There is no way authorities can limit the coronavirus and restore global growth and debt expansion to December 2019 levels. Authorities around the world are between a rock and a hard place: they need policies that both limit the spread of the coronavirus and allow their economies to “open for business.” The two demands are inherently incompatible, and so neither one can be fulfilled. The problem is the intrinsic natures of the virus and the global economy. This virus is highly contagious during its asymptomatic phase, which is long (5 to 20 days), and therefore impossible to control with the conventional tools of identifying people with symptoms and isolating them, and tracking their contacts with others. While there is much we do not know for certainty about

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5) Global Macro, 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Eamonn Sheridan writes CHF traders note – Two Swiss National Bank speakers due Thursday, November 21

Charles Hugh Smith writes How Do We Fix the Collapse of Quality?

Marc Chandler writes Sterling and Gilts Pressed Lower by Firmer CPI

Michael Lebowitz writes Trump Tariffs Are Inflationary Claim The Experts

There is no way authorities can limit the coronavirus and restore global growth and debt expansion to December 2019 levels.

There is no way authorities can limit the coronavirus and restore global growth and debt expansion to December 2019 levels.

Authorities around the world are between a rock and a hard place: they need policies that both limit the spread of the coronavirus and allow their economies to “open for business.” The two demands are inherently incompatible, and so neither one can be fulfilled.

The problem is the intrinsic natures of the virus and the global economy. This virus is highly contagious during its asymptomatic phase, which is long (5 to 20 days), and therefore impossible to control with the conventional tools of identifying people with symptoms and isolating them, and tracking their contacts with others.

While there is much we do not know for certainty about Covid-19, what’s clear (and not well-reported) is that its lethality is not exactly like a normal flu. The number of otherwise healthy people under the age of 60 who die of a regular flu is near-zero. The number of otherwise healthy people under the age of 60 who die of Covid-19 is not large as a percentage of cases but it is worryingly above zero. A great many otherwise healthy people under the age of 60 have died of Covid-19.

Yes, the vast majority of those who die are elderly and suffering from chronic health issues, but the number of younger, healthier people who are dying makes this virus consequentially different from a typical flu.

Everyone looking at total deaths (currently much lower than the fatalities in a typical flu season) is missing the semi-random lethality of Covid-19 in younger, healthier people, or at least certain strains of the virus in certain conditions (air pollution, viral load, etc.) and in not yet fully understood sub-populations.

This uncertainty and semi-randomness means authorities cannot claim that Covid-19 is “no worse than a regular flu” because the number of 40-year old doctors, nurses, transit employees, etc. who die of regular flu is near-zero, but the number who are dying of Covid-19 is far above zero.

In a regular flu season, people with healthy immune systems have little fear of dying of the flu. But Covid-19 is killing enough otherwise healthy people that there cannot be absolute certainty that the risk of death is essentially zero. This is an enormous difference psychologically, a difference that is currently under-appreciated.

The global economy is much like a shark: it must keep moving forward in growth and debt expansion or it dies. This reality is poorly understood and therefore of paramount importance.

The difference is debt. A large percentage of global consumption is ultimately based on debt. Debt masks a variety of inefficiencies, but the drag of inefficiencies and unproductive profiteering is visible if we look at the rate of “growth” and the rate of “debt expansion.”

In the past 12 years, debt has exploded higher globally just to maintain weak growth. Where $1 in new debt once increased GDP by 50 cents, now it boosts GDP by 5 cents–or by some measures, zero. It’s taking more and more debt to keep the “growth” shark moving forward.

The problem is debt must be serviced: interest must be paid and principal paid down. Even at near-zero interest rates, the principal payments loom large.

Debt has a built-in opportunity cost. Once the borrower takes on more debt, a chunk of income must be allotted to paying the new debt. That income is no longer available to be saved or invested or spent on goods and services; it’s tied up for the life of the loan.

Eventually, borrowers’ income is completely consumed by debt service and paying essentials such as rent and food. There is no income left after essentials and debt service are paid.

So what happens when income falls? There is no longer enough income to pay all the expenses, and so what does the household or company do? It pays the essential bills and defaults on the debt, i.e. stops servicing the debt.

The lender can pursue legal action to collect the debt, but heavily indebted households and companies simply don’t have the income or assets to pay the loan back. They declare bankruptcy and all their lenders must eat the loss.

This has far-reaching consequences. Lenders saddled with huge losses due to mass defaults are insolvent, and must conserve earnings to rebuild their capital requirements. To stem the flood of losses, they have to tighten lending standards and avoid making loans to over-indebted households and companies.

But reducing their lending to marginal borrowers greatly reduces their income, as marginal borrowers must pay higher interest rates, and so these are the most profitable loans lenders can make.

You see the feedback loop here: less lending, less profits, and lenders’ losses pile up. The banking sector unravels.

