By Bryan Cutsinger Why did the United States abandon the gold standard? In an article published recently by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Maria Hasenstab cites the international gold shortage during the Great Depression. “Countries around the world basically ran out of supply and were forced off the gold standard,” she writes. In passing, the article mentions the American people were not forced off by an international gold shortage, instead by President Roosevelt, who required all but a small amount of gold coin, bullion, and certificates be handed over to the Federal Reserve at .67 per troy ounce. What the article doesn’t mention is the messy details of confiscating gold: refusing to comply faced fines of up to ,000

Topics:

Sound Money Defense League News considers the following as important: 6a.) Gold Standard, 6a) Gold & Monetary Metals, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

By Bryan Cutsinger

Why did the United States abandon the gold standard?

In an article published recently by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Maria Hasenstab cites the international gold shortage during the Great Depression. “Countries around the world basically ran out of supply and were forced off the gold standard,” she writes.

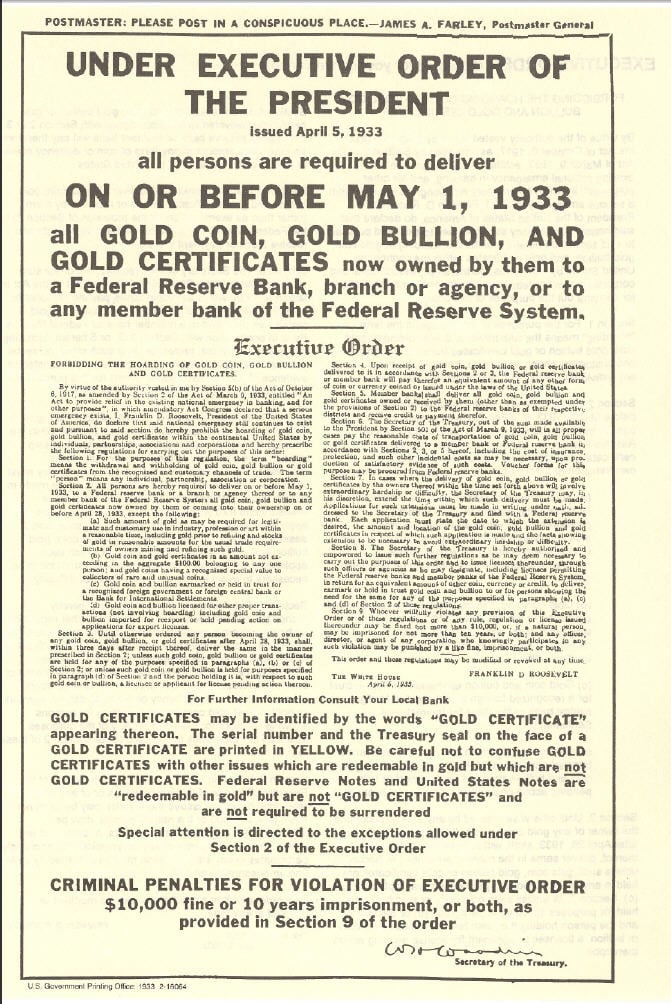

In passing, the article mentions the American people were not forced off by an international gold shortage, instead by President Roosevelt, who required all but a small amount of gold coin, bullion, and certificates be handed over to the Federal Reserve at $20.67 per troy ounce.

What the article doesn’t mention is the messy details of confiscating gold: refusing to comply faced fines of up to $10,000 (almost $240,000 today) and up to ten years in prison.

Then, in 1971, President Nixon sealed the deal by suspending gold redemptions for foreign governments as well. Although Nixon described the suspension as a temporary measure, redemption was never restored, and the dollar lost its link to gold.

Many think severing the dollar’s tie to gold was an obvious improvement. The usual refrain is that the gold standard was deficient in one way or another and that the Federal Reserve has overcome these deficiencies by managing the fiat dollar.

Hasenstab lists three “significant problems” with tying the money to gold:

- The gold standard doesn’t guarantee financial or economic stability.

- It’s costly and environmentally damaging to mine.

- The supply of gold is not fixed.

Let’s consider each in turn.

Supposed Disadvantage 1: The gold standard doesn’t guarantee financial or economic stability.

The gold standard doesn’t guarantee financial or economic stability. But that’s hardly unique. Modern fiat systems have also failed to guarantee financial and economic stability. Given that both the gold standard and our modern fiat system have fallen short in this regard, the relevant question is which of these systems performs better. If a central bank-managed fiat system offers all the benefits of the gold standard while avoiding its drawbacks, there should be ample evidence of improved financial and economic stability under the Fed’s management. Empirical evidence comparing these two periods in US history does not indicate a clear improvement.

