? The answer lies in what author Geoffrey Parker termed Fatal Synergies and Benign Synergies in his book Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. Synergy results from “interactions that produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects.” In other

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The answer lies in what author Geoffrey Parker termed Fatal Synergies and Benign Synergies in his book Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. Synergy results from “interactions that produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects.” In other words, 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 = 8 is linear, while synergy is 2 X 2 X 2 X 2 = 16.

Given that the core function of states is the distribution of resources, capital and agency, we can distill the difference between Fatal Synergies and Benign Synergies into two questions:

1. What problems cannot be resolved by the financial system/state, no matter how many reforms are thrown at them?

2. Which groups have a meaningful voice in decision-making / governance and which groups are effectively voiceless / powerless?

The first question identifies the structural weak points in the system. These weak points could have any number of sources: they could be perverse incentives embedded in the system, elites caught up in their own enrichment, or even a willful blindness to the nature of the crisis threatening the system.

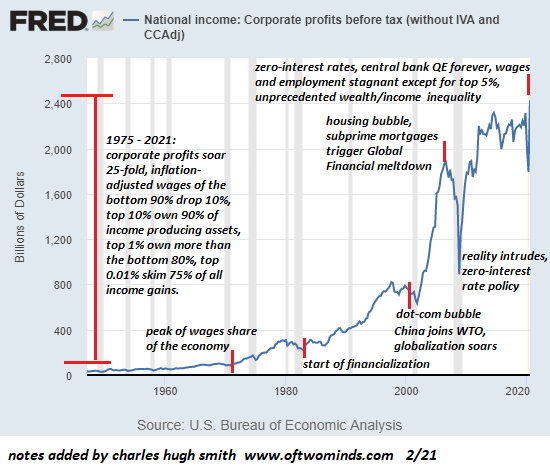

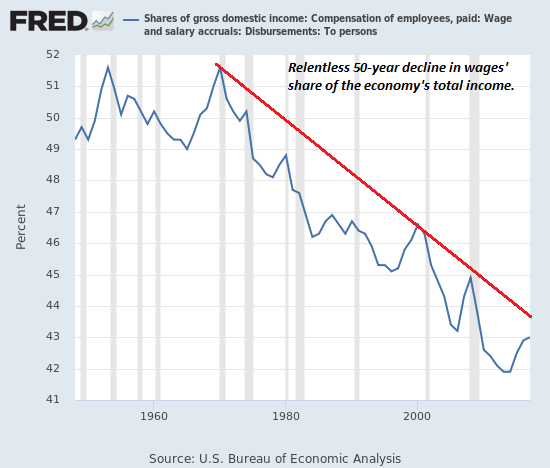

Here’s an example in the U.S. system: corporations reap $2.4 trillion in profits annually, roughly 15% of the nation’s entire output. Politicians need millions of dollars in campaign contributions to win elections. Those seeking political influence have not just billions but tens of billions. Those needing to distribute political favors will do so for mere millions.

Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens: “I’d say that contrary to what decades of political science research might lead you to believe, ordinary citizens have virtually no influence over what their government does in the United States. And economic elites and interest groups, especially those representing business, have a substantial degree of influence. Government policy-making over the last few decades reflects the preferences of those groups — of economic elites and of organized interests.”

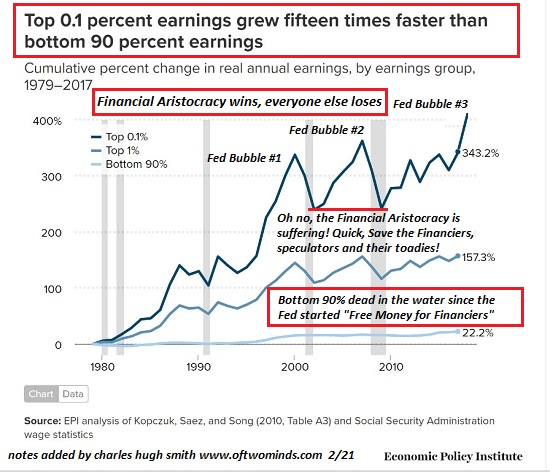

This asymmetry cannot be overcome. Indeed, the past 40 years have witnessed an increasing concentration of wealth and power in corporations and their lobbyists and a decline of political influence of the masses to near-zero. Every reform has failed to slow this momentum, which is constructed of incentives to maximize profits, gain political favors and win elections.

In a similar fashion, the Imperial Presidency has gained power at the expense of Congress for decades–a reality that scholars bemoan but the reforms allowed by the system are unable to stop. So we have endless wars of choice without a declaration of war by Congress, one of the core powers of the elected body.