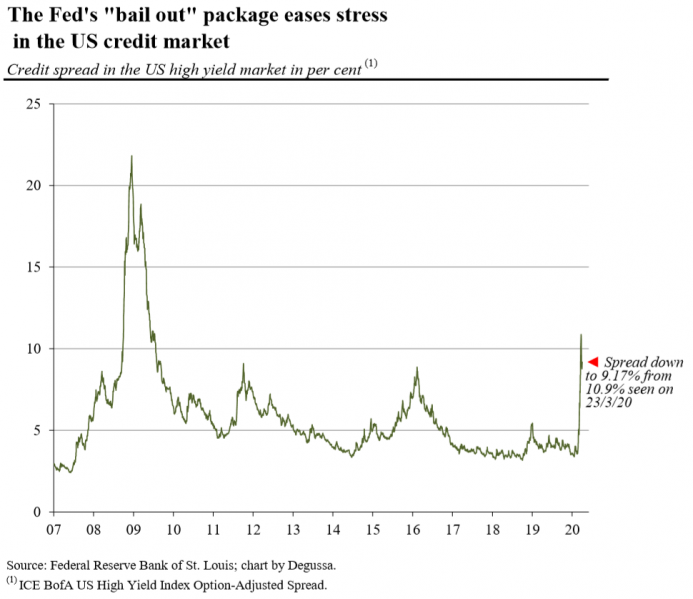

As in 2008, we see central banks bailing out insolvent lenders, but as I explained in a recent blog post, bailouts are not the same as revenues. Bailing out lenders and over-indebted corporations doesn’t magically create new creditworthy borrowers. Buy The Tumor, Sell the News (April 10, 2020)

Bailouts are short-term emergency measures, but they don’t restore the foundations of sustainable debt: credit-worthy borrowers.

From the point of view of the potential borrower, why borrow more money to spend on a superfluous vacation if income is uncertain? Why buy a house if there’s a chance it might decline in value by 20%? Wouldn’t it be wiser to delay purchases funded by more debt? Of course it’s wiser.

Let’s add up the uncertainties:

1. Covid-19 is not as risk-free for healthy people as ordinary flu. Therefore there is an uncertainty that favors caution and prudence and risk avoidance.

2. From the point of view of potential borrowers, there is also uncertainty about future income and asset values, and so lowering risk makes sense. The easiest way to avoid risk is not take on new debts to fund discretionary purchases and save money to create a cushion against uncertainties.

3. From the point of view of lenders, there is uncertainty about the creditworthiness of borrowers, households and companies alike. The past is not a good guide to the future: households with sterling credit may default if a primary wage earner loses their job.

Charging marginal borrowers higher interest rates is no longer a low-risk strategy, as what good is a month or two of higher interest if the borrower defaults and the lender is stuck with an enormous loss?

These uncertainties cannot be dialed back to zero. To truly limit the spread and semi-random lethality of Covid-19, authorities will have to make extreme measures permanent–for example, mass testing of the populace on a scale never seen, plus identifying those at lower risk (those who have recovered, etc.) and those at higher risk (elderly people with multiple health issues) and imposing different rules of conduct on each group.

Economically, the global financial system will unravel if debt expansion ceases or reverses, and incomes decline or even become uncertain.

Recall that the absolute number of defaults does not have to rise by much to sink the system. Even if there are no additional defaults, once debt stops expanding, the system unravels, as it requires expanding debt to fund expanding consumption (“growth”) and the continuing purchase of assets at bubble-top high valuations.

Once assets decline in market value, the system unravels, as bubble-top valued assets are the collateral holding up the world’s mountain of debt. Once the collateral shrinks, the system becomes increasingly prone to a self-reinforcing collapse of lending and asset crashes, as sellers can’t find any buyers and lenders can’t find any creditworthy borrowers with solid collateral and income.

For an example, consider global tourism and travel, including business-related travel. This sector accounts for roughly 10% of global GDP ($9.25 trillion). Tourism worldwide – Statistics & Facts. In 1960, about 25 million people traveled internationally. In 2019, the number of international travelers was 1.4 billion. This is a 56-fold increase.

When I moved to Hawaii as a young teen in 1969, the state had just cracked the 1 million visitors per year line. In 2019, 10.4 million visitors came to Hawaii.

Tourism and even business travel are the epitome of discretionary spending. What happens to incomes, asset valuations, collateral and debt defaults if global tourism only recovers to 50% of 2019 levels?

That would reduce global GDP by 5%, but this drop will trigger financial consequences many multiples of 5%.

What happens to the pricey room rental rates that have become standard? What happens to the incomes of AirBnB hosts? How many will seek to sell their properties or default on their mortgages?

What happens to property values in cities dependent on tourism when a significant percentage of AirBnB owners try to sell their properties? Who will want to take the risk of buying a property which could lose much of its value going forward?

Another apt analogy for the global financial system is an airliner. Airliners are optimized for flying at high altitudes at speeds of between 500 and 575 miles per hour. This is their envelope of maximum fuel efficiency.

While an airliner is physically able to fly at 500 feet, its fuel efficiency will be greatly reduced. Just as airliners cannot fly above a maximum altitude (around 45,000 feet) or approach the speed of sound (Mach 1), they cannot reach their maximum range flying at 500 feet.

The airliner is optimized for a very narrow envelope, and once it leaves that envelope, bad things happen: its engines flame out, it runs out of fuel, etc.

The global economy is optimized for a vast, steady expansion of debt to fund an equally vast and steady increase in consumption. Once it slips out of this narrow envelope, it crashes.

Central banks and governments can mask this in the short-term by substituting bailouts for revenues, but bailouts are not sustainable replacements for revenues, incomes, profits and debt service. The global economy has already fallen out of its sustainable envelope, and the only questions are its rate of descent and how long the remaining fuel will last.

There is no way authorities can limit the coronavirus and restore global growth and debt expansion to December 2019 levels. This is not what people want to hear, but it’s the reality we will have to deal with.

Tags: Featured,newsletter