Moreover, much of the financial instability observed in the United States during the gold standard period cannot be attributed to the gold standard. Banking panics were much less common in Canada, which was also on the gold standard during this period. This difference stemmed from each country’s distinct approach to banking regulation.

An ideally-managed fiat system can certainly do a better job of promoting financial or economic stability than a gold standard can. In practice, however, governments have frequently mismanaged their fiat monies, with disastrous consequences for the financial sector and the economy as a whole. For example, every episode of hyperinflation throughout history has happened under a poorly managed fiat system.

In short, the historical evidence suggests that fiat money is neither necessary nor sufficient to guarantee financial and economic stability.

Supposed Disadvantage 2: It’s costly and environmentally damaging to mine.

It is true that gold mining is expensive and can harm the environment. But, again, this is not unique to a gold standard. Many productive activities are costly, and some can harm the environment as well. That doesn’t mean these activities aren’t worth doing.

The relevant question is whether switching from the gold standard to a fiat system reduced the resource costs of money and any corresponding environmental damage. The answer is by no means obvious. While the costs to the government of producing fiat money are low, the cost of fiat money to society can be quite large if central banks fail to deliver price stability – a point that Milton Friedman made nearly forty years ago.

Friedman noted that the rapid and unpredictable rise in the price level that occurred after the end of the Bretton Woods system gave rise to a cottage industry of financial advisors selling advice aimed at dealing with inflation–an industry that continues to exist today. These efforts, Friedman noted, have real costs, as resources must be reallocated away from other productive activities. Just how large these costs are is difficult to know, but they are certainly greater than zero.

Another factor to consider is whether abandoning the gold standard reduced the demand for monetary gold. The resource cost advantage that fiat money has over gold stems from the fact that, under a fiat standard, there should be little-to-no demand for monetary gold, thus avoiding the need to mine gold for monetary purposes. But the evidence suggests that demand for monetary gold has risen since we decoupled the dollar from gold, likely due to gold’s use as an inflation hedge. In short, we are likely incurring larger resource costs related to gold mining under fiat money than we would have if we had remained on the gold standard.

Finally, since inflation has been higher under fiat money, we need to consider the cost inflation itself imposes on society by increasing the cost of holding money. When people hold fewer money balances, they incur other costs, including brokerage fees associated with converting financial assets like stocks and bonds into money. A relatively recent study found that at an inflation rate of just 2 percent, these costs amount to 0.04 percent of real (inflation-adjusted) GDP. Interestingly, this figure slightly exceeds my own estimates of the average annual cost the US would incur acquiring monetary gold if we returned to the gold standard.

There are still other factors we could consider when it comes to the resource costs of producing money, but the point is that while fiat money may be cheaper in theory than a gold standard, in practice, it may not be if central banks fail to deliver long-run price stability. Thus, the case for fiat money on this margin is not as clear as the Fed’s article suggests.

Supposed Disadvantage 3: The supply of gold is not fixed.

Finally, while it’s true that the supply of gold is not fixed, neither is the supply of fiat money. Indeed, there is virtually no limit to the amount of fiat money central banks can create, as evidenced by the numerous episodes of high inflation and hyperinflation experienced under fiat standards.

But let’s set this point aside to ask a more fundamental question: Do we want a fixed supply of money? Consider a scenario where there is a sudden rise in the demand for money. If the supply of money is fixed, then the increased demand can only be met by a fall in the price level. If wages and prices aren’t perfectly flexible, however, a falling price level may trigger a recession. Increasing the money supply in such a case could prevent a recession.

More generally, we might want the money supply to expand and contract as needed to meet the demand to hold it. A monetary system with this property would tend to stabilize the purchasing power of money over time, making it less risky to enter into long-term nominal contracts. Indeed, that’s precisely what the gold standard did.

When the demand for money increased, pushing the purchasing power of money up, gold miners increased production to profit from the higher value of gold. As more gold flowed to the mint, the purchasing power of money eventually returned to normal, eliminating the profit opportunity. Likewise, when the demand for money decreased, gold miners reduced production, until the purchasing power of money recovered. Hence, the variable supply of gold generally served to stabilize the purchasing power of money on the gold standard.

Central Banks May Still Be Worse

It is easy to understand why many economists believe a fiat system is superior to the gold standard. A central bank could manage the supply of fiat money in a way that mimics the supply mechanism of a gold standard, without the resource cost of mining gold. And, since a fiat system doesn’t require digging up gold, its supply might also respond to demand shocks more rapidly. Such a system would not only outperform the gold standard — it would do so at a lower cost.

But there is one important difference between a fiat system and the gold standard: the supply of money on the gold standard is governed by an automatic mechanism, whereas the supply money on a fiat system is governed by the central bank. Although a central bank can do a better job, it might not. More often than not, central banks have performed much worse.

Originally Published on AIER's The Daily Economy.

Tags: Featured,newsletter