In a similar fashion, the Imperial Presidency has gained power at the expense of Congress for decades–a reality that scholars bemoan but the reforms allowed by the system are unable to stop. So we have endless wars of choice without a declaration of war by Congress, one of the core powers of the elected body.

An analogy to these systemic weak points is the synergies of an organism’s essential organs: if any one organ fails, the organism dies even though the other organs are working just fine. In other words, any system is only as robust as its weakest essential component/process.

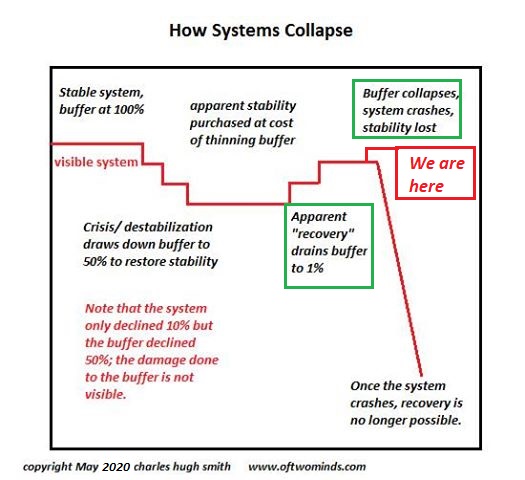

Whatever problems the system is incapable of resolving have the potential to bring down the system once they interact synergistically.

The second question identifies how many groups have been suppressed, silenced or ignored by those at the top of the heap. If these groups have an essential role in the system as producers, consumers and taxpayers, their demand to have a say in decisions that directly affect them is natural.

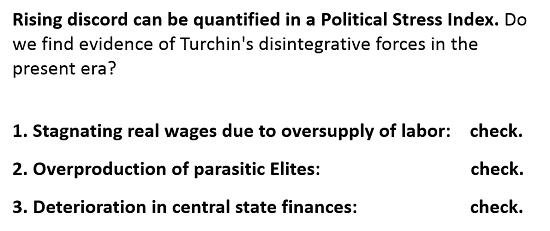

Another group with understandable frustrations at being left out of the decision-making are those in the educated upper classes whose expectations of roles in the top tier were encouraged by their families, society and training. When these expectations are not met because there are no longer enough slots in the top tier for the rapidly proliferating upper classes, the group left out in the cold has the time, education and motivation to demand a voice.

In other words, those denied access to resources, capital and agency who felt entitled to this access will not be as easily silenced as those who accept their low status and restricted access to resources, capital and agency as “the natural order of things.”

All the groups that are denied a voice and access to resources, capital and agency are in effect a sealed pressure cooker atop a flame. The pressure builds and builds without any apparent consequence until it explodes.

The more that power is concentrated in the hands of the few, the greater the desperation of the groups who are locked out of power. As their desperation rises, some of these groups are willing to go to whatever lengths are necessary to effect change.

The process of explosive demands for change erupting is difficult to manage once released. The system’s essential subsystems may be destabilized–the equivalent of organ failure–and once destabilized, it’s often no longer possible to restore the previous stability.

In this environment, the common good falls by the wayside and the system collapses.

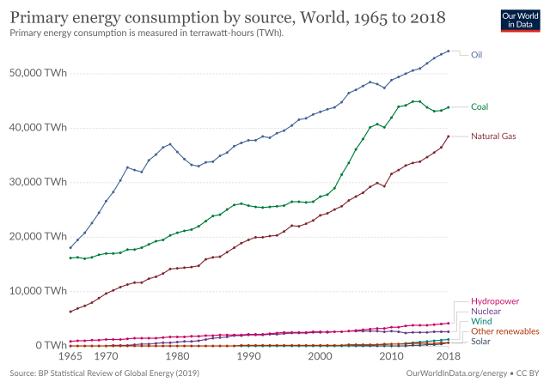

In the context I’ve laid out, Fatal Synergies arise when access to resources, capital and agency are limited by elite hoarding or massive declines in available resources and capital.

Beneficial Synergies arise when whatever resources and capital are available are shared, if not equitably, at least in a process in which every group affected by the distribution has a voice in public decision-making.

Fatal Synergies arise when the identity of each group is based not on shared values and cooperation but on unyielding resistance to competing claims on the nation’s wealth and income.

Beneficial Synergies arise when all groups have a voice and a say in the process of distribution, even if it is limited.

Crises reveal the problems the system is incapable of resolving. How we respond to those constraints and weak points is the difference between Fatal Synergies and collapse and Beneficial Synergies that generate successful evolutionary responses to pressing selective pressures: simply put, “adapt or die.”

America’s financial system and state are themselves the problems, yet neither system is capable of recognizing this or unwinding their fatal synergies.

Tags: Featured,newsletter