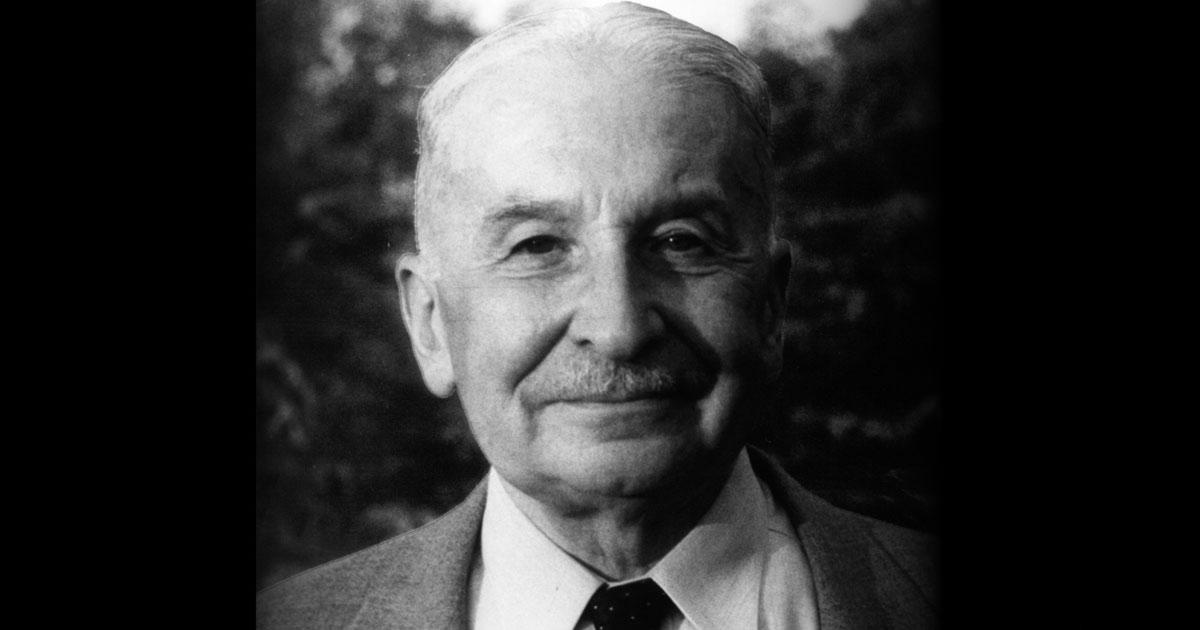

Ludwig von Mises published Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen über den Sozialismus in 1922 (translated into English as Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, 1951). In more than five hundred pages, the most prominent representative of the Austrian school offers a comprehensive and deep analysis of the “socialist phenomenon.” Despite the catastrophes associated with the attempt to install a socialist system, this ideology has lost little of its appeal. Modern civilization is still threatened by socialist thinking and the resulting policies. As Mises thoughtfully explains, Marxism first poisons the mind of the people, then seizes politics, and finally appears as a destructive power of domination. It is important to understand the spiritual foundations

Topics:

Antony P. Mueller considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Ludwig von Mises published Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen über den Sozialismus in 1922 (translated into English as Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, 1951). In more than five hundred pages, the most prominent representative of the Austrian school offers a comprehensive and deep analysis of the “socialist phenomenon.”

Ludwig von Mises published Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen über den Sozialismus in 1922 (translated into English as Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, 1951). In more than five hundred pages, the most prominent representative of the Austrian school offers a comprehensive and deep analysis of the “socialist phenomenon.”

Despite the catastrophes associated with the attempt to install a socialist system, this ideology has lost little of its appeal. Modern civilization is still threatened by socialist thinking and the resulting policies. As Mises thoughtfully explains, Marxism first poisons the mind of the people, then seizes politics, and finally appears as a destructive power of domination. It is important to understand the spiritual foundations of socialism, and there is no better basis for doing so than “The Socialist Commonwealth,” by Ludwig von Mises.

