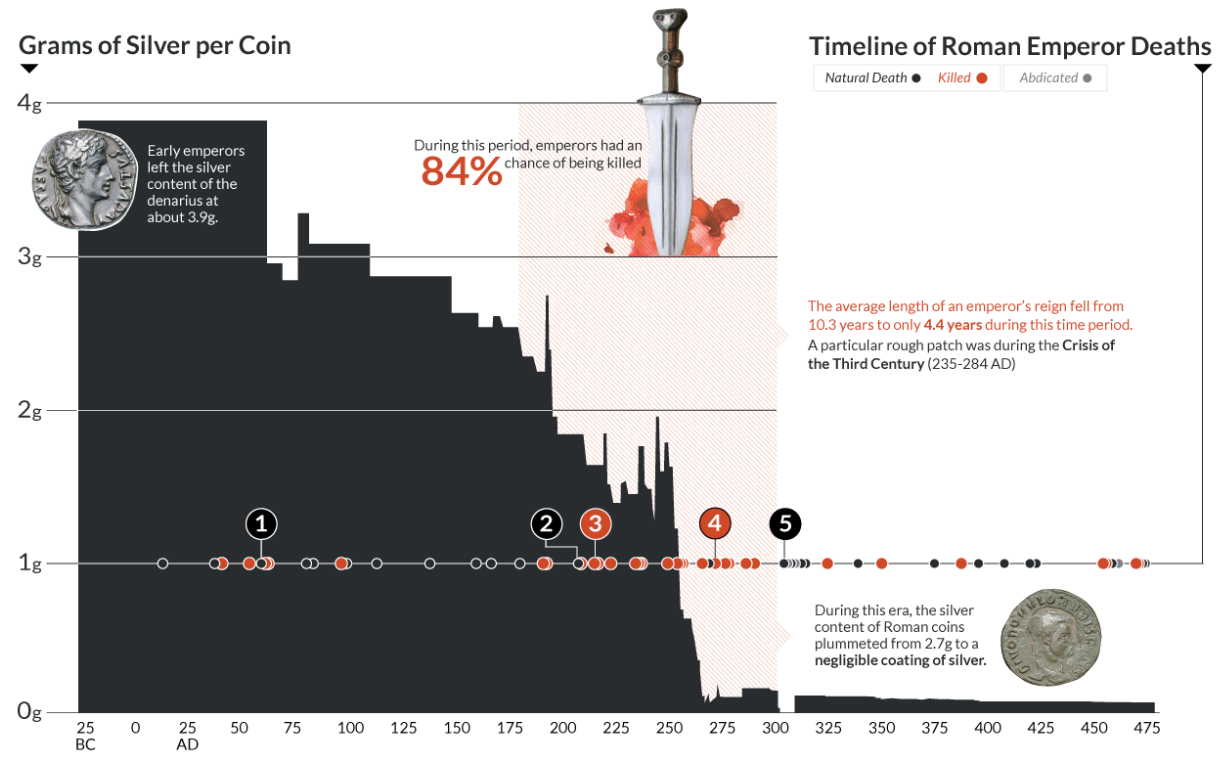

In 301 AD, Roman emperor Diocletian implemented price ceilings on over 1,200 goods. The silver coinage had been debased over the past 250 years, and the citizens were understandably unhappy about high prices. In 50 AD, each denarius had about 3.9 grams of silver, but then the empire debased the coins, sometimes in dramatic steps and sometimes more slowly. By 125 AD, the coins had less than 3 grams of silver. By 200 AD, it was less than 2 grams. There was another precipitous drop in silver content between 250 and 275 AD, and in short order there was only a “neglible coating of silver” on each coin.Image source: Visual Capitalist.The English translation of Diocletian’s edict is fun to read. It shows that not much has changed in politics over the millennia.

Topics:

Jonathan Newman considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

In 301 AD, Roman emperor Diocletian implemented price ceilings on over 1,200 goods. The silver coinage had been debased over the past 250 years, and the citizens were understandably unhappy about high prices. In 50 AD, each denarius had about 3.9 grams of silver, but then the empire debased the coins, sometimes in dramatic steps and sometimes more slowly. By 125 AD, the coins had less than 3 grams of silver. By 200 AD, it was less than 2 grams. There was another precipitous drop in silver content between 250 and 275 AD, and in short order there was only a “neglible coating of silver” on each coin.

Image source: Visual Capitalist.

The English translation of Diocletian’s edict is fun to read. It shows that not much has changed in politics over the millennia. Diocletian is introduced as “dutiful, blessed, unconquered” and the empire’s military victories are acknowledged as having produced a wonderful peace. But, the emperor is obliged to “secure the quiet we have established with the reinforcements Justice deserves.” The barbarian tribes had been vanquished, the Samaritans, Persians, and Britons had been conquered, but now a new war must be waged against greed: “Greed raves and burns and sets no limit on itself.” Greedy businessmen were exploiting the poor with high prices and “It is appropriate to the forethought of us who are the parents of the human race, that justice intervene in matters as a judge.”

Some lines in this edict are reminiscent of the media’s take on Kamala Harris’s anti-price gouging remarks. The edict says that prices increase even when there is an “abundance of goods” and a “bounty of good years.” James K. Galbraith and Isabella Weber made a similar claim in their pro-Harris piece, saying that egg prices increased even when egg production increased. Of course, neither Diocletian nor these 21st century authors said anything about the money. A pro-price control article at The Atlantic says, “Price-gouging laws represent a different set of market rules, grounded in fairness”—Diocletian’s edict similarly appeals to justice, public interest, and righteousness. Even Paul Krugman’s wordplay, in which he tried to claim that a ban on price gouging is not the same thing as a price control, has its 4th century counterpart: “we have taken the position, not that we must set prices of goods and services for sale […] but that we must set a limit.”

Lactantius, a philosopher, wrote about the effects of Diocletian’s edict a few years later:

While Diocletian, that author of ill, and deviser of misery, was ruining all things, he could not withhold his insults, not even against God. This man, by avarice partly, and partly by timid counsels, overturned the Roman empire. […]

He also, when by various extortions he had made all things exceedingly dear, attempted by an ordinance to limit their prices. Then much blood was shed for the veriest trifles; men were afraid to expose aught to sale, and the scarcity became more excessive and grievous than ever, until, in the end, the ordinance, after having proved destructive to multitudes, was from mere necessity abrogated.

Diocletian’s edict is just one instance of price controls. But the historical record shows that these results are universal. In Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls, Schuettinger and Butler survey this “grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure,” as David Meiselman describes the record in the Foreword:

Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages. Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves.

Ryan McMaken and I discussed Harris’s price controls and whether economists are to blame for the public’s ignorance of the effects of price controls on the most recent episode of Radio Rothbard. It’s true that there are bad economists out there who make excuses for terrible policies like price controls, but the overwhelming majority of economists see, understand, and have gone to great lengths to explain the disastrous consequences of price controls. This is why The Atlantic piece I referred to earlier is titled, “Sometimes You Just Have to Ignore the Economists.” If the public and journalists ignore economists and the historical record over millennia, even when economists write a slew of articles like this one every time price controls are proposed by political leaders, then much, if not most, of the blame belongs to the media and the State.

Tags: Featured,newsletter