Historic Misjudgments in Hindsight Viewing the past through the lens of history is unfair to the participants. Missteps are too obvious. Failures are too abundant. Vanities are too absurd. The benefit of hindsight often renders the participants mere imbeciles on parade. The moment Custer realized things were not going exactly as planned. PT Was George Armstrong Custer really just an arrogant Lieutenant Colonel who led his men to massacre at Little Bighorn? Maybe. Especially when Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and numbers estimated to be over ten times his cavalry appeared across the river. Were George Donner and his brother Jacob naïve fools when they led their traveling party into the Sierra Nevada in late fall? Perhaps. Particularly when they resorted to munching

Topics:

MN Gordon considers the following as important: 6b.) Acting Man, 6b) Austrian Economics, 7) Markets, Featured, newsletter, On Economy, On Politics

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Historic Misjudgments in HindsightViewing the past through the lens of history is unfair to the participants. Missteps are too obvious. Failures are too abundant. Vanities are too absurd. The benefit of hindsight often renders the participants mere imbeciles on parade. |

|

| Was George Armstrong Custer really just an arrogant Lieutenant Colonel who led his men to massacre at Little Bighorn? Maybe. Especially when Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and numbers estimated to be over ten times his cavalry appeared across the river.

Were George Donner and his brother Jacob naïve fools when they led their traveling party into the Sierra Nevada in late fall? Perhaps. Particularly when they resorted to munching on each other to survive the relentless blizzard. Certainly, Custer and the Donner brothers were doing the best they could with the information available to them. The decisions they made must have seemed reasoned and calculated at the time. But what they couldn’t see – until it was too late to turn back – was that with each decision, they unwittingly took another step closer to their ultimate demise. Still they were human just like we are human… no smarter, no dumber. We are not here to ridicule them; but rather, to learn from them. |

|

A Good Man in a Bad TradeRudolf von Havenstein had been president of the Reichsbank – the German central bank – since 1908. He knew the workings of central bank debt issuance better than anyone. He was good at it. Thus, when he was called upon by history to deliver a miracle for the Deutches Reich in the aftermath of WWI, he knew exactly what to do. He would deliver monetary stimulus. In fact, he had already been at it for several years. On August 4, 1914, at the start of the war, the gold mark – or gold-backed Reichmark – became the unbacked paper mark. With gold out of the picture, the money supply could be expanded to meet the endless demands of war. To this end, von Havenstein took public debt from 5.2 billion marks in 1914 to 105.3 billion marks in 1918. Over this time, he increased the quantity of marks from 5.9 billion to 32.9 billion. German wholesale prices rose 115 percent. By the war’s end, Germany’s economy was in shambles. Industrial production in 1920 had slipped to just 61 percent of the level seen in 1913. With a weak economy, and under the crushing weight of debt, it was time for von Havenstein to really get to work. In truth, he didn’t have much of a choice. The limits of fiscal and monetary prudence had been crossed when the gold-mark was replaced with the paper-mark. Reversing course now would have brought an immediate economic collapse and societal discord. What happened next? |

German Reichsbank president Rudolf von Havenstein. The things he didn’t see coming eventually filled entire libraries. [PT] |

The Triumph of MadnessOur friend Bill Bonner, as recently revealed in his Daily Diary, will tell you what happened next:

|

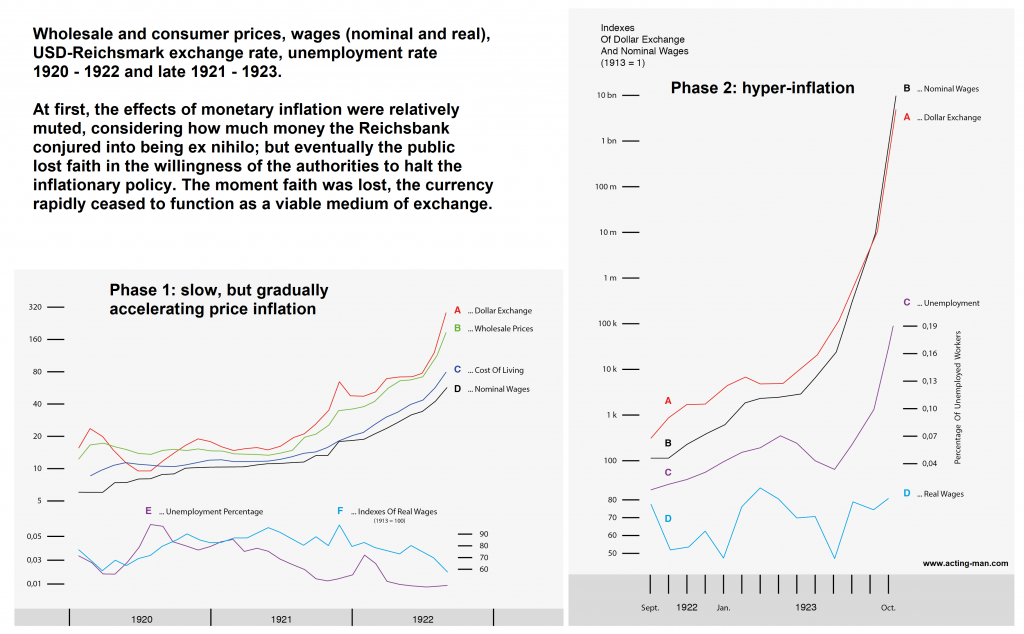

Wholesale and consumer pricesThe evolution of prices, exchange rates, wages and unemployment during the Weimar Republic’s hyperinflation episode (adapted from Constantino Bresciani-Turroni). Initially, the ill effects of the Reichsbank’s money supply inflation seemed to be limited; as real wages declined, unemployment actually fell to record lows – a crack-up boom was underway. Eventually the German government introduced mandatory wage indexing in order to mitigate the growing plight of wage earners. Upon this unemployment immediately soared, moving from record lows to record highs within just two years. At the same time the decline in the paper-mark’s purchasing power and external value accelerated until the currency for all practical purposes ceased to function as a viable medium of exchange. The medium-term political repercussions of this economic catastrophe would soon engulf the whole world. [PT] |

Naturally, no one could have seen that coming. Not even a practitioner of abstract thinking could have forecast such madness. But step by step, madness triumphed – and step by step, madness triumphs today. By this, here is a quick, incomplete list of steps taken into our current madness:

What happens next? Debts will be paid in full. The dollar will go up in smoke. And step by step, madness of the kind only abstract thinking can forecast will triumph. |

A 100 trillion marks banknote issued in February 1924 (note: the German term for “trillion” is Billionen). In order to restore economic confidence, the Reichsbank replaced the paper-mark in mid November 1923 with a transitional currency, the so-called “Rentenmark”, at a rate of 1 Rentenmark for 1 trillion paper marks. It was yet another fiat currency, pretend-backed by agricultural and business real estate, but the limit placed on its issuance did do the trick. For a while all three German currencies (paper mark, gold mark and Rentenmark) existed side-by-side; in August 1924 the Rentenmark was exchanged 1:1 for the new Reichsmark and the old paper mark was phased out. [PT] |

Charts by acting-man/Bresciani-Turroni

Chart annotations and image captions by PT

Tags: Featured,newsletter,On Economy,On Politics