Why Socialism Triumphs

In the foreword of Die Gemeinwirtschaft (I refer to the second revised edition of 1932; all translations are my own), the socialist ideal seemed to be dismissed by the mid-nineteenth century. Socialist reasoning was exposed, and all practical attempts to realize it had failed. But then Karl Marx (1818–83) created Marxism as an edifice of “anti-logic, anti-science and anti-thought.”

The theories of Karl Marx (1818–83) have been destructive. First, he contradicted the universality of logic, it now being “class-dependent.” Secondly, he turned the dialectical methodology from his philosophical master thinker G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831) “upside down.” The Hegelian “world spirit” no longer determines the dynamics of history. The “substructure,” which Marx conceived as economic-technical development, now does.

Thirdly, Marx’s pretentious claim that his teachings were “scientific” allowed him to state that he detected valid “historical laws” and that these said that social development would inevitably lead to socialism. Karl Marx reinterpreted Hegel’s concept of “the end of history” as the perfection of the earthly world under socialism by means of a socialization of the means of production.

To portray the historical inescapability of socialism as “scientifically proven” fit very well with the zeitgeist of the mid-nineteenth century. “Historical materialism” claimed to be placed on the same level as knowledge in physics and equal to the Darwinian theory of evolution. In the eulogy at the funeral of Karl Marx, his friend and sponsor, Friedrich Engels (1820–95), praised the achievement of the communist ideologue in front of the few other comrades that were present:

Like Darwin discovered the law of the development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto hidden under ideological overgrowth, that before all things human beings must eat, drink, dwell and dress before they are able to practice science, art, religion, etc.; that is to say, the production of the immediate material means of subsistence and thus the current level of economic development of a people in a period of time forms the basis from which the state institutions, the legal views, art and even the religious ideas of the people have developed, and from which they also have to be explained—not the other way around, as has been the case up to now.

According to Friedrich Engels, Marx discovered “the special law of motion of today’s capitalist mode of production and the bourgeois society it produces.” The key to this insight, Engels explains, was the “discovery” of the “surplus value,” as it provided the tool for the “scientific penetration” of the capitalist “laws of motion.”

It is important to understand that Friedrich Engels states that Marx was first and foremost a revolutionary and that science served him as a tool to pursue his revolutionary goals. Engels himself provides the confirmation that Marx’s economic writings can only be properly understood if they are seen as aids to the communist revolution.

According to Engels, Marx was a communist revolutionary who was primarily concerned with “participating in the overthrow of capitalist society and the state institutions it created.” That Marx was indeed not a scientist or scholar in the first place, but above all else, a communist, and that his work must be interpreted from this point of view, was expressed succinctly by Murray Rothbard:

The key to the complicated and massive system of thought created by Karl Marx . . . is basically a simple one: Karl Marx was a communist.

Beyond that, Ludwig von Mises determines that the “unparalleled success of Marxism”

is because it promises the fulfillment of deeply rooted age-old dreams and resentments of mankind. With the claim to scientific validity, Marx promises a paradise on earth, a land of milk and honey full of happiness and enjoyment and, what sounds even sweeter to the badly off, the humiliation of all who are stronger and better than the crowd.

Why Socialism Pervades

A dedicated socialist is foremost a revolutionary politician and is different from other people. Normal persons put their personal relationships above politics and understand themselves mainly as a member of a specific family, profession, or of their religion, region, and nation.

The hard-core socialist, in contrast, is a leftist politician in the first place. He puts politics above anything else. Politics is his abstract god and if he himself cannot become one, powerful other politicians serve as his god. This makes the Left successful in politics and it also makes the leftists dangerous when they come to power—and power is what they are looking for anytime and anywhere, not only in politics but in all areas of society.

The attractiveness of socialism comes from the creed that those who advocate socialist measures consider themselves the friend “of the good, the noble and the moral,” as unselfish champions of necessary change. The Socialist typically identifies himself as a person “who selflessly serves his people and all humanity, but above all as a true and intrepid researcher.” In contrast to this self-view of the socialist, anyone who criticizes socialism with the standards of science is depicted as

an advocate of the evil principle, as a rogue, as a filthy mercenary of the selfish special interests of a class damaging the common good, and as an ignoramus.

To this day, this tenor has changed little.

After the end of the Soviet Union, in 1991, it looked for a while as if the communist ideology had had its days for good. But it did not take long for a new wave of sympathy for socialism to emerge, and it is getting stronger. Nowadays, the enthusiasm for the socialist planned economy does not come with red flags on the streets but is being celebrated in academic seminars and by the social justice movement and comes in all colors, including green.

One must agree with Mises when he states, a hundred years ago, that it has become customary “to talk and write about economic policy matters without having thoroughly thought through the problems that lie in them to the end.” The public discussions of the questions of human society are “mindless” and steer politics along paths “that lead directly to the destruction of all culture.”

Not different from the epoch when Mises was writing his treatise, today as well, so it seems, it is a “hopeless endeavor to convince the passionate supporters of the socialist idea by logical evidence of the perversity and absurdity of their views.” Then as now, the supporters of socialism are not open to any argument “that they do not want to hear and see and, above all, do not want to think about.”

Instead of refuting the adversaries of their ideas with rational argumentation, the Socialists turn to personal attack. In Marx’s tradition, his followers have their opponents

insulted, mocked, ridiculed, suspected, slandered. . . . Their polemics are never directed against the explanations, always against the person of the opponent. Few critics can withstand such assaults and gain the courage to disparage socialism pitilessly the way it would be the duty of a true scientific thinker.

Mises cherishes the hope that new generations will grow up “with an open eye and open mind,” who will “approach things impartially and without prejudice” and who will “dare and test” the socialist claim. Mises hopes for a generation that will begin to think again and who will act with precaution. Mises dedicates his book to these new generations. Through his book, Ludwig von Mises wants to speak to future students, to a generation that is yet to come.

These challenges arise in our time. Socialism still is a mental misconception. Marxist thinking, often unconsciously, pushes the masses toward socialism. As in the days of the publication of Mises’s Socialism, we, too, must admit that we live in the “age of socialism.”

Likewise, today, one asks with Mises:

Where is an influential political party “which may dare to stand frankly and freely for the special ownership of the means of production”? Then, as now, the word “capitalism” is ostracized and used as the “sum of evil.” Socialism is the dominant idea of the time: “Even the opponents of socialism are completely under the spell of its ideas.”

Socialism’s Destructive Power

Even though communism failed to bring prosperity and freedom, socialist thinking continues flourishing as an ideology in academia, education, and the media. Disguised as champions of social justice and equality, the modern socialists demand a planned economy to counter injustice and fight against climate change. Again and again, these movements are gaining enough votes to become part of the government and pursue their destructive plans.

Like the older versions, modern socialism, too, is not what it claims to be. It is not pioneering a better and more beautiful future. On the contrary, it “shatters of what millennia of culture have painstakingly created.” Socialism “does not build, it tears down.”

The destructive policy of socialism consists of the depletion of capital. This process may be hidden for quite some time because

as long as the walls of the factory buildings are still standing, the machines are still running, the trains are still rolling over the rails, it is believed that everything is fine. The growing difficulties in maintaining the high standard of living are attributed to other causes, except for the fact that a policy of capital depletion is pursued.

Most people do not recognize that the capital of the economy must be continuously maintained and restructured. Ongoing capital formation is the path to prosperity and as such, the ownership of the means of production is indispensable for economic and social progress. Socialism, on the other hand, takes the path of destruction because it undercuts the maintenance and the incessant improvement of a nation’s capital structure.

Tags: Featured,newsletter